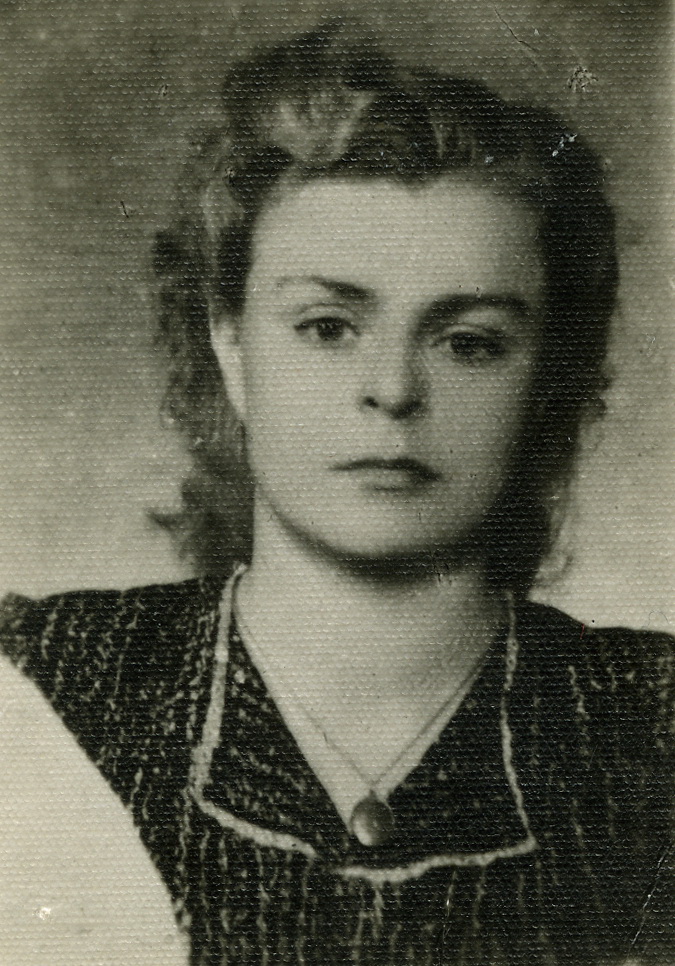

Vytenė Muschick

I was a teenager when Dalia Grinkevičiūtė passed away in 1987. I knew her personally from my summer visits to Laukuva in Lithuania, where she lived at my aunt’s house. I knew her but I didn’t know her true life story and her struggle for survival as a child. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, I got to know the whole truth about her life, and I would like to share this with you today.

Dalia, her brother Juozas, and her parents were deported to Siberia from their hometown of Kaunas during the first mass deportations on 14 June 1941. She was 14 years old at the time and her brother Juozas was 17. That deportation consisted of over 12,000 people; 5,060 of these were children, and 863 more children were later born in exile (Burauskaitė 1999, p. 52). Dalia, her brother, and her mother were separated from their father and taken to the Altai region, where the family worked on a beetroot farm; later, in 1942, without any prior warning, they were transported to the Far North.

The horrors of the deportations are relatively well known today. What I would like to point out in my essay is the wide range of emotions depicted in Dalia Grinkevičiūtė’s testimony – ranging from uncertainty to hope, disappointment and pain – but also the determination to survive.

Destination unknown

The first deportations were unexpected, catching the population unprepared. People departed without warm clothes, without dried bread for a journey of tens of thousands of kilometres. Dalia Grinkevičiūtė describes her journey in detail and it is through the eyes of a child that we come to understand what that long journey involved. From the very beginning, she senses that something bad has happened – that something safe and stable has been broken: “I am aware that a phase of my life has come to an end, a line drawn underneath it. Another is beginning, uncertain and ominous” (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 15). Yet the curious child in her is strangely excited as well. The unknown suggests a journey, an adventure in the making:

The landscape glides slowly past our barge: farms and fields, herds of cattle, sand dunes. Gaggles of children play on the beaches; they swim, they call to us and wave. The sunny days drift along, one after the other. The ‘Nadezhda Krupskaya’ tows our barges towards the mouth of the Lena. Everyone is upbeat. We are fed three times a day and given as much water as we can drink. We bathe frequently and can wash our clothes; we look more youthful, livelier. For the young it is like a field trip. A school holiday. They wear their best clothes, mostly the ones they brought from Lithuania. (…) Here and there couples can be seen chatting and flirting. The sounds of an accordion and singing can be heard from a barge up ahead.

Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 33

However, the “omniscient” narrator immediately clarifies that the northbound journey by barge was just a brief illusion of a life in freedom: “Oh, sunlit days! How often we remembered this time when life became difficult – it was our holiday escape, our journey on the Lena”. (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 35)

Are they heading for America?

Dalia Grinkevičiūtė engages in comments without the filter of subsequent knowledge. She captures interesting facts like someone who does not have the full picture or, in this case, any idea of the final destination of her exile. In the case of Dalia’s family, on the morning of 14 June, they were informed by a soldier of the unspecified duration and location of their exile: “deported for life to the remotest regions of Siberia”.

But as the deportees are transported farther and farther north, American canned goods, American flour sacks, and barrels of butter appear on the barges (in fact, this was the result of the Lend-Lease Act, signed by the US Congress in 1941, whereby America bailed out the USSR in WWII with products and machinery), and suddenly the speculative question arises: “Where are they taking us? Can it really be to America?” (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 33). Cut off from reliable news, deportees cling to hope much like the drowning clutch at straws, and they spread rumours: “A rumour has been going around regarding the Lithuanians who were transported earlier in seasonal ships to Tiksi, an Arctic Ocean harbour, and taken… where? ‘To America, of course’, say ‘the Americans’. Some of the rumours are very specific, like the one about people tossing their work clothes into the sea because they won’t be needing them in America” (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 37).

During the transport, the exiles wait for two weeks in Ust-Kut for steamships, and some of them begin to dream of the supposed promise of imminent freedom: “We spent two weeks here waiting for a steamer. The ‘Moskva’ and the ‘Lermontov’ have already made two round trips. The ‘American territories’ theory appears to be holding. Sceptics are called pessimists, blockheads, killjoys and whiners” (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 31). It is only much later, when Dalia goes to the harbour in Tiksi, that she finds out for herself that there is some truth to the rumours. There were indeed Lithuanians who threw their belongings into the sea when they were transported on seagoing ships because they believed they were going to America. But, in reality, those deportees ended up in the mouth of the Yana River, where many did not survive.

The Reality

The full reckoning with reality awaits Dalia and the other 450 exiles from Lithuania when they reach their destination on 28 August 1942. This is the island of Trofimovsk, at the mouth of the Lena River in the Laptev Sea. Dressed in summer clothes, they arrive on an uninhabited island where the ten-month-long polar winter is about to set in. Dalia’s first encounter with the island is its steep and crumbling river bank:

I watch more barges being manoeuvred towards the shore. So this is ‘America’, I think. A bitter wind is blowing in from the mouth of the Lena river, which is white with foam. (…) I look around and I am chilled to the bone. Far and wide, tundra and more tundra, naked tundra, naked tundra, not a sprig of vegetation, just moss as far as the eye can see. In the distance, I notice something that looks like a small hill of crosses. We learn that these are the graves of the Finns. Two weeks ago, they were brought in from Leningrad already debilitated as a result of the blockade, starved, and suffering from typhus, and now they are dying. Suddenly, I’m gripped by fear.

Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 39, 41

All illusions immediately disappear. The new exiles – mostly women with children and elderly people – arrive unprepared for the polar winter. They need to build a shelter, which they hurriedly make out of moss and bricks with their own hands before the winter blizzards come. They are completely at the mercy of their supervisor, Sventickis, who does not miss an opportunity to mock them. Dalia reflects on the humiliation she has already experienced for the first time in the Altai region. She realises that the first step in breaking and ‘de-personalising’ someone is to call her by a number rather than by her name, and she points out the effect of this. She feels like a thing (object) rather than a person (subject). Dalia remembers the injustice that she experienced working on the beetroot farm at the age of fourteen. She felt what it was like to be treated primarily as cheap labour.

The nineteenth and twentieth wagons (with fifty deportees in all) are bound for the collective farm. Whenever the roll call was taken on the train, I found it unsettling to be addressed as a number. I feel the same discomfort now when the Chekist, a guard from the secret police, shouts, ‘Number seventeen! Number seventeen?’. It takes several minutes to register, then I feel the blood rush to my face, my heart pounding. Number seventeen from wagon nineteen – that is who I am! I’m glad Dad isn’t with us to hear it. It’s like being in chains. Each of us is called in turn. The swarthy Chekist with the steely eyes gives me a look that feels worse than a blow. It is the look of a slave merchant, assessing my muscles, calculating the amount of work that he can squeeze out of me. For the first time in my life, I feel like an object. No one seems to care that I’m not in school, studying as I should be. I harbour the slave’s terrible hatred and resentment. Turning my head, I notice Mother. She is standing a short distance away, watching with an expression of pain.

Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 19–20

Child labour

Everything, both the deportees’ lives and labour, was organised by their supervisor, Sventickis. If you don’t work, you don’t get food rations, which means you starve. What kind of work does Dalia, a 15-year-old teenager, do? First of all, she has to stack bricks for the construction of housing barracks. While the men working together carry 12 to 15 bricks each, she can only manage to carry seven. She ties the bricks together with a rope and drags them up:The work goes something like this: three metres up a steep ladder from the cargo hold, then across the deck to a gangplank and down the gangplank to the shore. Overall gradient: ten metres.

A thousand bricks will earn her 80 roubles. Dalia is proud that after 12 hours of hard work, she has stacked 250 bricks and earned her family 20 roubles. Her next job is that of a builder. Although she begins with adolescent enthusiasm and pride, saying that she feels a sense of moral satisfaction because she will be living in a house that she built with her own hands, her ‘house’ is nothing more than alternating layers of bricks and moss… The moss is gathered from the tundra nearby; inside this barrack, the rooms are 8 m wide and 25 m long, and the people who live in them do so in the same groupings in which they were transported in the wagons. They sleep on bunks, 50 cm per person. Dalia’s barrack consists of twenty such ‘rooms’. Dalia is then assigned to haul logs from the river. When the last barge arrives with American goods, she is told to carry sacks of flour. The overseer mocks the emaciated exile child: A flour sack is also placed on my back. (…) I realize I’m swaying. When I come to, I’m lying on the deck. The sack of flour has dislocated my shoulder as it fell. ‘How old are you?’ – ‘Fifteen’ – ‘Fifteen! And you can’t lift a sack of flour? We have twelve-year-olds who can load ships. The masses have gone soft’. – The supervisor orders me to carry boxes of tins instead (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 46).

Dalia’s next job in Trofimovsk, with the polar winter already in full swing, is to haul logs. The rates and the nature of the work are set by Sventickis:

Sventickis sets the salary for our slave labour, which is delivered at the cost of our blood and our lives. His valuation: between one and three rubles per day. For three rubles we haul logs all day. Two rubles is his assessment of a twenty-kilometre journey across snowdrifts with a sledge load of firewood. Two rubles for the hill of Golgotha, two rubles for blisters on our shoulders! Two rubles. What appalling exploitation, what contemptible mockery, what coldly calculated, deliberate murder

Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 112

People barely manage to buy bread with their food talons. Starvation and untreatable diseases start to kill people, which could easily have been avoided because 500 tons of fish were stored nearby: Travkin could get some additional food for us from Yakutsk, but he doesn’t. There is fish rotting in Konstantinovka, while we die of starvation because supervisor Mavrin won’t allow us to have it. He’d rather let it go off and dump it in the spring (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 112). If exiles complain that they cannot go to work and earn their bread because they are weak from hunger, Sventickis asks in mock surprise: Famine? What famine? There is no famine. The food you get is adequate and wholesome… (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 101).

The counterbalance

How can Dalia overcome such a degrading and debilitating environment, which is not nurturing for a child, where the conditions serve only to stunt the child’s growth and development? When the seven-grade school opens in Trofimovsk in December, Dalia rushes to school after an exhausting four hours of work with the logs: At twelve o’clock, I feel reborn. Everyone goes for lunch. I too take off my rope, drag my enormous, sack-wrapped feet into the barracks, fortify myself, grab my briefcase and Krikštanis’s inkwell, and run to class (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 56). Although the wounds sustained from hauling the logs are painful, it is here that she regains her dignity: The place is warm, there are candles, light, I’m being addressed as a person (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 57). Dalia observes that 45 minutes of a lesson in exile feels like a mere moment. For her, school is an opportunity to be a child, to experience ‘normality’. It is also an opportunity to learn something new in the daily routine of exile. At the end of the school day, she and her other lice-ridden, hungry classmates return ‘home’ to their cold caves and look forward to the next day when they can go to school again. Dalia seizes every opportunity to read and study whenever there is light in the normally dark barrack, even if it means studying by the light of a stolen candle and by the side of a dead person because learning is the affirmation of life:

Our barrack has been illuminated. A candle stands on either side of Atkočaitienė’s corpse – two whole candles – which means that someone has been stealing candles from the town office and hoarding them. (…) I’ve never seen so many lice – entire divisions march across her nose, her eyelids, her lips, then disappear into her neighbour’s rags. Taking advantage of the candlelight, I stand there reading the history of the Middle Ages

Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 63–64

A child unbroken

The question remains: does this young girl, a teenager in the making, faced with hunger, contempt, inhumane living and working conditions, surviving in a climate inappropriate for human habitation, and seeing the helplessness of adults all around her, does she break? No. She does not. She seems to have gained strength from her happy, secure, and stable childhood in independent interwar Kaunas. That’s where her character began to form, where her values were shaped. Dalia’s memories of a happy, secure childhood in Kaunas motivate her to survive. It is home that sustains her: I tell Marytė about the theatre, the opera; we sing arias, we cry our hearts out talking about our school days and the shows. Afterwards, we stretch out on the logs for a nap. Towards evening, we stack another pile [of logs], this one four meters square in size (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 196–197). When Dalia’s mother seems very close to death, Dalia chants two things like a mantra to give her mother hope and keep her in this world – we will survive, we will return: Mama, Mama, (…) we will live, we will survive, we will return. We will, Mama. Oh, Mama, I promise! (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 56). Literary scholar Kamil Pecela draws the following conclusion from Dalia’s narrative: The children are the main moral pillars, in contrast to the adults, who were quickly broken by the starvation, hard labour, and captivity (Pecela, 08.01.2020).

Victor Frankl, in his book “Man’s Search for Meaning”, mentions similar arguments that have helped people to survive: This intensification of inner life helped the prisoner find a refuge from the emptiness, desolation and spiritual poverty of his existence, by letting him escape into the past. (…) Our thoughts, writes Frankl, often centred on such details, and these memories could move one to tears (Frankl, p. 58–59). He also mentions the prisoners’ ability to cling to positive details, such as the beauty of nature, a sense of humour, and a sense of future purpose, which helped them to survive. Such testimonies from life in extremis are also found in Dalia’s memoirs. Both authors describe their survival in very similar terms. Frankl says: As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before (Frankl, p. 59). Meanwhile, one of Grinkevičiūtė’s strongest climactic passages sounds like this: Yet what splendour above. The northern lights are a magnificent web of colour. We are surrounded by grandeur: the immense tundra, as ruthless and infinite as the sea; the vast Lena estuary backed up with ice; the colossal 100-metre-pillar caves on the shore of Stolby; and the aurora borealis (Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 73).

Dalia becomes an adult, responsible for her own life and her survival earlier than most adolescents. After the hard winter of 1942, she and her friend are invited out to the tundra to meet two young radio operators who make a point of finding a radio station with beautiful music. The young girls burst into an uncontrollable weeping that speaks not only of their pain and loss and immense longing for home, but also relief that they have survived. But the abandonment with which they release their pain in weeping is also a hint of Dalia’s determination to testify in writing to the triumph of willpower that the girl’s survival involved.

I just remember jumping up and running onto the tundra, falling face down in the snow and crying. Rivers of tears until we could hardly breathe for the tightness in our throats. I have no idea how long we lay there trembling – the frozen tundra in our embrace – and sobbing. Our stolen youth weeping for its stolen homeland

Grinkevičiūtė 2018, p. 200

Vytenė Muschick is a Lithuanien and has been living in Berlin. She has translated the fiction of Henning Mankell, Karin Alvtegen and Camilla Läckberg from Swedish into Lithuanian, and also translated the memoirs of Dalia Grinkevičiūtė into German and is a co-author and curator of exhibition about her “Rooms/ Overcome distances”.

References:

Burauskaitė Birutė, Lietuvos gyventojų genocidas [Genocide of Lithuanian population], t. 1. LGGRTC, 1999;

Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, Washington Square Press, 1984;

Grinkevičiūtė Dalia, Shadows on the Tundra [Original title Lietuviai prie Laptevų jūros], Pereine Press, 2018, p. 15 (translation Delija Valiukenas);

Pecela Kamil, Lagerio veidas nežmoniškas [The face of camp is inhuman], in Bernardinai.lt, 08.01.2020.