Yevhenii Monastyrskyi

In April 2024, 161 children deported by Russians from Ukraine were found in Germany. We don’t know for sure how these children ended up in the European Union, but there’s an important detail in this story that’s been overlooked by major international news outlets. Amidst global war fatigue, media coverage often neglects the ongoing brutality faced by Ukrainians in occupied regions. Yet, tragedies like these persist as a sobering reminder of ongoing crimes that demand our vigilant response.

Such events are a stark reminder of the relentless war crimes committed by Russia in Ukraine, compelling deeper reflection on their heinous actions over the decades and centuries. These children’s story, however, weaves a somber web from threads of past and present conflicts, mirroring the harrowing experiences of countless Ukrainians deported by the Soviet Union. In examining the past and present of deportations in Ukraine within this brief format, I will focus on two aspects that have accompanied and continue to accompany the forcible displacement of populations by Russians: power and ownership. By displacing people, separating parents from children, subjecting Ukrainians to humiliating filtration procedures and compelling them to accept Russian citizenship, Russia not only imposes its dominion but also enacts a form of appropriation, transforming individuals into objects of control and ownership. This underscores not merely a desire to govern territory but a deeper ambition to possess the lives and identities of its inhabitants, showcasing an absolute form of power that permeates all aspects of existence within occupied communities.

Deportations as Exercise of Power

Forcible population displacement is nothing new to Russia or the rest of the world. It was part of the Soviet Union’s toolkit throughout the time of its existence. There were three main reasons for Soviet deportations from Ukraine: the first was class-based, which meant mass expulsions of people based on their social origins; the second was deportations based on ethnicity; the third was political, which meant political cleansing of border areas of national groups the authorities distrusted. The “kulak expulsions” in the 1930s and 1940s and the expulsion of Crimean Tatars, Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Poles, and Germans from border regions are notable instances of such deportations from Ukraine. Historian of Soviet national policy Terry Martin made a compelling case that this practice, which was pervasive throughout the USSR, was essentially “ethnic cleansing” rather than just deportation.

A major component of the Soviet project’s social and political construction was the exercise of power through the cleansing of territories and entire regions. As part of their plan to establish multiple national regions, the Bolsheviks actively courted members of minority ethnic groups, going so far as to extend invitations to emigrants from other countries; for example, Finns were brought from the United States and Canada to Soviet Karelia, where they could help build national regions based on the Piedmont principle. In addition to being a form of punishment based on the idea of class and “class struggle”, deportations were also a means of exerting control over the populace in order to bring about the desired change.

Not increasing the number of Ukrainians living in the republic but removing “class enemies” and “potential traitors” from the borderlands was the real goal of deportations in twentieth-century Ukraine. Thus, deportations were a biopolitical tactic used by the Soviet regime to manage and organize human life so that it conformed to socialist state ideals.

The regime’s use of population displacement and subsequent resettlement allowed it to exert biopower by controlling its subjects through monitoring, normalization, and regulation; this allowed it to eliminate potential dangers and enforce conformity. Part of the Soviet goal in building a socialist state was biopolitical population control, which shows how power can be exerted not only by openly repressing people but also by subtly regulating and manipulating their lives. In other words, the Soviet state’s strategy of engineering a social order that conformed to its ideological blueprint was reflected in the deportations from Ukraine; these were an expression of its power and were intended to rid the republic of elements the regime deemed undesirable or dangerous.

Simultaneously, during the interwar period the Soviet authorities relied on primordial notions of nations and national territories to exercise their power and implement their designs. However, the onset of World War II introduced a new dimension to ethnic cleansing: the systematic deportation of indigenous populations labelled as potential traitors or class enemies, with the aim of consolidating the regime. This new dimension was defined by the deliberate selection of entire ethnic groups for expulsion, not solely for the purpose of social or political control, but as a means of homogenizing the population and eradicating any perceived risks to the stability and security of the Soviet state, whether stemming from the diverse ethnic composition or the Soviets’ lack of trust in the local populations.

In the current Russian-Ukrainian war, deportations echo practices from the Soviet wartime and postwar reconstruction periods, utilizing deportation in two manifestations of power: as forced “evacuations” of populations purportedly from conflict zones, or as the cleansing of territories of local inhabitants to resettle them with more “reliable” populations. Forced evacuation, in reality, is a concealed form of deportation, as forced displacement of populations can only be considered evacuation under international law if it is necessitated by safety concerns and has valid reasons; moreover, people must be relocated within the borders of their own country. By displacing Ukrainians from their homes, the Russian occupation administration has also initiated a reverse movement, bringing Russian citizens into occupied Ukrainian territories. This practice is reminiscent of the Soviet strategy of resettling demobilized Red Army soldiers in border areas that had just been “cleansed” of the local population – disloyal populations were replaced with loyal ones. According to some Ukrainian officials, approximately 40,000 Russians have already been resettled in Mariupol, and numerous online video tours by real estate agents showcase destroyed apartments whose owners have either been deported, managed to escape to territories controlled by the Ukrainian government, or perished during the siege of the city.

Forced evacuation as a practice of power not only illustrates the imposition of control but also reveals a deeper strategy of ownership and population replacement. This form of population management reflects an enduring legacy of Soviet-era policies, where the movement of people was instrumental in asserting state power and reshaping demographic realities to align with the occupying power’s strategic objectives. Thus, the current deportations are not merely acts of displacement but are integral to a broader scheme of territorial and demographic engineering aimed at solidifying control and ensuring the subjugation of the occupied regions and their integration into the Russian state apparatus.

Occupation and Deportations as Ownership Practice

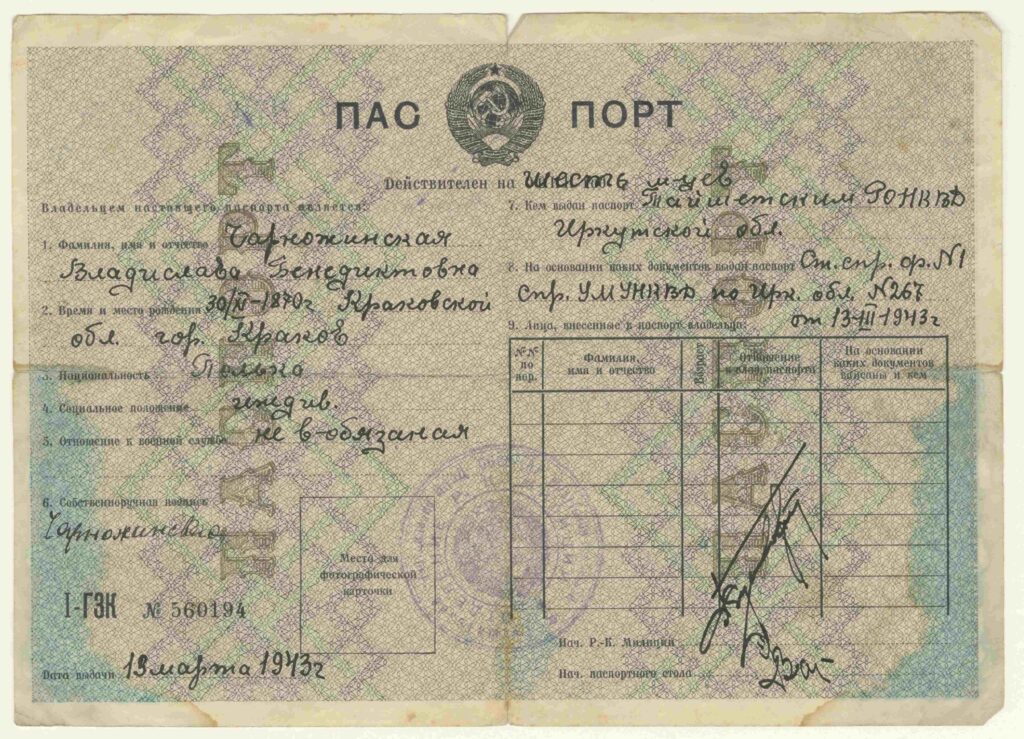

The Soviet government began a slow but steady process of forcing foreigners in the USSR as political migrants or labourers to become Soviet citizens in the mid-1930s. The stated goal of this practice was to assert Soviet ownership of specialists by preventing their free departure and by establishing full legal control over them. It is well-known that becoming a Soviet citizen left these foreigners open to terror, as it is easier to carry out extrajudicial actions against one’s own citizens than against foreigners. This method, which has been carried over into Russia’s current deportation repertoire, eventually became a pillar of Soviet power. Accepting Russian citizenship is now a requirement for surviving in occupied territories, which includes avoiding deportation, losing property, and, worst of all, losing one’s own children. Be that as it may, Russia started using these tactics before 2022.

Since 2014, following the occupation of parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions and the annexation of Crimea, Russia has exerted its power over the inhabitants of these territories primarily through various restrictions. The occupying authorities have curtailed freedom of movement and access to social and medical services, fostering an atmosphere of life-threatening danger. From 2014 to 2022, there were no documented cases of forced deportations from these occupied areas. However, conditions were created that made it untenable for Ukrainian citizens to remain in their homes. Residents of larger cities were acutely aware of extrajudicial arrests and torture of their compatriots in the basements of administrative buildings and special torture prisons, such as the notorious “Izolyatsia” in Donetsk, vividly detailed in books by journalist Stanislav Aseyev, who spent over three years there. Ultimately, the occupation fostered a situation where individuals had to either submit to the new order or become targets for Russian security services.

This subjugation was enforced not only through the suppression of dissent. The principal manifestation of this control was the imposition of Russian citizenship. In Crimea, acquiring citizenship quickly became mandatory, blatantly signifying direct and effective control not only over the territory but also over the people: they were now the property of the occupying state, subject to its legal system and mechanisms of control, rather than international law. In the occupied territories of Luhansk and Donetsk, this practice evolved into a ritual of humiliation: by not officially recognizing their presence, Russia initially refrained from openly distributing passports, focusing this subjugation primarily on local authorities. Ordinary people were made to acquire citizenship of the self-proclaimed republics; to obtain a Russian passport, they had to travel to Rostov-on-Don, enduring a long and humiliating process. With the onset of the new phase of the Russian-Ukrainian war in 2022, obtaining citizenship became a compulsory procedure in the occupied territories, especially those occupied since 2014. Now, without Russian citizenship, individuals are not only restricted in their rights but also gradually lose access to state and medical services.

Another ownership practice is the so-called “filtration camps”, which are essentially special checkpoints through which everyone attempting to leave war-torn cities must pass. The filtration camps through which residents of Mariupol, attempting to escape the besieged city where thousands of civilians were dying daily, became notorious. According to testimonies, the filtration process is a degrading procedure, involving stripping, interrogation, and thorough checks of all phone data. This filtration practice also threatens violence against Ukrainians, particularly if they do not show deference to the representatives of the occupying authorities.

The very term “filtration” is a claim to power and, by extension, ownership. The two main manifestations of this action are the initial deportation of individuals registered in territories occupied since 2014 (for instance, internally displaced persons from Donetsk or Luhansk who have fled to Melitopol) and the forced separation of children from their parents. Those who have made it through the ordeal say that it is standard practice to immediately transfer Ukrainian nationals found to be registered in the puppet republics’ territory to the occupation administration’s prison system in either Luhansk or Donetsk. This means that most of these people aren’t just sent back to their home countries: they’re labelled “enemies of the people” and sent to special prisons and camps. Registration in occupied territory refers to the old Soviet practice of “propiska”, a system that rigidly attaches a person to a specific address. Unlike registration practices in other countries, “propiska” in the Soviet and post-Soviet context involves a complex and bureaucratic process requiring numerous documents to register or change one’s address. This system creates a bureaucratic stalemate for those registered in areas controlled by Russia’s puppet republics as they cannot easily change their registration, and the state is unable to accommodate registration changes for millions of people. In this way, a system of dual ownership is in place: when a person is registered in an occupied territory, this confirms not only Russia’s ownership over them but also the administration of those territories, which often treats people they perceive as “traitors” more harshly. This dual ownership system exacerbates the situation, leading to harsher treatment and stricter controls over individuals labelled as potential threats.

Apart from that, there are many stories about how parents and children were separated during “filtration”. Investigators and Ukrainian officials have highlighted cases where children who have been returned from Russia testified that their parents were forcibly removed from them and placed in special camps far from war zones. The next step was to inform the children that their parents had left them and would not be coming back. The children were led to believe that no one would come looking for them. Subsequently, reports indicate that children from Ukraine were separated and sent to different regions of Russia in an effort to prevent them talking to each other and hasten their integration into Russian society.

The expedited adoption program for children in Ukraine is another way that parents show their ownership over their children. Children who have been filtered – separated from their families and homes – are handed over to Russian families in a specific sequence – humiliated and devoid of dignity. Orphans whose homes are located on occupied territories face a similar predicament; this practice has been commonplace since 2014. Russia made it easier to adopt Ukrainian children who were deported at the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022 so that this could happen. Now, this all happens in secret court sessions; once a child is adopted by Russian citizens, they can get a new name, which makes it very difficult to track them down and bring them back to Ukraine. Estimates of the number of deported children vary from 20,000 to 400,000, making it impossible to know for sure how many deported children there are. Just over 400 children have been repatriated to Ukraine thus far.

Appropriation practices are getting worse. Refusing Russian citizenship is a systematic way to restrict access to vital services in occupied territories, including the denial of insulin for diabetics. This restriction has been in place since 2014. Legislation allowing the deportation of Ukrainians who refuse Russian citizenship after heavy fines is reportedly about to be enforced in the occupied territories. To make matters worse for the millions of Ukrainians living under occupation, in May 2023 the Russian Federation’s State Duma passed a law allowing the free deportation of anyone from war zones without their consent.

Even now, nobody knows for sure how many Ukrainians have been deported. As of the end of 2022, according to Dmitry Lubinets, the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights, 2.8 million Ukrainians had been deported; in 2023, Russian officials claimed that 4.8 million Ukrainian citizens, including 700,000 children, had been deported to Russia. It is uncertain how many more will be coerced into becoming Russian citizens and assimilating into far-flung regions of Russia, so the exact magnitude of this tragedy will be unknown for some time.

The occupying authorities are actively claiming ownership of the lives and identities of the occupied population by implementing measures such as Russian citizenship enforcement, filtration procedures, and child abduction. This strategy is part of a larger effort to subjugate the occupied territories and their people by making their control an integral part of daily life. The goal is to assimilate them into the Russian state apparatus and erase any remnants of previous identities and loyalties in favor of the new order.

Yevhenii Monastyrskyi is a PhD candidate at Harvard University, specialising in Eastern European history. He holds degrees from Ukrainian Catholic University and Yale University (European and Russian Studies). He is a Principal Researcher at the War Childhood Museum (Ukraine) and a lecturer at the Kyiv School of Economics.