Dr Henryk Głębocki interviewed by Tomasz Danilecki

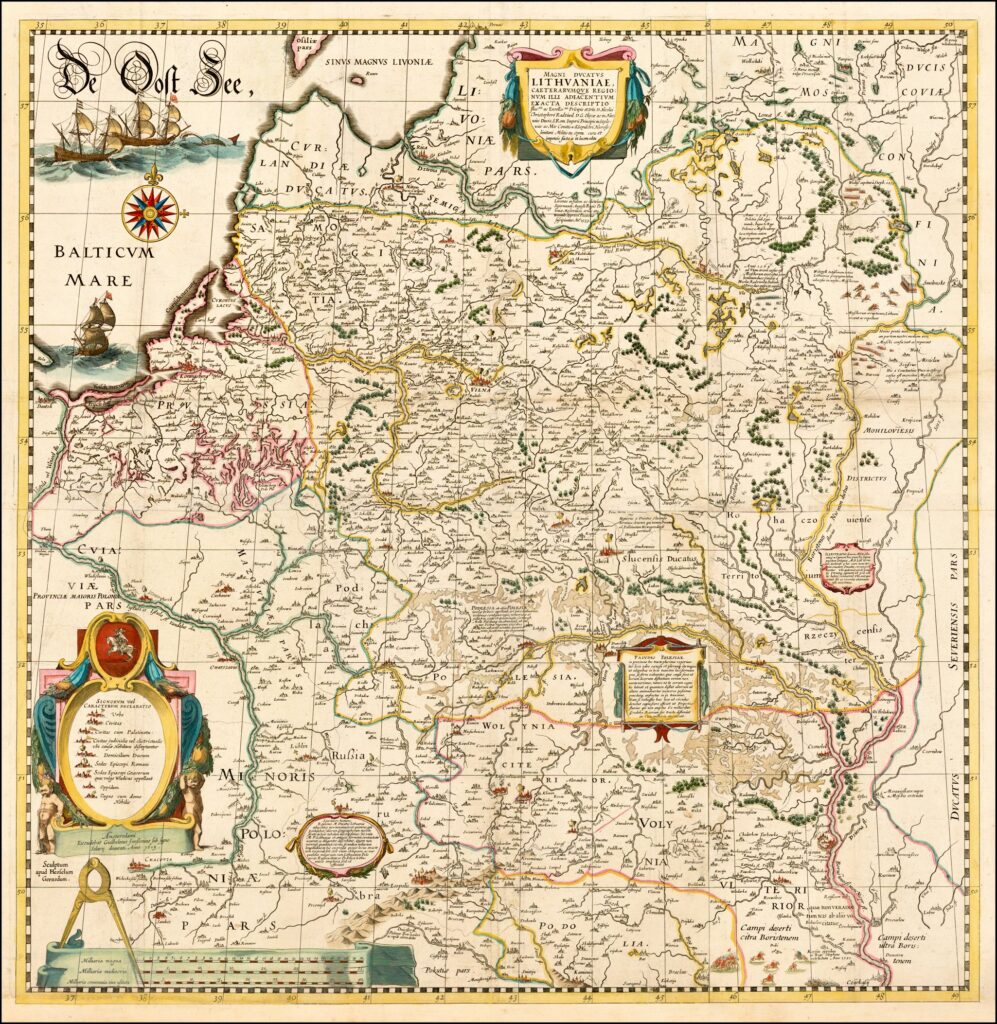

Tomasz Danilecki: We will attempt to reflect on the internal differences in the Russian elites’ approach to the integration of the area of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania with the empire after the destruction the First Republic of Poland during the 19th century.

Henryk Głębocki: The term used in Russia to describe a number of complications caused by Polish desires to regain sovereignty and freedom aspirations was the so-called polskij wopros – the Polish question. It is reasonably questionable when Russia recognised that the Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands dubbed the Borderlands, which it dreamt of as the natural inheritance of Kyiv Rus, as well as which it supposedly had developed from, were different from itself. For example, this was the result of the continuation of another legal system here – the Statutes of Lithuania, which were still maintained until 1840.

The border established on the Bug River after the Third Partition would continue to be rebuilt until the 20th century. The incorporation of the eastern lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth entailed not only a geopolitical shift of Russia to the centre of the continent and at the same time towards the centres of Western civilisation, but also the acquisition of the most densely populated and highly developed provinces (apart from the Baltic governorates), with the largest urban centres across the Eurasian Empire. Only after 1795, when Russia began to develop the area, did it become apparent, to the astonishment of the tsarist officials (chinovniks), that more than 60% of the empire’s social elite spoke Polish, were of the Catholic faith and, in fact, were so attached to the traditions and republican culture of the First Polish Republic that they had no intention of changing their identity. A particularly telling manifestation of this otherness was the reluctance to enter state service, which traditionally, despite the formal abrogation of such an obligation in the mid-18th century, was associated with the elite status in the country of the tsars. It is worth adding that the Russian gentry were not granted rights comparable to those of the Polish gentry until 1785 as a result of a charter by Catherine II. Therefore, after the Third Partition, a dilemma came up: what course of approach should be taken towards the new subjects in this situation? Initially, attempts were made to ‘implement’ the traditional methods developed by the empire against okraina (borderland) over the centuries of its expansion in the lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Following the renowned British analyst of Russia, Geoffrey Hosking, it can be noted that, unlike the European powers, the country did not so much ‘have’ its empire as simply ‘had always been’ an empire. In other words, this was the structure it was founded on. Although the country has disintegrated several times, it has always attempted to return to its original state as the contemporary upheavals and the ongoing aggression against Ukraine also demonstrate. Part of this very identity of the Russian state was the methods developed over centuries, which could be described as an attempt to loyalise and enlist the elites of conquered lands in collaboration. A prime example of this is the fate of the German gentry in the Baltic provinces, who, after their incorporation into Russia on the basis of the so-called Nystad Capitulations of 1721, were granted greater privileges than they had enjoyed under the Swedish reign.

Similar reasons were behind the strategy applied to Poland after the Third Partition. In the first phase, during the reign of Catherine II, an attempt was made to subject the incorporated territories to administrative unification combined with repression of participants in the Kościuszko Uprising and the war in defence of the May 3rd Constitution. However, soon after Catherine’s death, her son Paul I, who hated his mother for the murder of his father, Peter III, reversed this policy and restored the gentry self-government, the image of which we know, for example, from the pages of Pan Tadeusz (Sir Thaddeus) by Adam Mickiewicz. Such a strategy, in contrast, clashed with the strength of Polish culture and republican tradition. The ideas of freedom expressed through Polish patriotism stood at antipodes of the autocratic Russian tradition. The memory of an independent state lasting for eight centuries still proved attractive to the Polish elites. This was reflected in the involvement of their many representatives in the Kościuszko Uprising and later in the Napoleonic epic, as well as continued hope for the recovery of a whole and independent Republic of Poland. The very word ‘independence’ in the modern sense became widespread at the time of the Partitions when faced with the loss of subjectivity. The coping strategies of that generation of Polish gentry in the absence of their state were aptly described by Prince Józef Poniatowski. He referred to ‘two consciences’: one presented to the invader, and the other, deeply hidden, expressed only at home with the hope of regaining independence. (Prof. Jarosław Czubaty wrote an interesting book by this title.) The Napoleonic era became a period which saw the ‘Polish card’ staked, and fiercely so, by both Napoleon and Alexander I. The latter, perhaps the most liberal of the Russian tsars, also wanted to have ‘his Poles’ – a pro-Russian party – as a tool for playing the game against France and the German powers. He therefore deluded Polish politicians into thinking that it would be possible to recreate the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, together with its eastern lands, under the Tsar’s sceptre. As a result of Napoleon’s defeat, this concept seemed to have won at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Unfortunately, against the resistance of the other powers, only the minor Kingdom of Poland was negotiated with the right to an ‘internal’ extension to the remaining lands of the Russian Partition.

Do you think, however, that the dreams of the Poles about the restoration of statehood, especially encompassing the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, were probably only an expression of wishful thinking?

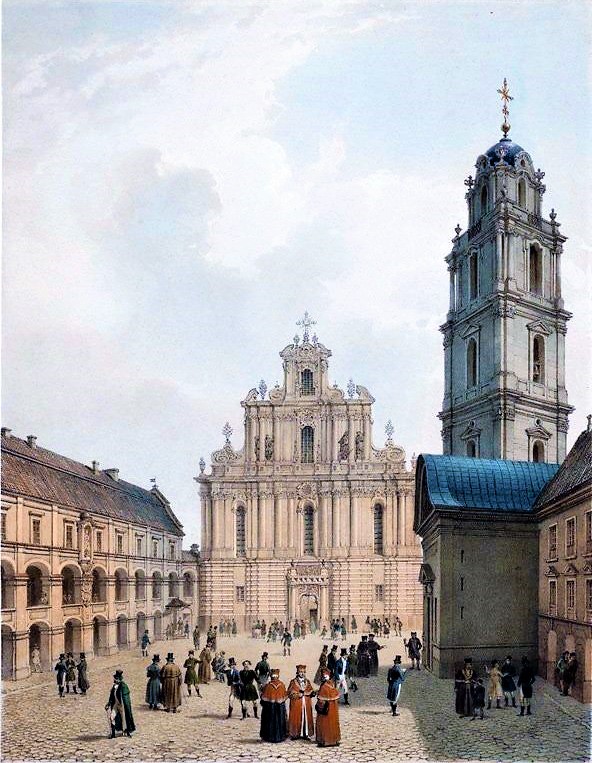

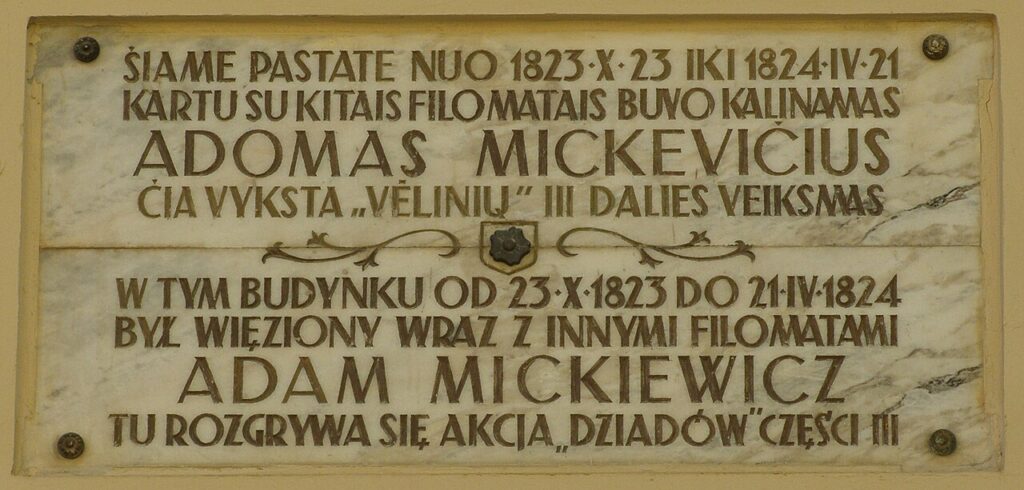

The Polish people’s hopes for the fulfilment of these promises and the subsequent disappointment – also influenced by the violation of the constitution granted to the Kingdom (the most liberal in Europe at the time, we should add) – became a source of frustration, especially for the younger generation. This was expressed in successive plots and led to the outbreak of the November Uprising. The eastern lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, only called Borderlands in the 19th century, remained within the borders of the empire and came under the rule of Alexander I in perhaps the most favourable situation for them throughout the century. Thanks to the involvement of Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski and his high position at court as the Tsar’s friend, a genuine cultural and school autonomy was established here. It was manifested in the Vilnius school district, which encompassed the entire eastern lands of the former Commonwealth, with the University of Vilnius at its head. This was where a significant part of the intellectual, literary and cultural elites came from, including Joachim Lelewel, Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki. This fine generation of the late Enlightenment and early Romanticism, hailing from the Borderlands, created a canon of Polish culture and literature that endures to this day, appealing to the living memory of the independent Republic and idealising its free traditions in poetic form. The administrative posts and even the governors’ offices were then filled by Poles. Thus, there was reason to mourn Alexander’s untimely death in 1825 as a ruler who, after the defeat of the Napoleonic option, offered the maximum that could be obtained in the reality of the time. Particularly from the perspective of the generation that went through the ups and downs of their hopes, from the Four-Year Sejm, through the May 3rd Constitution and the war in its defence, the Targowica Confederation, the Second Partition, the Kościuszko Uprising, the Third Partition, the legionary epic and the hopes awakened by Napoleon, which reached their apogee and perigee in 1812, and the unsuccessful invasion of Moscow. This is why ladies in Warsaw and Vilnius, mourning the Tsar in 1825, called the late Alexander Pavlovich ‘our angel’.

Now both Congress Kingdom and the Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands became a kind of laboratory for the constitutional changes under consideration, which were also intended to be introduced in Russia. The Lithuanian Seperate Corps formed in 1817, uniformed like the Polish Army and placed under the command of the Tsar’s brother, Grand Duke Konstantin, who headed the Polish army and simultaneously administered the western governorates, promised to fulfil Alexander’s promises. But these were always made to the Polish elite unofficially.

What made Nicholas I reluctant to continue this liberal policy towards the Poles?

The stance of the empire’s policy towards Poles changed abruptly in the early 1820s, i.e. still during the reign of Alexander I, under the influence of the revolutionary threat in Europe and the views coming from Russia itself. The Tsar had to abandon his liberal and constitutional experiments, which were also of importance in terms of propaganda towards foreign countries and were part of the geopolitical game with Prussia and Austria. This change was first reflected in the repression of the Philomaths and Philarets (the student organisations in Vilnius). It heralded a new turn – the abolition of cultural autonomy and guarantees for national rights. Henceforth, the notorious senator Nikolai Novosilcov, the supervisor of the secret police and behind-the-scenes activities against the Poles, and the Tsar’s hated brother Konstantin in Warsaw, became the faces of this new policy. Both tsarist proconsuls were portrayed remarkably aptly in the masterpieces of Romantic drama, Mickiewicz’s Dziady. Part III (Forefathers’ Eve. Part III) and Słowacki’s Kordian.

The stance they expressed was soon intensified by Alexander’s brother Nicholas I’s rise to power. He ascended the throne in December 1825 ‘over the dead bodies’ of the Decembrists, who were massacred during their failed revolt in the Senate Square in St Petersburg. Not only as a result of this experience, the new Tsar saw a deadly revolutionary threat in any form, be it lawful, parliamentary opposition in the Kingdom of Poland. Unlike his liberal brother, he never showed liking for the Poles. He couldn’t stand Prince Czartoryski. He was brought up diffently to Alexander: not on the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau but on the counter-revolutionary literature, Nikolai Karamzin and praising the tsar. On the Polish question, he was committed to the political legacy of his grandmother Catherine II, continuing the lines of expansion already set by her in Central Europe, the Balkans and the East. The conquest of the Polish lands was a prerequisite for this policy. As Napoleon once so aptly noted, Poland was a geopolitical ‘keystone of the vault’ of this part of Europe. As it was during the Duchy of Warsaw, it could have been an anti-Russian march or a Russian military base to checkmate its German neighbours. The control of the lands beyond the Bug River completed this geopolitical vision. However, this era also saw the emergence of new reasoning – citing Karamzin – that they were also the cradle of Russian statehood and Russian identity. Influenced by Romanticism, the idea of a ‘Russian world’ was born, with Ukrainian and Belarusian lands at its heart.

In the same epoch, a new phenomenon developed, recorded in the fundamental works by Karamzin, History of the Russian State, through to Smuta (Time of Troubles) of the early 17th century. Its author was an eminent literary scholar and adviser to the tsars. The first volumes were published in 1818. In this epic vision of Russia’s history, the empire was portrayed as a heritage belonging not only to the ruling dynasty but also to the Russian people. An important theme therein was the justification of Russia’s historical rights to rule over the Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands as a succession from Kyivan Rus. At the same time, Karamzin defended Tsarist autocracy as the keystone of the empire’s entire political system and its legacy arising from successive conquests. As early as 1819, when the possibility of reviving the Kingdom of Poland within the entire Russian Partition was quietly debated, this historian and ideologist at the same time made a vehement protest. Not only did he express his private view in it, but also the position of the influential anti-Polish coterie centred around Alexander’s sister. The next Tsar, Nicholas, was already very strongly influenced by this monarchical, imperial and conservative approach. Admittedly, he still tried to maintain a consensus with the Poles on his terms, but only in the Kingdom of Poland. Now there was no question of any concessions to the inhabitants of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands. The policy towards both these parts of the Russian Partition logically complemented each other. The new Tsar envisioned that the prerequisite for maintaining status quo on the Vistula was the gradual unification of the lands beyond the Bug River. Several signs indicate that already at the time, before the 1830 uprising, plans were made for the gradual russification of the western governorates, including proposals of the future liquidator of the Uniate Church, bishop Joseph Siemaszko.

Therefore, the November Uprising became a convenient excuse for Nicholas not only to withdraw privileges from the Kingdom of Poland, but also to work towards the gradual unification of the eastern lands with the empire…

Obviously, the November Uprising gave Nicholas a chance of both revenge and ruthless as well as unstoppable eradication of Alexander’s Polish experiment. The best-known signs of this new policy became not only the massive repression of participants in the insurrection and the confiscation of property but also the destruction of school autonomy. This was accompanied by the closure of Polish schools, academic institutions and the entire Vilnius academic circle frontlined by the Vilnius University and Krzemieniec Lyceum, and then followed by cultural russification. All this was made complete by the dissolution of the Lithuanian Separate Corps and the gradual abolition of the legal system inherited from the First Republic. The school structures under the new Saint Vladimir University, established in Kyiv with the mission of russifying these lands, became the instruments of this policy. The ruthless military-police terror and system of repression, especially after the discovery of Szymon Konarski’s conspiracy in 1838, was further exacerbated by the dissolution of the Greek Catholic Church in 1839. It was intended to cut off the ‘Ruthenian’ population of these lands from Polish influence. The assimilation policy was also pursued by recruiting the rich gentry into state service and persuading them to collaborate with the Tsarist authorities. However, the most effective tool for limiting the reach and strength of the Polish element in the Borderlands turned out to be a major undertaking with all the features of social engineering, i.e. large-scale vetting of gentry, which began at the time. It entailed the loss of civic rights for the multitude of petty gentry representing Polishness, these ‘lords of themselves’, homesteaders and backwood dwellers. The empire’s crackdown on this population was a huge undertaking, a lengthy process whose source research was begun by French historian Daniel Beauvois. In the 1980s, as a Frenchman, he was allowed into the Kyiv archives and, in a then famous book, showed what the scale of this social engineering-like operation was. But today, also thanks to the conclusions, critical of Beauvois, of eminent Polish researchers, especially Prof. Leszek Zasztowt or Prof. Jolanta Sikorska-Kulesza and many others, we know that this phenomenon did not begin in the mid-19th century but already in the times of Nikolai Repnin, one of the first governors of Vilnius. At that time, they started to think how to get rid of the overabundance of free people with civil rights, who at the same time represented the Polish identity. These were entire villages and the so-called noble areas, inhabited by people who lived a bit like peasants, but were free, retained historical memory and a commitment to faith, homeland, freedom, personal dignity, which was shocking to the Russian chinovniks.

And that was why, from at least the 1830s, the intention was to deport them…

The intention was to deport them as early as the 1790s. However, they refrained from doing so, especially during the times of Tsar Paul and Tsar Alexander, who played the ‘Polish card’ with Napoleon. Although it did not ultimately go as far as this, plans for mass deportations – methods characteristic of imperial rule – had been made earlier, only to go initially into the bin or to the bottom of deep drawers in ministerial cabinets, not without the influence of Father Adam Jerzy Czartoryski or other Polish dignitaries in the Tsar’s service. These projects of ‘reduction of the nobility’ were revisited after the fall of the November Uprising. On the broadest scale, this was attempted by the wartime governor Dmitry Bibikov, who devised a simple system that was later replicated in the Kingdom of Poland: all those who considered themselves to be nobility were required to show ‘papers’, i.e. proof of nobility rights. In the gentry ‘neighbourhoods’, where it was known who was who from generation to generation, where documents were burned with each successive conflict, it was difficult to formally prove one’s ancestry… As a result, a typical Russian ‘show’ was organised: if someone was wealthy enough, they could turn to the heraldry office in St Petersburg, pay a bribe to the chinovniks and get the so-called ‘coat of arms from the neighbouring side’, thus assigned at random. But most of the nobility did not have such means. They were then turned into the so-called one-horsemen, whose status was something intermediate between nobleman and peasant. Thanks to this procedure, they could be russified within a generation or two. Falling out of the noble status in the feudal social system of the empire was a disaster. It meant that one paid taxes, provided recruits, was subject to corporal punishment. Elementary human rights were simply lost. The whole of this huge, spread over a couple of generations, brutal socio-technical operation was to destroy the remnants of the socio-cultural body, which was the heritage of the political, republican nation of the First Polish Republic. Yet the final crackdown on these Borderland communities was not to occur until the Soviet era, in the 1930s, when the Polish population located beyond the so-called Riga border, around Minsk, Podolia and Volhynia, was to be simply exterminated. We still know too little about the scale of the empire’s similar operations, which involved at least several hundred thousand people. Only recently, from archival sources, another phenomem has come to light and begun to be described in greater detail: the huge scale of the conscription of recruits into the tsarist army. During this era, it meant service lasting 20–25 years with little chance of surviving and returning to one’s home country. According to an old estimate, from before the opening of Russian archives, made by the renowned expert on the 19th century Stefan Kieniewicz, based on reports from British diplomats, as many as 400,000 young people were ‘selected’ as recruits from the Taken Lands. More recent data, based on material stored in Russian military archives, although slightly reducing these figures, confirms the enormous scale of the sheer appalling practice of selecting ‘living contributions’ from the youth generation of the time, usually from among its most active and patriotically-minded population. After being imposed by force on them in tsarist uniforms, these victims of the empire were turned by force into its servants and soon into its defenders, sent to further conquests in the distant eastern regions, especially the Caucasus and the so-called Orenburg Line, the steppes of Kazakhstan and southern Siberia. Deliberately dispersed here for fear of mutiny, Poles made up as much as 20% of the stationed soldiers. According to military documentation researched by Prof. Wiesław Caban, it has been established that from the area of the Kingdom of Poland alone, more than 200,000 young people were conscripted into the tsarist army in the years 1831/1832–1873. We still do not know the exact number of victims of this operation from the Borderlands. These horrifying statistics should give food for thought and be factored into the inconclusive argument about the price paid for independence, having a sovereign state and the point of the sacrifices made in successive uprisings. There is also a price paid for the lack of sovereignty…

It was even said to be the worst form of exile…

Well, yes, it was actually exile. Out of hundreds of thousands of people, only a few to a dozen percent returned. A huge majority (about 70%) died during this service. We should add that some of the former soldiers (20,000–25,000) remained in Russia because they had nowhere to return to after 20 years of absence. Only 20,000–25,000 made it home, while as many as 150,000 perished in the vastness of Russian Asia. They did not die on the battlefield but from the brutality of their commanders, disease or poor barrack conditions. These circumstances and experiences are unimaginable in this day and age. Besides, it was not only the Borderlands but also the Kingdom of Poland that operated on a similar, essentially colonial basis.

From Nicholas’s point of view, however, all these repressive measures were only the beginning of a long process of destroying the legacy of the First Republic spread out over a period of precisely 90 years. For this was the length of time that the Tsar gave the executors of his policy (such as the governor of the Kingdom, field marshal Ivan Paskevich) to fully ‘depolish’ the Borderlands and russify the Poles on the Vistula as well.

In the era of the ‘Paskevich Night’ and the post-uprising repressions beyond the Bug River, a completely new ideology, created at the behest of the Tsar, was taking shape in a clash with the strength of Polish patriotism. It was called the theory of ‘official nationality’. It was in fact the empire’s first official doctrine, a preparation commissioned by the throne. It was intended both to repel Polish aspirations to the so-called Western Russia and to stop ideological influences coming from Europe. The Polish uprisings and conspiracies represented both threats. This ideology was conservative and monarchical in nature, and its values were expressed by the slogans of ‘Tsarist autocracy, orthodoxy, narodnost’. The latter term was translated as ‘nationhood’ or ‘peoplehood’ in the sense of German volk or English ‘people’. These slogans were clearly a response to the Polish slogan ‘God, honour, fatherland’.

Alongside this official, conservative and monarchical ideology legitimising the reign over the Borderlands, new historical theories were being developed for the same purpose, also commissioned by the Tsar. The theory of Nicholas I’s court historian, Moscow University professor Nikolai Ustrialov, played a particularly important role. According to it, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was to be essentially a Russian state, the same as the Grand Duchy of Moscow. According to the view, which referred to ‘two Ruthenias/Russias’, there were supposed to be two Ruthenian/Russian states: the sovereign Muscovite Ruthenia, and the other, the Lithuanian one (the Grand Duchy of Lithuania) subordinated to Poland as a result of successive unions. In this perspective, the aggressive wars between Moscow and Russia were portrayed as a process of ‘gathering the Ruthenian lands’, only successfully concluded by the partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at the end of the 18th century. This allowed the ‘historical mistake’ to be rectified, i.e. to unite the two Ruthenian statehoods.

Unite under new slogans expressing the idea of a single ‘Ruthenian nation’?

Yes, it was also at that time that another, now renewed, idea of a great ‘triune Russian nation’ emerged, the constituent parts of which formed all the East Slavic communities, under the protection of the strongest, Great Russian. Today, this theory is experiencing its second youth. After two centuries, it has returned, to my amazement, to favour again. Now in a renewed form, as a justification for Russia’s contemporary claims to rule over the lands of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania, treated as the heart of the ‘Russian world’ (russkij mir). However, it was created a century and a half ago by the historians and ideologists of Nicholas I, not by some historical propaganda specialist of Vladimir Putin. It is important to note that with a similar justification for the rights to the eastern lands of the Republic, until the first half of the 19th century, Russia was still using mainly historical and religious categories. It was only in the 1830s-1840s, in the Nicholas era, after the November Uprising, under the influence of a new cultural trend, Romanticism, and with it, the development of ethnographic research that a different argumentation appeared, an ethnic one, referring to the category of language. The theory of the ‘triune Russian nation’ responded to this challenge by already applying not only historical arguments but also ethnic and linguistic criteria in the description.

It quickly gained the upper hand and was henceforth also used extensively in propaganda aimed at the European public in the mid-19th century to prove the Russian character of the Borderlands. This happened after losing the Crimean War, already after the death of Nicholas, in the era of the thaw and the triumph of liberalism in Russia. During the so-called ‘Great Reforms’, the most important of which was the abolition of serfdom, followed by the granting of freedom and land, questions arose: who were these peasants going to be especially on the borderlands, at the clashing point of Polish and Russian cultures? Who would they consider themselves to be? Would they become loyal citizens of Russia modernising under national slogans?

As a result, it led to rivalry with the Polish elite for the hearts and souls of the ‘Malorussian’ (Ukrainian), Belarusian, Lithuanian, Latvian and even Jewish populations. It became particularly evident in the era of the so-called ‘moral revolution’. It began with violently repressed demonstrations in the streets of Warsaw in February 1861, covering all the lands of the Commonwealth, beyond the Bug River, including Vilnius and Grodno, reaching as far as Kyiv. Polish initiatives under its influence manifested themselves in organic work, the establishment of illegal schools and the demands of landowners’ conventions to restore Vilnius University and the school district, as well as reinstate Polish-language education. It was all a matter of great dismay for the Russians, because in the wake of the reforms, of the liberal ideology of modernising the empire, a new phenomenon emerged at that time that is often overlooked in Polish historiography – modern, empire-centric Russian nationalism. The ‘liberal empire’ – a vision of new modernised Russia – presupposed that it was to become a nation-state, not just a tsarist monarchy. This was followed by a rivalry for influence over the millions of peasant minds and hearts called into civic life. The era of the January Uprising became the moment of dramatic confrontation against this background. From the Russian viewpoint, it was a battle for the Borderlands, for the West Country. Its preservation was seen as a prerequisite for the survival of the multi-ethnic empire and its ‘nationalisation’, i.e. its transformation into a national Russian state.

The fight took on particularly brutal forms for the time.

In spring 1863, Mikhail Muravyov ‘the Hangman’ – the new Governor General of Vilnius– stepped into action in Lithuania. His brutal methods of collective responsibility and lawlessness set new standards in the fight against the rebellion for a long time. However, Alexander II’s ‘liberal empire’ had tested other solutions before January 1863. At the time, several political movements can be distinguished in the Russian establishment, amid the growing crisis and the switching from repression to attempts to win over the Poles. The representatives of the old Nicholas regime were decidedly hostile to the Poles, but these were on the margins during an era of the triumph of liberal slogans. The aforementioned nationalist tendency, decidedly hostile to Polish aspirations, was increasingly strong in ‘Russia under reconstruction’. It demanded that the empire should cease to be the property of the Romanov family and the group of cosmopolitan elites associated with them. Instead, it should become the state of the Russian people. We also find this view among the so-called liberal bureaucrats, i.e. the higher imperial apparatus that actually implemented the great reforms on behalf of the Tsar. Their vision of modernised Russia was to preserve the system of self-rule and a centralised state as effective tools for modernisation against the interests of the nobility. Thus, these activists did not allow autonomous concepts for both the Polish population and the original members of the Ukrainian, Belorusian or Lithuanian intelligentsia. Particularly in the eastern lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth considered by all nationalists to be the cradle of Rus/Russia and the ‘Russian world’. The latter term was increasingly popular. At that time, a trend also emerged that rekindled hopes for the possibility of a return to some elements of the cultural autonomy of Alexander I’s time. It was represented by Minister of Internal Affairs Pyotr Valuyev, former governor of Courland, who proposed to base Tsarist autocracy on a consensus with the landowners’ community, including the okraina gentry. The minister even discussed similar projects with representatives of the Polish elite in 1861–1862, or at least, he allowed to officially submit such proposals to gain the Poles’ loyalty. While it raised hopes, it was, in fact, a delaying tactic in order to deflect the radicalising patriotic movement of the upper classes from the Borderlands. A number of similar requests were made by the Lithuanian and Belarusian gentry, less so of Ukrainian, because there was a noticeably lower Polish population. Also, the Russians were more sensitive just to the issue of ‘Malorussian’ separatism, as it was written at the time, considering it to be the result of a ‘Polish plot’. In the Lithuanian–Belarusian lands, the most active campaigner was the owner of the Strabla estate, located on the border with the Congress Kingdom (the palace has been preserved to this day) – Count Wiktor Starzeński, Marshal of the Gentry of Grodno Governorate. He tried to negotiate some (at least cultural and school) form of autonomy for the Northwestern Krai, as the official imperial nomenclature called the Lithuanian and Belarusian governorates. The ultimate plan was probably the administrative and legal separation of the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the form of an autonomy combined with an empire, along the lines of the Kingdom of Poland or Finland. Due to his political ambitions and strategy, Count Starzeński was called the ‘Lithuanian Wielopolski’. From the point of view of St Petersburg, the reforms of Margrave Aleksander Wielopolski proper, as head of the civil authorities of the Kingdom of Poland and executor of the conciliatory policy pursued on behalf of the new governor, the Tsar’s brother, Prince Konstantin, were to be confined only to the lands on the Vistula.

It seems to be often forgotten by historians disputing the purpose of Wielopolski’s reforms…

Even during the post-Sevastopol thaw that began after the defeat in the Crimean War in 1856, the Tsar – under pressure from Polish manifestations – allowed modest concessions from 1861 onwards. At the same time, however, he stood firm in declaring to the Lithuanian nobility in Vilnius: ‘Let them and Europe remember that here is not Poland’. Towards Lithuania, it was the equivalent of the famous words in French: point de rêveries (‘no illusions, gentlemen’) – words uttered to the Poles in Warsaw in 1856. There was no mention of major concessions beyond the Bug River.

Wielopolski understood these limitations very well. He was a ‘realist’. When opportunities of seeking concessions opened up in 1861 onwards, he adhered to the principle that the problem of ‘brothers beyond the Bug River’ should not be taken up, so as not to irritate the Russians. Therefore, by not raising the issue of the Borderlands, he effectively agreed to leave the fate of the Polish population in the east in the hands of the Russian administration. The long-term outcome, however, was the threat of their complete russification. All the more so considering that the alternative to the stance taken by Konstantin and Valuyev (who were seeking a consensus with the Polish elite on Russian terms) was a different scenario, already drawn out before 1863. It was represented by part of the aforementioned so-called liberal bureaucracy, i.e. a group of dignitaries entrusted by the tsar with reforming the empire. Unlike the noble liberals of the Valuyev type, who were willing to accommodate the interests of the old okraina social elites within a common conservative noble camp loyal to the monarch, they expressed a strong centralist, unificationist and nationalistic tendency at the same time. They followed the model of the authoritarian, populist Napoleonic monarchy of the Second Empire in France, proposing to base autocracy on a bureaucracy-controlled people. Admittedly, at this stage, the russification measures undertaken in this spirit were not carried out by methods as brutal as after the outbreak of the January Uprising. They were intended though as an effective way of pushing Polish influence out of the ‘eternally Russian lands’, which the ‘western governorates’ were considered to be. Set against the backdrop of the Russian elite’s discussion of the once again pressing question of ‘What to do with Poland’, there were then original solutions presented. In one of his articles, the eminent Lithuanian reasercher Darius Staliūnas aptly called them ‘affirmative action in the western borderlands of the empire’.

What did it entail?

The idea was to rely on Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian landowners loyal to the Tsar instead of concessions to Polishness in the form of a university in Vilnius, education or the restoration of nobility self-government. The tsarist administration’s reign was to be based on the local peasants, who were freed from serfdom and given land at that time. The intention was to grant them the right to use ‘peasant dialects’ – as their languages were called – by introducing them into the elementary education system, but under Russian control. At the same time, the identity and ‘dialects’ used by the inhabitants of the Lithuanian-Ruthenian lands were treated as an intermediate stage on the way to becoming ‘mature’ citizens of the empire, preferably Russians. It was assumed that for the time being, they could speak ‘peasant’ or even that ‘peasant schools’ should be established. However, their identity at a higher level of education was to be determined by the Russian language as a ticket to participation in universal culture. Accepting ‘regionalism’ at the local level but directed against the much stronger Polish identity associated with political aspirations for the restoration of the independent Republic, this agenda of gradual assimilation was put forward in particular by the Governor General of Vilnius, Vladimir Nazimov, who held this position before Muravyov. However, since an uprising had broken out, it was essential to put it down ruthlessly first. Nazimov was, therefore, replaced by General Muravyov. This was all the more so because in the spring and summer of 1863, there was widespread fear of war with the Western powers intervening, for the time being, only diplomatically in defence of the Poles. The Empire, which had not yet been able to finish any of the reforms it had undertaken, was well aware of the defeat in the Crimean War that had begun a decade before. Therefore, suppressing the protests in Lithuania and Belarus at all costs was intended to prevent the scenario of some sort of landing on the Baltic coast. Such concerns can be found in Russian military headquarters plans. Arguably, this was one of the sources of such a brutal crackdown launched by Muravyov in the spring of 1863, including the burning and deportation of entire parishes of the nobility, public executions and mass confiscations.

But it is also apparent that the uprising did not break out with equal intensity in all governorates and did not receive grassroots support everywhere…

Yes, of course. One significant difference may be observed between the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Ukraine, where the Polish side’s weakness was clearly visible. Here, Polishness was limited to the noble class, including the petty gentry. Meanwhile, in Catholic Lithuania, Samogitia and even in the western part of Belarus, the uprising took on a folk character. Therefore, the remembrance of 1863 has remained vivid here to this day, becoming, as in Poland, part of the historical identity of contemporary Lithuanians and Belarusians.

I was truly impressed by the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the January Uprising in 2013, which involved the Belarusian opposition. It is worth mentioning that in Poland at that time, in the era of the policy of ‘reset’ with Putin’s Russia, the official authorities flatly refused to patronise the commemoration of the anniversary of the uprising. The formal funeral of the remains of the Lithuanian and Belarusian uprising leaders executed by the Russians and buried in secret, which were found on Castle Hill in Vilnius, took place in 2019. These were heroes symbolising the last battle of the peoples of the Republic against the empire under the idea of rebuilding the common state. Among them were the remains of the war chief of the Kaunas Region, Zygmunt Sierakowski, who had been executed in Lukiškės Square, and the commissar for the National Government for Grodno voivodeship, Konstanty Kalinowski, who actually led the insurrection in the lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania since the summer of 1863. In fact, it was them who relied mainly on peasants and petty gentry, becoming the founding fathers of the modern national ideas of the inhabitants of the eastern lands of the former Polish Commonweath. (Father Antoni Mackiewicz should be mentioned in this context as well.)

In the Grodno region of Belarus, where many former Uniates either joined or supported the uprising, Belarusian historians calculate the participation of peasants in the uprising troops at as much as 25% to 30% of the total.

It should also be mentioned that in the 19th century, in both insurrections in the Borderlands, in addition to the strong Uniate tradition perceived by the Russian side as a threat that had to be dealt with, an important element was the significant presence of the population committed to the traditions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Polish language, Catholicism and Polish identity in the entire villages, hamlets and the so-called noble neighbourhoods. These were the aformentioned Bohatyrowicz family from the banks of the Niemen River eulogised by Orzeszkowa or Nadberezyńcy described in the novels by Florian Czarnyszewicz. In many cases, they were polonised, formerly Ruthenian, petty gentry – ‘boyars’, who had the same nobility rights as our ‘parochial’ people or ‘homesteaders’ from the borderland of Masovia and Podlasie.

How effective was the repressive policy? What was the Borderland community like at the turn of the 20th century?

For a very long time, our knowledge of russification or post-uprising repression was based mainly on diary sources. Too little use was made of the opening of post-Soviet archives for this era after 1991. A series of published studies and sources carried out in recent years by Prof. Stanisław Wiech of Kielce has brought about a huge advance in research. His findings provide a very clear indication of the successive stages of this policy. It was not only about the rich nobility but also about winning over the peasant population. Economic factors also played an important role in imperial strategies, e.g. the extreme taxes and tributes on a huge scale against the Polish population that were imposed for supporting the uprising. Prof. Wiech calculates that these fiscal burdens were much greater than we had previously imagined. Along with it, there was the difficult to imagine corruption and the ‘fight for land’. Beyond the Bug River, the involvement of some Poles, if only loyal ones, in the administration was abandoned. Finally, it was a matter of taking full control, including through education, of the consciousness of an increasingly subjective peasant population, by liquidating all Polish school institutions. When we talk about the ongoing processes over the course of the 19th century, we fail to notice the unbelievably drastic methods of repression, forgotten over time, that were obvious to people of that generation, such as the conscription of recruits described earlier. Such measures continued long after 1863, especially the martial law that was still maintained. The day-to-day reality for the inhabitants of the lands of the Russian Partition, especially the Borderlands, was therefore the prevailing military and police violence, giving free hand to the abuses of the corrupt tsarist administration. On the other hand, wziatki (bribes) were often the only means of rescue and mitigation of ironfisted repression. Moreover, the service in the western governorates attracted a specific human element – fanatical and looking to get rich quick… This experience of everyday violence gave rise to the anti-imperialist stance of the generation coming from the Borderlands, which was to renew active resistance at the end of the century, creating mass political movements demanding the restoration of an independent Poland. Józef Piłsudski, among others, belonged to this generation.

At this point, I would ask a question that probably cannot be answered: whose were the ‘Borderlands’ at the turn of the 20th century then? Polish? Russian? Belarusian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian? Did they belong to all of them?

The processes we have already discussed earlier resulted in profound social and ethnic changes in the lands of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. We must not forget it was an age of modernisation, the formation of modern national communities on the territory of the old multi-ethnic empires, whose identity was based on ethnic criteria in this part of Europe, followed by the manifestation of demands for political identity. Through these processes, the Russians attempted to manipulate the Lithuanians and Jews or to stop development of the Belarusians and Ukrainians. Since Belarusian or Ukrainian villagers were treated as part of the Russians, or at least as candidates to become Russians, their ethnic identity was usually not recorded in statistics, but only their Orthodox religion was stated. In order to assimilate, any Ukrainian or Belarusian educational activity was suppressed, seeing it as competition for the Russian identity or even a ‘Polish conspiracy’. In the case of the Lithuanians, on the other hand, the method of acculturation was applied by banning the so-called ‘Polish prints’, i.e. the Latin alphabet, until 1904. If someone wanted to publish in Lithuanian, they could only do so in Cyrillic. A similar idea was also trialled in Poland after the fall of the January Uprising: publication of around 100 schoolbooks for the country’s children printed in Polish using the Cyrillic alphabet. The identity of Poles as well as Lithuanians was saved by the Catholic Church. Polish peasants wanted to pray from prayer books in the Latin alphabet. Lithuanian prayer books and schoolbooks, also on the initiative of the clergy, were illegally printed in the Latin alphabet behind the cordon, in what was known as ‘little Lithuania’ – a patch of land under Prussian rule. From there, they were smuggled, sometimes with the help of Jewish smugglers, to the other side.

The Belarusian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian national movements developed between two very strong identities competing for the Borderlands throughout the 19th century: Polish and Russian. All officials and ideologists of Russian nationalism would have been able to repeat the words of Tsar Alexander quoted earlier in this era. Poles, on the other hand, until the 20th century, thought of these lands in terms of the historical heritage of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, i.e. within the borders of 1772. Otherwise, they would have recognised the partitions. The coming of age of the modern shape of the ‘successor nations’’ identity of the Republic, however, also posed the question for Poles: what is the future Poland to be like? The answer to this question was provided by new mass political movements spawned at the end of the 19th century. They took the shape of two programmes among Poles: one voiced by Piłsudski and the Polish Socialist Party, and the other by the National Democracy camp. The first one was of a federative nature, referring to the traditions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, considering the changes taking place in the development of identity. On the other hand, Roman Dmowski’s project was the vision of modern Poland just because nationalism was a thoroughly modern line at the time. The future democratic Poland was envisioned not so much as a mono-ethnic but rather as a unitary, nationally compact state, similar to France, as a unified republic dominated not by ethnic minorities but the Polish nation forming a modern state with its strong culture and language. In turn, the preservation of the ‘Borderlands’ and their ‘conversion’ into Russia was absolutely crucial from the point of view of the tsarist empire. While previously, the most important integrating factor of the empire was the monarchy and the Tsar, from the second half of the 19th century onwards, nationalist ideas determined that the Vilnius or Warsaw governorates were to undergo linguistic russification and be as Russian as Kursk or Moscow. This new nationalistic course officially began in the 1880s, since the reign of Alexander III. Paradoxically, it bore ‘poisoned fruit’ for the empire, as provinces hitherto loyal to it, such as Georgia, Armenia and Finland, the Baltic governorates, for example, were suddenly subjected to russification without reason, which until then had mainly affected Poles and the lands of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The result of this shift was that the russification policy – now extended to all the regions – led to an exacerbation of the imperial centre’s relations with all nationalities, even hitherto loyal ones. This became evident in 1905, rightly described as the Russian ‘Spring of Nations’, in which social demands merged along with national ones. The best example of this phenomenon was the data showing that the vast majority of death sentences for participation in the revolution concerned not Russia itself but actually okraina: from Finland to the Ukrainian lands and the Caucasus. They were much more active than Russia itself. Suffice it to say that as many as a quarter of the death sentences pronounced for participation in the 1905 revolution involved the inhabitants of the Kingdom of Poland, which, after all, was not very large, and 15% of those from the Baltic governorates. Thus, 1905 was not only a revolution of the Russians, but also of all the peoples living in the empire, including those in the Borderlands, foreshadowing what was to be repeated in 1917, after the Bolsheviks seized power. Then, after the Bolsheviks had broken up the democratically elected parliament (the Constituent Assembly), in January 1918, the periphery successively declared their independence. This phenomenon was to be repeated in the autumn of 1991 by way of acts of sovereignty expressed by the Soviet republics. It took place after the failed putsch in Moscow to save the USSR.

However, we must go back to the beginning of the 20th century. The Borderlands then fell – albeit briefly – into the clutches of somebody else.

The First World War broke out and a rival empire, Germany, entered the Borderlands. Influenced by nationalism, they attempted to carry out their own imperial project Mitteleuropa (Middle Europe) in the Intermarium. It involved the creation of economically and politically subordinate nation states. A renowed English research professor at Cambridge University (Senior Research Fellow, Trinity College), Dominic Lieven, in an excellent piece of work published in 2015, Towards the Flame: Empire, War and the End of Tsarist Russia, goes as far as to argue that it was the battle of the empires over Eastern Europe (especially the lands and assets of Ukraine rather than the Balkans) that was the main cause of the First World War. The defeat of the Russian Tsar created an opportunity for many national movements. Their activists tried to establish cooperation with Germany by proclaiming the sovereignty or ‘semi-sovereignty’ of their countries under the protectorate of the German Kaiser. Berlin attempted to incorporate these tendencies to carve out new states on the territories of the Russian empire into its geopolitical plan of Mitteleuropa, most fully described in Friedrich Naumann’s book published in 1915. It entailed German political, economic and cultural hegemony over the entire Intermarium. The German loss in the war made their project of a land empire in Central and Eastern Europe obsolete for a while. After two decades, Germany was to return to this plan with a criminal, racist ideology under the banner and with the help of genocidal policies of the Nazi party. With the totalitarian methods, they attempted to realise the same geopolitical project under the slogan of Lebensraum (living space). With results we know all too well… The land between the so-called geopolitical Smolensk Gate and the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin became in the 20th century the area of the highest intensity of atrocities, totalitarian experiments to build a utopian ‘Kingdom of God on earth’, which soon turned out to be a real ‘Satan’s training ground’ – a place of genocide. After all, this was the area where the world’s first totalitarian system was created. (We can call it ‘Slavic’.) Its effectiveness became a model for other similar totalitarian regimes, successively in Italy and Germany, although preaching against it.

The conquest of the lands situated on the continental bridge between the Baltic and the Black Sea also renewed their geopolitical importance. It was the eternal East–West route. However, when the Bolsheviks were stopped on the Vistula and then on the Niemen River in 1920, they had to concentrate on organising the empire that was given to them. In fact, one could quote the renowned American revolutionary historian Richard Pipes to the effect that the Bolsheviks carried out a ‘red reconquista’, i.e. that they brought back together the empire of the tsars, which had completely disintegrated between 1917 and 1918. Their main challenge was to maintain the recovered okraina and their precious economic and human resources. The new regime’s future depended on it. The solution was to take a step backwards, i.e. to annouce the so-called NEP – New Economic Policy. It marked a retreat from the plundering and violent methods of war communism and the most insane economic experiments in order to maintain power. Now, in dealing with the rebellious population of the peasants, compulsory quotas were replaced by a food tax.

Two years later, in 1923, another policy was introduced, dare I say ‘the ethnic NEP’. Such an acronym, in any case, can be formed from the term ‘new ethnic policy’. It involved what came to be known as korenizatsiia (‘indigenisation’ or ‘nativisation’) – an attempt to ‘root’ communism in okraina through a system of cultural autonomy granted to non-Russian peoples. It was not because the Russian Bolsheviks suddenly believed that they had to be given real freedom to develop, but because they had very little influence in these lands. They won over the ‘whites’ here, promising self-determination to nations on the periphery. The socialist intelligentsia could have been a partner here. However, it was not Bolshevik. It combined ideas of ‘progress’ with slogans of national autonomy. Therefore, the demands of the left-wing elites of the okraina nations were met, education in national languages and autonomy were allowed.

Prior to the revolution, in 1913, the Bolshevik party (with the direct involvement of Lenin and Stalin) had created a theoretical construct (developed during the two leaders’ stay in Cracow and Vienna) in which national demands were to be subordinated to the class interests represented by the Bolshevik revolutionary party. Once in power, as part of the system of Soviet federalism of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics proclaimed at the end of 1922, a whole, huge, hierarchical pyramid of autonomy was built up, starting from the status of an autonomous republic to local self-government at the level of villages. The Soviet Ukraine and Belarusia were the prime examples of this system. The manifestation of this stage of the sovietisation policy, implemented through national languages and cultures as allowed, became ‘ukrainisation’ and ‘belorutenisation’ in the cultural and educational fields. Of course, the culmination of all this was the pseudo-federal structure of the USSR. From behind this façade, however, the Communist Party along with its subordinate administration, and above all the secret police: the Cheka, GPU, OGPU and then NKVD, ruled with a firm hand. Under the policy of korenizatsiia, which lasted until 1929, until the official replacement of the NEP with a programme of increased industrialisation in the form of five years, a whole class of Ukrainian, Belarusian but also of other nationalities intelligentsia emerged.

As a reminder, during the revolution, Joseph Stalin was the People’s Commissar of Nationalities and preached slogans to win over Islamic peoples, for example, by accepting Sharia, which he praised as ‘progressive’. In the Eastern areas, where there was no proletariat, but instead a colonial type conflict, the Bolsheviks appealed to ethnic and racial division, i.e. to the slogans of the battle of the Asian natives against the white colonisers, especially Britain considered the main enemy of the USSR. Asian nations, especially Muslim ones, were to become a transmission belt for the transfer of the communist revolution under the slogans of the fight against European domination. With such anti-colonial slogans, the Bolsheviks carried out communist propaganda in Iran, Central Asia, India, collaborated with the nationalist Young Turk movement who, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, took control of the remnants of the Ottoman Empire, entered civil war-ridden China… Korenizatsiia was just an element of this broader policy of preparing east–west export of the revolution. It concerned a particularly vulnerable border in Eastern Europe. Confronted with a reborn Poland, against the backdrop of the Belarusian and Ukrainian question, Moscow organised and routed communist partisans attacking the eastern provinces of the Second Polish Republic in order to destabilise ethnic relations. In the background was the Soviet collaboration with Germany and the attempt to respond to Polish Prometheism, i.e. the idea of supporting the independence movements of the peoples of the Soviet empire.

As part of the policy of korenizatsiia, it was against the background of this game that the two autonomous regions were created in the Soviet part of the Borderlands – Marchlewszczyzna in Ukraine (from the mid-1920s) and Dzierżyńszczyzna (in 1932) in Belarus. There were also plans to establish other autonomous units on the Dnieper (Dnipro area) or in Podolia. The whole project of Polish autonomy was subordinated to geopolitical plans to move the revolution westwards, which required the destruction of the Second Polish Republic. The idea was to raise subordinate Polish, Ukrainian or Belarusian communist cadres to the Bolsheviks, and a ‘new Soviet citizen’ to carry the revolution beyond the borders of the USSR. The experiment to re-educate the Poles was to be conducted through a new proletarian culture. An attempt was made to break with the old identity, culture and its symbols, even changing the spelling of the alphabet, and especially fighting religion – Catholicism – called the ‘Polish faith’. The Poles, however, proved exceptionally resistant compared to other nations. The Polish experiment ended in complete failure. Suffice it to say that even the local cadres of the Communist Party and Komsomol had to be staffed with people brought in from the big cities, émigrés from the Polish Communist Party or representatives of other ethnic groups ‘performing the duties of Poles’…

So the time has come for another change of strategy…

Soon the whole strategy of korenizatsiia was lost along with Trotsky’s defeat and his programme of ‘permanent revolution’ in the second half of the 1920s. The ‘export of the revolution’ was temporarily postponed. Stalin announced a plan to build ‘communism in one country’, which was to be expressed in the creation of heavy industry subordinated to the goals of arms industry. To this day, the naïve view of the supposed abandonment of the expansion plans persists – the view of tractors or power stations rather than aircraft and tanks. In fact, the entire programme of accelerated modernisation of the USSR served to prepare for a future offensive war. Stalin did not give up his global goals of revolution. He simply changed the tactics and intended to rely on his own army and potential instead of fuelling the hitherto effective, chaotic attempts to trigger provoke revolution and communist uprisings. The ‘Stalinist revolution’ (the dictator’s own term) was to mobilise resources. What it meant was a return to the methods of mass violence of the revolutionary and civil war periods in order to forcefully compel the whole of society to work towards set global goals.

But how was he supposed to finance such ambitious projects in an underdeveloped country devastated by revolution and civil war, with no capital of his own and no chance of borrowing (except from Germany)? The only resources left to the Bolsheviks after squandering the plundered treasures of the tsars and the Orthodox churches, under the guise of raising funds to fight famine in the early 1920s, were people and land. Therefore, it was necessary to apply the economic system that Karl Marx, the classic of communist ideology, called ‘primordial accumulation’, which was effectively plunder. This was reminiscent of the feudal methods of the pre-modern Moscow and Russian empires. The citizens of the USSR were the victims of such autarkical modernisation. Acquiring the necessary capital was to be done at the expense of the countryside, where 80% of the population lived. This was to be done by creating a system of forced labour and taking back control of food production and land. The villagers, especially in the non-Russian areas, were henceforth to produce food for the planned economy in collectivised farms, under the control of the Soviet administration, and to provide a slave labour force. Admittedly, this ‘army of labour’ was, in fact, invented by Trotsky in order to man the great construction sites of socialism. This programme was carried out by his mortal enemy, Stalin.

To this end, the great collectivisation operation carried out at the turn of the 1920s/30s led to a terrible famine. This, particularly in Ukraine, the southern governorates of Russia and Kazakhstan, was artificially induced in order to break the desperate opposition of the peasantry.. It turned out that the greatest resistance came from communities living in the western periphery: Ukrainian and Polish peasants. The operation was much more easily carried out in Russia itself. To some extent, the difference was due to the tradition of private land cultivation in the lands of the former Commonwealth. In Russia, rural communities (mir, obshchina), had collectively owned cultivated land for centuries, a practice that was maintained after the liberation of the peasants in 1861. Despite Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin’s reforms after the 1905 revolution and the formal dissolution of the communities to open up the possibility of colonising Russian Asia, especially the steppes, most of the peasantry continued to farm in the old way.

Statistics from the implementation of forced land expropriation poured onto Stalin’s desk. Some historians even see him as a murderer ‘from behind the desk’. He certainly saw that the greatest resistance from the rural population was noted in the western areas. This began preparations for the gradual phasing out of autonomy. What followed were further deportations from the border area in the 1930s. This was due to the dynamically changing international situation, especially after Hitler came to power in 1933 and broke off the cooperation with the USSR, which had been so close since the Rapallo Agreement in 1922. There was also a growing threat from Japan in the Far East. Poland signed non-aggression pacts with the Soviets in 1932 and with the Third Reich in 1934, pursuing a ‘policy of balance’. For Stalin, however, this foreshadowed the Polish-German alliance. To this day, the lie about the alleged secret ‘Piłsudski–Hitler Pact’, which never existed, is being renewed by Putin’s propaganda. However, this legend was created by Stalin’s propaganda in order to accuse Poland of alleged collaboration with Germany and to justify the later real Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

So Poland and Germany, and by extension the Soviet citizens of these respective peoples, became at this point the main enemies of Soviet power?

In this situation, all of the nations that represented ‘external enemies’ in the eyes of the Soviet authorities became particularly suspect. These included Germans (a large group of whom had lived along the Volga and in Ukraine since the 18th century) and Poles. In the Far East, a similar role was played by those peoples and groups who, in Stalin’s imagination, represented Japan’s interests, namely the Koreans and the so-called Harbiners, mainly ‘white’ Russians who had worked on the East China Railway built by Russia in Manchuria near Harbin and who were allowed to return to the USSR. In the perspective of the future war for which they were preparing, they were all seen as a ‘fifth column’. In Stalin’s mind, it justified the need for an operation to destroy a potential living ‘recruiting base’ of foreign intelligence. A memento for Stalin was the situation in civil war-ridden Spain. At the very least, it meant condemning men to extermination regarded as a ‘human resource’ that the enemies of the Soviet Union could potentially exploit. In practice, it meant the destruction of an entire ethnic group, representing, in the imagination of Stalin and his subordinate authorities, enemy states. This is the genesis of a series of a dozen ethnic operations, with the bloodiest ‘Polish’ at the forefront, carried out at the apogee of the Great Terror in 1937–1938. It was the suspected peoples who provided the greatest number of victims, alongside the so-called kulaks, the survivors of the rural elite, and not, as once thought, the party elite. The Great Terror itself, on the other hand, was a precisely planned and executed series of genocidal acts carried out against its own citizens, under peaceful conditions, at the behest of the legitimate, internationally recognised, never punished authorities of the USSR…

The most cruel of these operations affected the Poles. Koreans were ‘only’ deported from the Far East to the steppes of Kazakhstan. Even the Germans did not experience such a scale of crimes as the Poles, especially from the so-called ‘further Borderlands’, i.e. the eastern lands of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that remained on the Soviet side of the ‘Riga’ border. The origin of those arrested was determined by their Catholic faith, language or even the sound of their surname. The victims were usually men aged between 16 and 60. Out of 100 detainees, more than 80 were usually murdered, and in western Siberia as many as 95.

To this day, it is difficult to calculate the true scale of this atrocity, which involved the physical liquidation of entire social groups representing continuity with the heritage of the First Republic. The official NKVD censuses mentioning more than 111,000 victims are a minimum figure, but closer to reality, it probably exceeds 200,000. According to the NKVD statistics known so far, during the Great Terror in 1937–1938, at least around 1.5 million people were arrested, 681,000 of whom were murdered. In this death pool, kulaks and representatives of national minorities accounted for as many as 625,000. A total of 247,000 executions were the result of operations against nationalities, mainly Poles.

Thus, minorities constituting only 1.6% of the population provided as much as 36% of the total number of victims of the Great Terror. It was the Poles, however, who were the most persecuted, on average several times more likely to become victims of crime than other nationalities, and in Leningrad, for example, more than 30 times more likely than Russians. The brutality and unique nature of this genocidal operation is evidenced by the fact that for these huge numbers of convicted by the extraordinary extrajudicially acting so-called ‘twos’ and then ‘threes’ made up of the local heads of the NKVD and the prosecutor’s office and the Communist Party, in addition to the already cruel Soviet law, there were only a few cases of acquittals. We should add that the victims of the ‘kulak operation’ had a one-in-two chance of being sent to the Gulag, and therefore some hope of survival. Meanwhile, victims of the anti-Polish operation were murdered in three out of four cases.

Horrifying. But we are talking here about internal politics across the empire. And what about the Borderlands?

The intensity of these crimes proved to be highest exactly in the areas of the former Borderlands, Ukraine and Belarus, subjected to constant mass repression and starvation in the 1930s. Whatever the discrepancies in numbers, the effects of this crime meant the physical destruction of the Polish community in the USSR, especially in the lands of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This monstrous genocidal crackdown on Poles is incomparable in scale to anything else, with the possible exception of the ‘Greek operation’. Although the Greeks were very few in number, and we still cannot count the Poles. And the worst thing is that until recently this crime was almost non-existent in Polish historical memory or in the consciousness of even those interested in history, not to mention public opinion or researchers outside of Poland. And it was the largest ethnically motivated massacre in the first half of the 20th century, between the massacre of the Armenians and the Holocaust. It was also a totalitarian in form, following the old programme of ‘cleansing’ the Borderlands.

Looking at the causes of the extermination of Poles across the Riga border, let us emphasise once again that the key moment, in which the class context was translated into an ethnic one, and Poles were cast in the role of the Soviet state’s greatest enemy, was the failure of the experiment of sovietisation by means of korienisatiia and the period of collectivisation. Then overlaid with this was the growing threat of war with the ‘fascist states’, which of course included the Second Republic led by Piłsudski. It was probably then that all these factors converged in Stalin’s imagination.

The consequences of this never-punished crime of ethnic genocide are difficult to overstate. The methods which were used to dispose of the Poles after 17th September 1939 in the other parts of the Borderlands as well as the cruelty of the well-known ‘Katyń Operation’ stem from these two years earlier experiences and the modus operandi of the ‘Polish Operation’ of 1937–1938. It was a transpositon of the scenarios and methods of mass crimes (and sometimes also of their executors) from the period of the Great Terror to the other side of the Riga border which divided the former eastern territories of the Republic of Poland. This new wave of genocidal operations was sometimes carried out by the same officials, such as Lubyanka commandant Vasily Blokhin – Stalin’s favourite executioner – who had a magnificent tombstone erected in Moscow’s Novodevichy Cemetery (not far from the mass graves of his victims or rather death pits into which their cremated ashes were dumped). This was an officer who single-handedly killed at least 10,000–15,000 people. On Stalin’s orders, he executed his former boss Nikolai Yezhov, who had been made responsible for the Great Terror. He then carried out a sizable part of the ‘Katyń Operation’ in Tver (at the time Kalinin), where, in the basements of NKVD, he single-handedly murdered Polish officers, using the so-called Katyń method. In essence, the same method used two years prior, during the Great Terror.

This ongoing series of blood crimes was disrupted by the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941. However, as soon as the Red Army took the initiative at the front, Stalin resumed the policy he had pursued.

The same methods of disintegration by genocide and deportation, already proven in the 1930s, were also used in the case of the ‘punished peoples’, who were suspected during the Second World War not even of actual collaboration but of a mere desire to cooperate with the Germans: the Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Crimean Tatars, Meskhetian Turks. Eastern Europe on the land bridge between the Baltic and the Black Sea, together with the former Borderlands, came back under Stalin’s rule in 1944. These were those ‘Bloodlands’ (as the American scholar Timothy Snyder described them in the title of his work) massacred by the genocidal experiments of the two totalitarian rivals for control of the Intermarium, the Soviet and Nazi empires. After the return of the Red Army and NKVD, their inhabitants again suffered a wave of repression, zachistka (cleansing operation) and deportation. Actions such as the Augustów Round-up in July 1945 can be considered the symbolic culmination of these methods of pacifying the western borderlands of the Soviet empire carried out on the territory of post-Yalta ‘people’s’ Poland. The bodies of the victims murdered then – or rather the place where they were abandoned – are yet to be found. After all, the same methods and operatives, usually well-tested as far back as the 1930s, were behind it. These things came out of the experience of the atrocious crackdown on border peoples and ‘kulaks’, expecially in the ‘further Borderlands’ before 1939.

We might want to add that the policy regarding the Borderlands, the attempt to unite all territories inhabited by Belarusians and Ukrainians, grew out of Stalin’s geopolitical vision: the acquisition of all East Slavic lands. This concept, in fact, was shaped largely under the influence of Russia’s imperial heritage. This is what Stalin called upon – as a new ideological bonding agent – when ‘nationalising’ Soviet communism in the 1930s as a new legitimisation of dictorial power and its global goals. Stalin’s introverted nature has made it difficult to reconstruct his actual plans to this day. We are more able to reconstruct these from deeds than words.

A characteristic anecdote was saved by Vyacheslav Molotov, one of the most dedicated and closest co-workers of the ‘Stalin team’, the long-time head of Soviet foreign policy. He described seeing Stalin in the Kremlin after the Second War, at some leisure moment, pondering the course of his empire’s borders with the pipe’s cigarette butt. He clearly wanted to return to the shape of Russia as it was in 1914, i.e. to fulfil the geopolitical ambitions of the tsarist state. What comes to mind here is a map issued by the General Staff of the Tsar’s army in 1915, presenting a vision of future Europe. Its stipulated shape was remarkably similar to the one given to post-Yalta Eastern Europe after 1945. Russia’s borders drawn in 1915 were to reach the Baltic and the Oder, albeit without the Lusatian Neisse, which Stalin invented ad hoc in order to move Poland westwards. It was thus a vision of the whole of Central and Eastern Europe, together with the Balkans, dominated by the Russian empire ruling here directly or through vassalised nation states. The continuity of geopolitical thinking about the role of the Intermarium, of which the Borderlands were the key, went beyond ideological boundaries, linking the geopolitics of the two empires. Sadly, what we see in Russia today is a deliberate reference to both versions of this imperial tradition and ideology in the ‘white’ and ‘red’ editions. It is worth bearing in mind that the geopolitical imagination of today’s Putinist Russian elite grows precisely out of this deep, never-accounted-for and never-rejected imperial legacy…

Dr hab. Henryk Głębocki – a scholar of the Eastern European history, the Russian and Soviet empires and Poland of the 19th–20th centuries. He is a lecturer at the Jagiellonian University. At the same time, he contributes to source editions for the Historical Research Office of the Institute of National Rememberance. His books have recently been published as a result of his research into the history of the Polish–Russian conflict in the 19th and 20th centuries, among them: Jak nie dać się ‘strawić’ imperium? Polacy ‘połknięci przez Rosję’ – postawy, idee, strategie (1814–1914), Cracow 2023; Między ugodą a resurekcją: granice polsko–rosyjskiego kompromisu politycznego w epoce Królestwa Polskiego 1815–1830: materialy z konferencji naukowej zorganizowanej w 190. rocznicę koronacji 1829 roku (24 maja 2019) edited by H. Głębocki, Warsaw 2023; H. Głębocki, A. Barańska, M.Kulik (eds.), Towarzystwo Patriotyczne oraz tak zwany spisek koronacyjny 1829, Warsaw 2023; Adam Gurowski, Wybór pism, t. 1, Filozofia historii i cywilizacji, edited by H. Głębocki, Warsaw 2022; A Disastrous Matter. The Polish Question in the Russian Political Thought and Discourse of the Great Reform Age, 1856–1866, Cracow 2023.

Translated by Małgorzata Giełzakowska