Marta Herling

In Gustaw Herling’s archive, a letter written by him to Ostap Ortwin has been preserved, sent from the Gulag in Yercevo in the Arkhangelsk region. It is undated, although it was penned in the winter of 1940.

Gracious sir, I promised myself that I would write to you after my arrival in Grodno. Not only to thank you so very much for everything you did for me in Lviv; but also to engage you from a distance, in a conversation about poetry. I know very well how poetry lovers value such dialogues. It is not surprising then, that the temptation was hardly a small one. Unfortunately, fate has decreed otherwise. At the start of April I was arrested. I was unable to write anything from prison. Only now, sitting here in the camp, bearing the burden of my sentence, am I able from time to time, after back-breaking work – to write to my friends – and thus create the illusion of communicating with a few people. This is one of many camp addictions and I too have rapidly succumbed to it. And please don’t be surprised that even now, in far from everyday circumstances, do I feel the desire to seek flight from many of the unnerving issues and people that surround me, by discussing about and reflecting on poetry. I don’t know if it won’t sound funny, I do it reticently and with uncertainty – I propose an exchange of opinions on various issues contained in your article about lyricism and lyrical values. If only you could send me a copy of this article! That would be a great joy for me. Ultimately, this is the only way to retain or protect all of those things which are assailed here every day in the camp and which must defend themselves with greater and greater desperation. Please help me in this difficult endeavor.

I send warm greetings and express to you my greatest respect,

Gustaw Herling Grudziński.

A copy of the letter was sent to my father by Janina Hera. The scholar came across it in the Ossoliński Library in Lviv in the “Ostapa Ortwina” resource, whilst gathering materials for her book ‘The fate of Polish artists in times of captivity 1939–1945 (Krakow: Arcana 2019). Dated December 23, 1966, in Journal written at night (vol. 3 1993–2000, Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie 2012, pp. 668–670), Gustaw Herling recalls the letter, commenting on its content “with great emotion”:

Although the letter is undated, I probably wrote it in the Yercev camp at the beginning of the winter of 1940, immediately upon my arrival in the Gulag, when for some time I became obsessed with establishing contact with the outside world, with reaching out to someone through the barbed wire […]. I wrote and sent two letters to Lviv, to Kleiner and Ortwin. Kleiner responded with a warm shake of the hand extended to him. Ortwin remained silent, although he was still alive at the time. He was shot by the Germans after they entered Lviv in the summer of 1941.*

The letter is an exceptional example of correspondence that a prisoner of the Soviet Gulag was able to write to “afford himself the illusion of contact” beyond the “other worldly” conditions of his imprisonment. It testifies to the extreme efforts “to cling to everything within oneself that is threatened daily in the camp, to defend it more and more desperately” through meditation, which was inextricably linked to poetry and literature. This imperceptible bond remained vivid in the mind, being expressed in a letter sent to Ortwin. It also transports us, in Gustaw Herling’s biography, to the years leading up to the outbreak of World War II, to the beginning of his Polish studies and the Nazi-Soviet joint invasion of Poland, to his experiences in the underground, to his brief stay in Lviv and Grodno prior to his arrest by the NKVD.

During his studies, in his late 1930s debut articles and essays he presented himself as a “sharp” literary critic. Moreover, as an editor, he cooperated with important magazines that dictated the course of cultural life in the interwar period. He also encountered leading figures among the intelligentsia, including Czesław Miłosz and Witold Gombrowicz. All of this occurred against a backdrop where “war hung in the air”, the premonition of the looming cataclysm that would hit Europe being at the forefront of the minds of young Warsaw University students.

Herling recalls this period during his speech at the conferral ceremony for his honorary doctorate at the University of Maria Curie-Skłodowska in Lublin on May 21, 1997, as follows:

When the war broke out, I was twenty years old, having studied Polish at the University of Warsaw for two years[…]. Everything appeared to point to my following in the footsteps of my master Ludwik Fryde, who was, alongside Kazimierz Wyka, the most interesting literary critic among the generation of thirty-year-olds, and that – perhaps – I would be tempted to pursue further Polish studies at the university, i.e. a so-called academic career. The war settled the issue for me, as it did for all those young people who mapped out their plans for the future. In my specific case, the NKVD determined the course of events, brutally putting an end to my first conspiratorial and military forays. For two years – the same length as the duration of my Polish studies in Warsaw – a writing table littered with books was substituted with prison bars in Grodno, Vitebsk and Leningrad and with barbed wire at a camp on the White Sea. (G. Herling Grudziński,To be and to write, in: Collected Works, edited by W. Bolecki, volume 3: Literary reviews, outlines, treatises 1957–1998, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie 2013, p. 565).

In late October 1939, Herling was assigned by the PLAN – Polish People’s Action for Independence (of which he was coincidentally a co-founder, it being one of the first military organizations of the anti-Nazi resistance movement) to traverse the eastern areas of the Second Polish Republic with the aim to pass through either Lithuania or Romania, in order to reach the West. He crossed the demarcation line and arrived in Białystok, where he witnessed the Sovietization of Polish lands under the occupation of the Soviet army. This information he shared during a conference in Burma in 1952, in the process of delivering the lecture entitled ‘My Personal Experiences in Poland and Russia 1939–1942’**, the manuscript of which is to be found in his archive. His retelling of the dramatic events of those years is intertwined with his journey from Polish citizen involved in the fight for independence, to prisoner in the Gulag. Herling outlines the Sovietization of Polish lands annexed by the Soviet Union as an “experiment” he bore witness to prior to his arrest and deportation. He ends this declaration with the following words: “between September 1939 and June 1941, the Russians arrested and deported to the remotest corners of their country about one and a half million*** Poles, Jews, Ukrainians and Belarusians who had resided in the eastern areas of the Republic of Poland before the outbreak of the war.”

This transitional moment from the country of his childhood and youth, the country where he studied Polish, where his career as a literary critic began, to the “other world” of the Gulag, served as inspiration for the creation of the extremely evocative story “The Hour of Shadows” (1963, in: Collected Works, edited by W. Bolecki, vol.. 10: Essays, Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2016, pp. 7–13). Within its pages, the twilight that descends suddenly from the mountains is the prelude to a pilgrimage leading him to the fringes of the empire into the bleak, black universe of the Gulag. It represents a farewell to “the last winter in my country”. The inhabitants of the eastern territories of the Polish Republic, incorporated into the Soviet Union, are oppressed and wear the look of fleeing shadows, however there is no way out for them. Here are a few excerpts, testaments to those days spent in Białystok:

In Białystok, life was concentrated around the main street, where the Soviet side of the Border zone established its postal headquarters and transit hub. In the stream of people flowing back and forth along it, they searched for relatives, friends, random postmen. From cards hurriedly, furtively spirited out from afar, information about loved ones was gleaned, written in a style whose brevity and expressiveness was unmatched by any pen put to use in the service of the imagination.

And next:

It was the beginning of December, the first snow was falling. In air still saturated with the humidity of autumn, the wet flakes melted rapidly, flowing in dirty streaks down the red banners hung across the street, hailing the arrival of the New Power; from towering portraits of the Ruler, from a plaster cast model of a monument to the invincible Army. The speakers boomed out the same words over and over…

From Białystok he ends up in Lviv and Grodno. The Soviet authorities are advancing, cutting off all possibility of escape for my father, who in Grodno falls victim to an informer who goes by the suggestive surname Mickiewicz. Arrested by the NKVD in March 1940, he was initially transferred to a prison in Grodno, then Vitebsk, and on to Leningrad, from where he was moved to a Gulag in Yercevo on the White Sea – the site of his “imprisonment and martyrdom”, which he detailed in A World Apart: A Memoir of the Gulag. In this famous book, the desire to bear witness in order that “the free world would know” flowed from the strong survival instinct of prisoner Herling. Ultimately it was a message that he was able to communicate, by enduring through that period, to a century dominated by totalitarian ideologies. Soviet prisons and the Gulag marked him out as a man and as a writer, they were the “prism” through which he observed the world he inhabited, and which he testified to in his works – as we read in his speech To be and to write, which he delivered at UMCS:

My experiences from 1940–1942 became a prism through which the writer views the current or potentially hidden reality. […] I wonder whether fleeting thoughts about my literary aspirations flashed through my mind while on those prison and camp bunks or during the so-called correctional work in the Soviet Gulag. It cannot be ruled out, since even in the hardest moments of murderous physical torment, I tried with all my might – If my memory serves me well – to maintain my observational senses in a state of constant tension, directing them both towards my immediate surroundings and deep within myself. This would serve as proof of my subconscious writer-like behavior, “gathering materials” for future retelling, if fate permits me to survive. Therefore a very rudimentary writing instinct flickered inside me, although it bore little resemblance to my pre-war interests. (To be and to write, op. cit., pp. 566–567)

The letter preserved in his archive serves as a testimony – seventy years on from the publication of A World Apart – to those “fleeting flashes of thoughts about […] writerly aspirations” and the effort “even in the most testing moments when one was exposed to mortal physical suffering” to “persistently maintain” a thread of that calling to literature, which corresponded to his belief in the power of representation, identity and testimony.

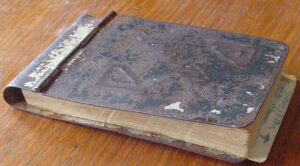

Gustaw Herling-Grudziński’s war journal. A scam from W. Bolecki’s archive, original in Gustaw Herling-Grudziński’s Archive in Naples

The future writer, released from the camp in March 1942 under the so-called amnesty for Polish prisoners which stemmed from the Sikorski-Maisky Treaty, wrote down his texts with brevity and succinctness in a notebook purchased en-route to the Polish Army being formed in the Soviet Union. In retrospect, the pages of faded annotations constitute the “seed” of A World Apart. The preserved notebook, despite his lengthy odyssey as a soldier and subsequent years spent in exile, remains in his archive. Gathered together and transcribed, the notebook was recently published in a critical edition of A World Apart: A Memoir of the Gulag edited by Włodzimierz Bolecki, which forms part of Collected Works, published by Wydawnictwo Literackie in 2020.

Wearing the ragged clothes of a former prisoner, my father traversed the Soviet Union to Kazakhstan. Then on to Iran, Iraq, Palestine and Egypt, in order to undergo military training in the Polish army formed by General Władysław Anders under British command. On March 9th, 1942, he joined up to the 10th Division in Kazakhstan. In the outline A dialogue about Commanders in 1970, along with Józef Czapski, he recalls waking up in a military tent he was assigned to, being accompanied by sentimental emotions while listening to a Polish choral song:

At the end of my tether, clothed in camp rags, starving, covered with ulcers. I was ordered to a tent where a few soldiers had gathered, already up on their feet, along with some prisoners and exiles, and the next day I was permitted to bed down on a straw mattress until wake-up call. […] Upon hearing the singing Polish choir, I expressed my thanks to God for being alone in that tent. Maybe all of those half-dead wanderers from the labor camps, as well as those exiles, shed a tear on that first day, after waking up to find themselves in the army? We constituted an army of prisoners, commanded by a prisoner and rebuilt with the reluctant consent of prison supervisors (G. Herling-Grudziński, J. Czapski, A dialogue about Commanders in: Collected Works, vol. 3, op. cit., p. 394).

Vitally important is the testimony he delivered during a speech on the occasion of being awarded the honorary doctorate at UMCS:

We were an army of prisoners and paupers, healing our physical and mental scars under the beating sun of Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Egypt, with a view to participating in the looming battles. The prevailing attitude at that time among soldiers set free from prisons and Gulags under the so-called Soviet amnesty, was silence. It ought to be viewed as a healing rumination on one’s own experiences. For myself, that silence signified that I was mentally working on a future book. (To be and to write, op. cit., pp. 565–566)

Pieced together, as if in a mosaic, are the fragments of epistolary and literary writing that Gustaw Herling managed to salvage from within himself during his stay in prison and the subsequent pilgrimage as a “soldier of freedom”: from the Gulag to military camps in the Middle East, onwards to the landing in Taranto, a stay in an English hospital in Noceri due to typhoid fever, through a short convalescence period in Sorrento, where he met Benedetto Croce and his family, to participation in the Battle of Monte Cassino, for which he was awarded the Order of Military virtue.

The choice of emigration firstly to Rome, immediately upon the cessation of the war, then on to London, where he relocated in 1947, bore fruit by means of journalistic and essayistic activity, as well as his writing debut, which came in the form of A world apart.

In his last essay and inaugural speech delivered on May 12, 2000 on the occasion of being bestowed with the title of honorary doctorate by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Herling returns to the path he opted for in his “dual literary life”:

Bypassing my first literary fruits in the years of my Polish studies in Warsaw, discounting the bits and pieces scattered throughout the press of the 2nd Corps, penned under tents of military camps in the desert of Iraq or on the front during the Italian campaign, my birth as a serious writer occurred in the Soviet labor camp, and came to fruition after the war. Shortly after the end of hostilities, there occurred for me two most important openings within the literary world. I was a co-founder of “Culture” in Rome along with Jerzy Giedroyc. Then in England I swiftly set to work on A World Apart which I had ruminated on at length – indeed, I had mentally noted it down – upon leaving Russia until demobilization. About a A World Apart I will say this: I was able to interfuse literature with an indictment of totalitarian violence. (My “double” life as a writer, in: Collected works, edited by W. Bolecki, volume 15: Varia, Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2021, p. 127)

The path of the exile, witness and writer is indelibly stamped across A World Apart, published in London in 1951, with a foreword by Bertrand Russel****. A World Apart attained its Polish publication in 1953, and from 1965 in the series of the Literary Institute, it became available to readers in Poland on account of Polish emigration and its publication in the so-called underground press.

Post-1989, after the collapse of communism, it saw the light of day again by way of official publications, attaining very high circulation figures and seeing numerous reprints. Additionally it was added to the list of compulsory school texts. The international circulation of the work has reached far and wide: from Europe, through the United States of America, Latin America, to Japan. A new interpretation is presented to us in the critical edition by Wydawnictwo Literackie, being enriched with texts, unpublished documents and photographs from the archive, highlighting the world in which my father created his World Apart, thus securing its place among the classics of world literature.

Dr. Marta Herling, historian, custodian of the Gustaw Herling-Grudziński archive at the Benedetto Croce Library Foundation in Naples. She participated in the preparation of a critical edition of her father’s collected works.

* Juliusz Kleiner (1886–1957) – historian and literary theorist. In the years 1920–1941 he tenured as head of the Department of the History of Polish Literature at the University of Lviv. Ostap Ortwin (1876–1941) – literary and theater critic. In the interwar period, one of the driving forces of cultural life in Lviv. At the outbreak of war, he was arrested by the Germans, and the circumstances of his death are unknown. At the turn of 1939–1940 Gustaw Herling met with both him and Juliusz Kleiner in Lviv. He enjoyed their support at the time of being admitted to the Polish Writers’ Union and obtaining a residence permit. He himself confirms this information in The Hour of Shadows, published in 1963 (The Hour of Shadows, in: Collected works, edited by W. Bolecki, vol. 10 Essays, Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie 2016, p. 10). J. Kleiner’s letter of January 25, 1941 is held in the Gustaw Herling Archive: AGHG 323. “Letters to G. Herling-Grudziński held captive in the camp at Jercewo” (see: Catalogue of the G. Herling-Grudziński Archive in the Foundation “Biblioteca Benedetto Croce”, ed. J. Borysiak, Warsaw: National Library 2019, p. 228).

** This was one of the “Lectures on Russia and Communism” that Herling delivered during a visit to Burma (May 13–June 4, 1952) at the invitation of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in Paris and the Bama Khit newspaper. See: Journey to Burma. Journal (1952–1953), in: Collected works, edited by W. Bolecki, vol. 15 Varia, Krakow: Wydawnictwo Literackie 2021, pp. 7–59.

*** In reality, during the four great deportations of 1940–1941, approximately 330,000 Polish citizens were exiled by the Soviets. (editor’s note).

**** A World Apart: A Memoir of the Gulag, English translation by A. Ciołkosz, London: Heinemann 1951; first Polish edition: Inny Świat. Zapiski sowieckie, London: Gryf Publications, 1953.

Translated by Jan Dobrodumow