Dmitriy Panto

The First World War (1914–1918) was the greatest epochal experience for the entire world, and especially for Europe. Millions of people were killed or died from disease and hunger; thousands of buildings were destroyed; the new ways (military equipment such as tanks, aircraft, and chemical weapons) of conducting war – all this resulted in enormous changes on the map of the world and in people’s minds. The war forced hundreds of thousands of people to abandon their homes and seek shelter in safer places. Poles were not only active participants on both sides of this conflict but were also victims of military operations and political decisions.

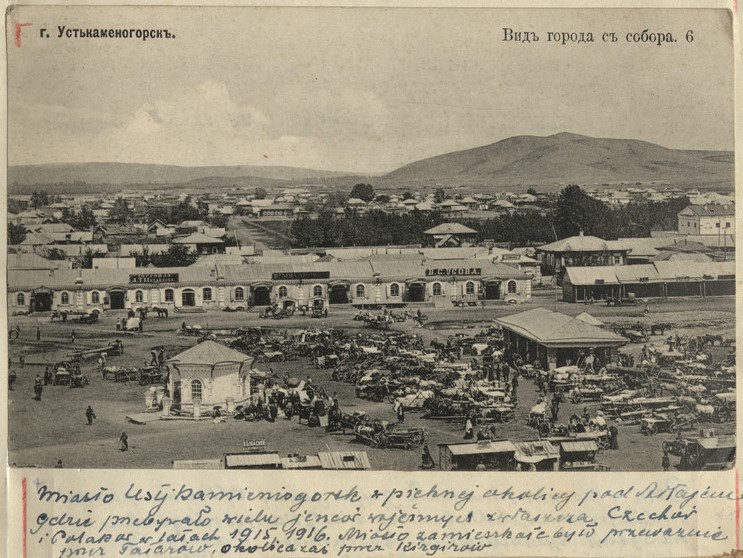

As a result of a decision of the tsarist military authorities, hundreds of thousands of residents of the Kingdom of Poland [above all, inhabitants of the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania – EN] had to leave their homes in mid-1915. Poles living in the Łomża, Suwałki, Lublin, Płock and Siedlce governorates were sent deep into the Russian empire. The evacuation that began had a mass character. The evacuees, the so-called biezhentsy, reached Siberia and Central Asia at the turn of 1916. It is worth recalling that, according to researchers’ calculations, the Poles living in the Russian Empire at the end of World War I included about 1.5 million biezhentsy, about 100 thousand prisoners of war, over half a million soldiers, about 300 thousand resettled persons, and about 3 thousand exiles.

The biezhentsy, who poured like an avalanche into Siberia, the Caucasus and Central Asia, did not receive proper support from the state. The routes they had to take were often chaotic and improvised. Many people fell ill and died along the way. Often, the areas where the wandering Poles had to live in or stay for a while were not suitable and conditions were atrocious. The feeling of uncertainty and the temporary nature of this migration was also tormenting. The mental state of the travellers was often terrible.

Due to the incompetence of the state and the necessity to help needy compatriots, the Central Citizens’ Committee was established in Russia. The Polish Society for Aid to War Victims also operated from the first days of the war. Moreover, there were charitable societies operating in the Catholic parishes to which the biezhentsy went. Also, the Central Citizens’ Committee had headquarters in all major cities and transport hubs. In Kazakhstan and Central Asia they were, among others, in Kokshetau, Petropavlovsk, Tashkent and Samarkand. Charitable organizations divided their individual areas of activity between themselves: the Central Citizens’ Committee focused on work in smaller towns and villages; the Polish Society for Aid to War Victims worked in larger cities, while Catholic charitable societies operated in parishes and larger communities of believers.

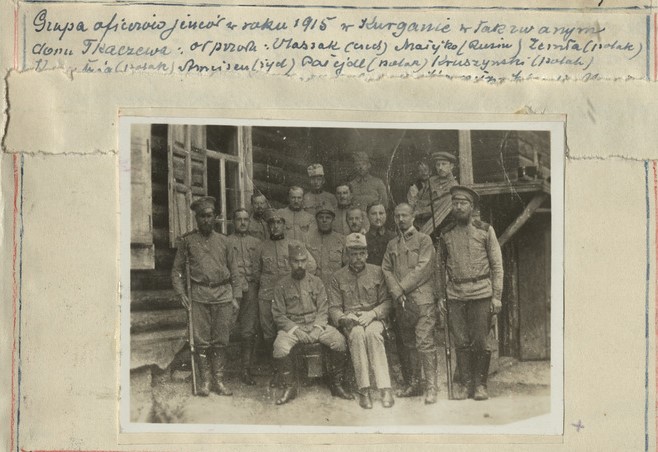

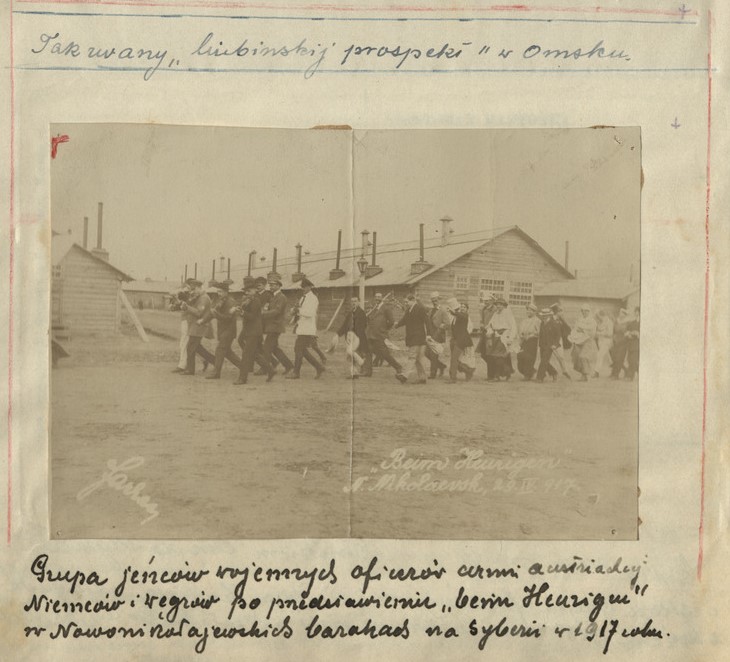

Polish prisoners of war were sent to the south, from where – in the authorities’ opinion – it was more difficult to escape. During the war, between 50 and 100 thousand Polish soldiers fighting on the side of the Central Powers were taken into Russian captivity. They were held in specially constructed camps. The memories of Poles imprisoned there clearly illustrate the conditions in which they had to live: “The Troitsky camp stretches over three kilometres. On one side, it borders the steppe; on the other, it slopes down towards two large springs… […] In the meantime, the winter [of 1916 – DP] came, harsh for Turkestan, and confined the ragged soldiers to their barracks and bunks. For the 600 people in a barrack, there were usually 60 pairs of usable shoes. […] The condition of the underwear department was equally disastrous. […] Often, there were people without any underwear at all”. The prisoners were allowed to receive money transfers or parcels and were provided with additional assistance by Red Cross agencies (e.g., the Central Committee for Prisoners of War). The captives had to work, for example, in agriculture and construction, and they often also performed their learned professions.

The arrival of such a large number of Poles in Central Asia dramatically changed the face of the Polish diaspora, which had inhabited these areas in large numbers since the 19th century. Local Polish communities were given new opportunities to practice their language, traditions and Catholic faith, which undoubtedly influenced their self-awareness and the awakening of Polish national identity. Their sudden contact with compatriots strengthened their fading ties with their homeland, which gradually motivated millions of Poles in the Urals to return to independent Poland. The Apostolic Administrator of Siberia, Father Gerard Piotrowski OFM, an eyewitness to these processes, recalled this period as follows:

“…a mass wave of Catholics came to Siberia after the outbreak of the European war in 1914. Thousands of Austrian and German prisoners of war appeared in many Siberian cities and villages, among them a huge number of Poles from Galicia, Poznań, Pomerania and Silesia. While non-Polish prisoners felt completely alien in Siberia, Polish prisoners almost everywhere encountered numerous well-organized Polish-Catholic colonies, in whose life they immediately took part. The cultural and religious life of Catholics in Siberia was strengthened by the cooperation and work of thousands of Poles. And how lively this pulse was evidenced by the founding of many Polish societies, the renovation of the Lord’s temples, and even the construction of new churches (e.g., in Tashkent, Turkestan) in all corners of Siberia. In addition to prisoners of war, many civilians also arrived at that time, the so-called biezhentsy, who fled to the east from the Polish territories most severely ravaged by the war or were forcibly displaced by the Russian government. They came with their wives and children, and many of them settled in Siberia for life”.

Among the most important Polish organizations established after the February Revolution of 1917 was the Polish National Committee for Siberia and Russia. Most of the Polish organizations operated until 1920. Some of their members left Siberia with the 5th Siberian Division, while the rest, together with other Poles, left as part of the repatriation of 1921–1924.

The everyday life of the biezhentsy was difficult. In unfamiliar territory, often with little or no knowledge of the Russian language, they had to cope and earn enough to survive. Larger urban centres were overcrowded, so they sought survival in remote Siberian or Asian villages. Children and the elderly were in the most difficult situation.

Ferdynand Goetel recalls a typical story of biezhentsy of that period:

“In response to our inquiry, he told a short, ordinary story of a biezhentsa. Taken from his parents by the Cossacks in Lublin province, transported to Minsk and kept there for three months, he finally got on a train that took him to Andijan. From Andijan, he was taken to the countryside by the wife of a mobilized reservist, for whom he worked for a year and a half to earn his living”.

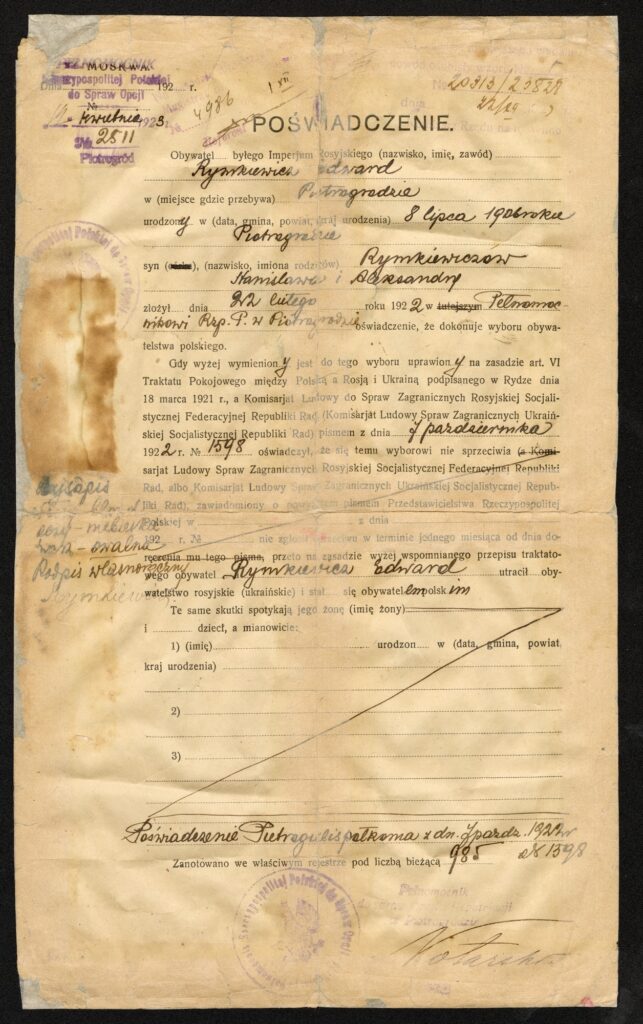

Throughout Russia, preparations for the return of Poles began while the war was still ongoing. After the outbreak of the February Revolution, this process was continued, but the beginning of the civil war in Russia halted it. It was not until September 1921, when a delegation of Polish authorities arrived in Siberia, that the repatriation process began. The legal path to its implementation was opened by the Treaty of Riga (Peace Treaty between Poland, Russia and Ukraine, signed in Riga on 18 March 1921). According to this document, all persons of Polish nationality were given the opportunity to return to Poland and obtain Polish citizenship.

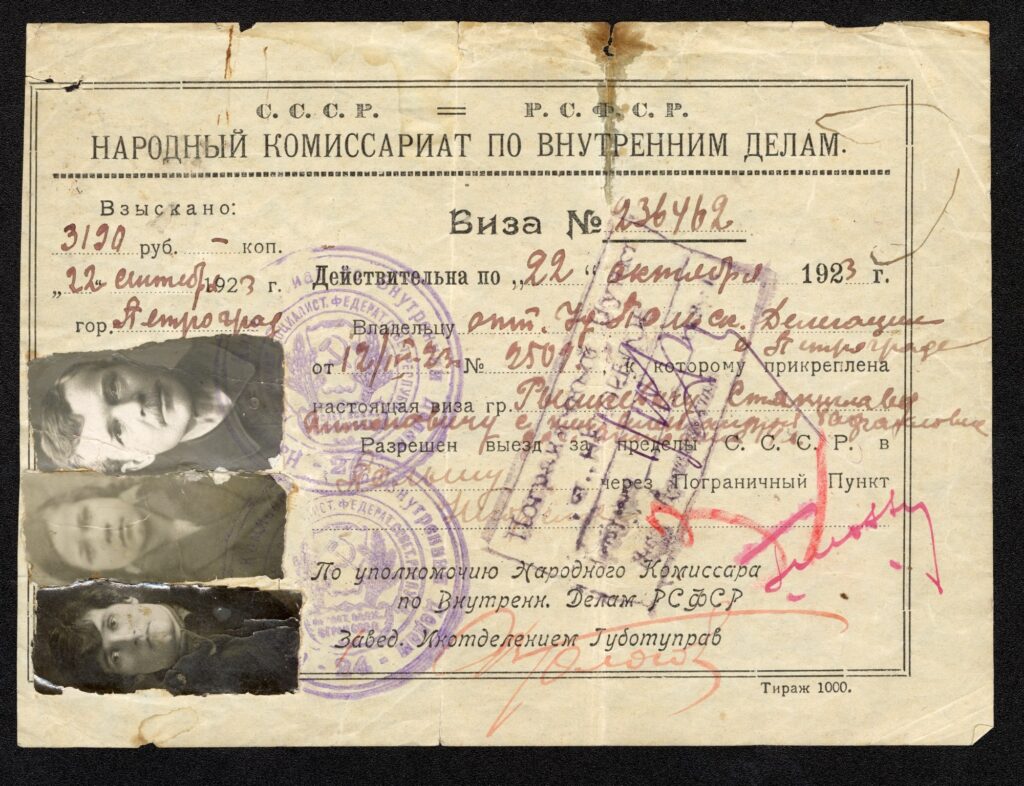

Thanks to the new legal status of Poles, their mass repatriation became possible in the years 1921–1924. The mass scale of this undertaking required close cooperation and clear procedures from the Polish and Soviet authorities. In connection with this, evacuation committees were established: SIBEVAK for the Siberian area, and KIREVAK for Central Asia. These committees consisted of smaller governor evacuation committees (GUBEVAK), which were to cooperate with the central evacuation committee in Moscow (CENTREVAK) and with the committees in Kiev (UKRAVAK) and Minsk (BELEVAK).

People who wanted to return to Poland had to submit evidence proving their Polishness and their ties to Poland. This could include a passport, birth certificate, military ID, membership cards of Polish organizations, certificates from Polish schools, and knowledge of the Polish language. Often, certificates signed by three people of Polish nationality were also submitted, confirming the fact that the given repatriate had Polish nationality. Sometimes they were issued by the priests of local Catholic parishes. As shown, certifying Polishness was not always easy, especially since some people had lost all their property (including documents) during the civil war and had changed their place of residence several times. According to SIBEVAK instructions, the most important documents were those issued before the 1917 revolution, while documents from the period of the revolution and the civil war were subject to additional verification. Another problem was providing the evacuation committee with a photograph, which had to be pasted into the questionnaire, because at that time there were not photographers in all locations. According to SIBEVAK instructions, after being issued with permission to evacuate, the person had to leave the territory of Soviet Russia within six months. Often, due to the lack of documents and the illiteracy of people applying for repatriation, their interests were represented by the local Catholic parish priest. It is worth emphasizing that the repatriation of Poles had a very strong impact on the Catholic Church in Siberia and Central Asia because most parishes became deserted, especially since Catholic priests working beyond the Urals also took advantage of the opportunity to return to their homeland.

It is worth remembering that the repatriation of Poles was also carried out in the conditions of the famine that was prevalent in Bolshevik Russia at the time. Hundreds of thousands of people were in transit in search of help and food. These factors cause certain problems in research on returns from Central Asia. For example, the issue of repatriation was handled by a different office in each region, each of which defined repatriates differently, causing additional confusion. Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Germans and Austrians were also returning to their homelands.

The systematic process of repatriation from Central Asia began in July 1921. During this period, 1 to 2 thousand people passed through KIREVAK points every day. The KIREVAK management drew attention to the need for frequent disinfection of points and transports. In places where returning refugees gathered, in addition to the spread of infectious diseases, robbery and theft flourished. Funds were needed in order to eliminate criminals, provide food and disinfectants, but there were none. Another problem was the division of competences. There were tensions and misunderstandings between KIREVAK and local authorities, which affected the fluidity and continuity of repatriation.

The evacuation process in the field was as follows: the militia or administrative bodies of individual counties and governorates drew up lists of Polish citizens living in a given area; then, based on their documentation, lists of biezhentsy were drawn up for repatriation to Poland. It is worth emphasizing that before signing the relevant international agreements and issuing instructions on repatriation, local authorities were advised not to accept individual applications from Poles. According to this instruction, the registration of prisoners of war and civilians in Central Asia would proceed as follows: each person registering had to present an identity card and, if relevant, an ID from their place of military service. Married people also had to provide a marriage certificate and birth certificates of children. The registrants had to check the credibility of the documents and on this basis determine the citizenship of the given prisoner. Then, a certificate was issued in duplicate: one copy was left with the evacuee, the other in the office. Depending on the office and the governorate, a more or less detailed list was prepared. For example, The Notebook for the Registration of Biezhentsy – Poles for 1922 in the Kokshetau District contained the following information: name and surname, age, temporary place of residence, permanent place of residence, and documents on the basis of which the registration was carried out. If repatriation was prevented by illness or some other misfortune, repatriates would not lose their right to return to Poland at a later date.

Both prisoners of war and biezhentsy could count on financial assistance from the state, but the former received it from local war commissariats in the amount of 64 rubles per month, while the total amount of payments for one person could not exceed 1,500 rubles; in the case of biezhentsy, the allowance was paid by CENTREVAK, but only in exceptional situations, such as a funeral, birth of a child or illness. The rest of the allowance was given by CENTREVAK in kind.

One biezhentsy, engineer Witold Lebiedziński, remembered his journey from Asia to Poland as follows:

“We set off for our homeland on 7 September 1921, full of the best hopes, not anticipating how much hardship, suffering, and disappointment awaited us… […] The journey of our echelon began very successfully. We travelled quite quickly, considering the conditions at that time. After five days we reached Tashkent, having picked up on the way wagons with compatriots who had been repatriated from Charzhuy, Samarkand, and Chernyaevo. But Tashkent stopped us for over a week. There, they formed a long special train from the wagons with exiles. Then they began to supply necessities to it and take care of various formalities. It took quite a long time, but finally we left Tashkent. The food supplies that the Soviet authorities issued us for the journey were very poor and could only last a few days, so they had to be replenished on the way. Besides, no one counted on Soviet supplies; everyone, when setting off on the journey, stocked up on food. […] After leaving Tashkent, the hardships began very quickly. The pace of the journey slowed down. The train stopped for several days at every major station. We were told that this was due to the lack of steam locomotives, the condition of which was truly desperate at that time on the Russian railways. We had to bribe the railway service staff with gifts in the form of flour, groats, dried fruit, etc., but the long journey that still awaited us demanded great economy in using the supplies we had taken. […] Meanwhile, the harsh autumn was becoming increasingly severe as we approached the cold Orenburg region. The wagons were unstocked and of little use for such a journey; they were not teplushkabut ordinary freight wagons, with walls full of cracks and holes, not equipped with stoves. It was necessary to seal the walls of the wagons on the way, try to get stoves, and prepare for the winter. The echelon was completely unstocked with firewood. […] Meanwhile, the journey began to exhaust the strength of the weaker ones. Illness was common, as was the funerals of those whose strength could not withstand the hardships of the journey. […] Finally, on the afternoon of 7 November 1921, two months after leaving Ashgabat, we reached one of the distant stations of the Moscow railway junction, located 10 versts from the capital of red Russia”.

The next stage was the journey from Moscow to Poland, which took the next few weeks. Weeks of hardship and uncertainty. After returning to Poland, the repatriates faced new problems because they had to reorganize their lives in an independent country. In the period from April 1921 to June 1924, over 1.1 million people repatriated from the territories of the then Soviet Union.

Dmitriy Panto,PhD – certified curator, Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk

Translated by Sylwia Szarejko