Witold Chmielewski

Many children died of exhaustion, starved, or froze to death in the Siberian taiga, Kazakhstan steppes, and other regions of the inhospitable Soviet empire. Some of them lost their parents and loved ones. Those that managed to escape the “inhuman land” were left to wander all over the world. Over 700 of those children settled in New Zealand.

Around 18,000 children and youth were among the nearly 40,000 Polish civilians crossing the Caspian Sea to leave the Soviet Union with General Władysław Anders’s Polish Army. They had all found themselves in the “inhuman land” following four mass deportations from the Eastern Borderlands of the Second Polish Republic, conducted by the Soviets in the first years of World War II. Many children died of exhaustion, starved, or froze to death in the Siberian taiga, Kazakhstan steppes, and other regions of the inhospitable Soviet empire; some lost their parents and loved ones. Those who survived and were unable to leave were doomed to misery. Tens of thousands of children are thought to have remained in the Soviet Union.

From the “Inhuman Land” Into the World

The young Poles evacuated to Iran were looked after, provided medical assistance, and given the opportunity to attend Polish kindergartens, primary, vocational, and secondary schools. It was difficult for Iran to support such a large number of war refugees, however. With the British government’s support, Polish civilians, especially women and children, were relocated to the English dominions in Africa at that time: Uganda, Tanganyika, Northern and Southern Rhodesia, the Union of South Africa, as well as to India, Mexico, Palestine, and Lebanon. All those countries ensured they would have comfortable conditions for surviving the war period. In 1943, several hundred Polish refugees traveling on board an American ship bound for Mexico stopped in New Zealand for just over a day. New Zealanders gave them a warm and generous welcome. The Consul General of the Republic of Poland in Wellington, Kazimierz Antoni Wodzicki, along with his wife, Maria, were among those who visited the refugees. They both concluded that New Zealand had the capacity to accept Polish refugees, as well. Maria Wodzicka, in particular, strongly promoted the idea. Inspired by their advocacy, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Peter Fraser and his wife ultimately invited several hundred Polish citizens, primarily children, to come to their green islands. Those recruited for the trip were mainly from the Polish communities in Iran. On 30 October 1944, Polish refugees traveling on board the enormous American transport ship USS General GM Randall, carrying several thousand soldiers, reached Wellington. The welcoming ceremony the New Zealand authorities and citizens organised in the port for the Poles was touching. The next day, the refugees were transported by two trains to their permanent residence – a camp in Pahiatua. Large numbers of New Zealanders (members of social organisations, students waving white and red Polish flags) greeted the travellers at the railway stations. Children were given sweets and toys, and parcels with clothes. The sight of the refugees arriving from afar aroused sympathy. The Polish children’s arrival was widely reported in the national press. One might say that almost all New Zealand showed solidarity with the newcomers.

Little Poland in the Land of Kiwis

On 1 November 1944, 733 children, accompanied by 105 adults, moved into the camp in Pahiatua, known from then on as “Little Poland”. They were teachers, caretakers, doctors, nurses, cooks, service workers, etc., in total – 838 people, mostly women and girls. As a result of family reunification efforts, by March 1949, 13 more children and 173 adults subsequently arrived in New Zealand – mainly soldiers from General Anders’s Polish II Corps. Between 1 November 1944 and March 1949, there were 1,031 persons associated with the Pahiatua camp under the direct care and concern of the New Zealand authorities. Three of them died within this timeframe. The 184 girls and 119 boys who had arrived in Pahiatua were officially declared orphans. Nearly 270 children were fully orphaned (the deaths of both their parents had been confirmed), more than 180 had only fathers, and 106 – only mothers. Most of the half-orphans lived outside the camp. There were very few children in Pahiatua whose parents were both still alive. Many children, however, had relatives in the Soviet Union and other countries far from New Zealand, including Poland. There was no reliable information concerning many of the parents. Some children were not even sure what their real names were, and some only learned their own surnames from letters from their parents, extended family, friends, or former neighbours.

Orphanhood and family separation caused distress, frustration, and unpredictable behaviours and attitudes among the children. Therefore, educating them was difficult and required a lot of empathy, kindness, and understanding from their teachers, tutors, and all other camp employees, both Poles and New Zealanders. On the initiative of Consul Wodzicki, the Supreme Court of New Zealand established a Guardianship Committee (Welfare Committee) to regulate the standard of care for the orphans.

The Most Important Street – Warszawska

The camp was located near the town of Pahiatua, in the green meadows where herds of cows and sheep grazed. The refugees lived in 14 wooden one-story buildings. Each of them accommodated 42 to 60 people. Families of three to six people lived in 20 small houses with a kitchen and three rooms each. The camp had electric lighting. The larger, general buildings had central heating, while the individual houses were coal-fired. There was a recreational hall, which served as a chapel on Sundays, a scout club, a swimming pool, a gymnasium, and a library which consistently grew its collection with books donated from Europe and the United States. The streets in the development were named after Polish cities and notable Polish people. The most important one was Warszawska Street, named after the Polish capital, Warsaw.

The New Zealand male and female staff, mostly soldiers, put a lot of effort into making the camp comfortable and accommodating for the refugees. Over 100 volunteers, mostly members of the Polish Children’s Hospitality Committee, prepared their rooms and made over 800 beds for them. They even left bouquets of flowers on the nightstands. Major Peter Foxley became the New Zealand commandant of the camp, and later – until the end of its existence in 1949 – Major E.J.C. Finny was in charge. On the Polish side, Jan Śledziński, a delegate of the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare and the Ministry of Religious Denominations and Public Enlightenment of the Polish government in London, was its manager until 1945. After him, the Interim Committee for the Polish Children in Pahiatua took over management of the camp, and then, from April 1946, Szczęsny Zaleski, a representative of the British Interim Treasury Committee for Polish Affairs. After Zaleski died in 1948, Prime Minister Fraser appointed his widow, Ellinor Zaleski, to look after the Poles benefiting from government assistance. When the British and New Zealand authorities withdrew their recognition of the Polish government in exile, the government in Wellington assumed financial responsibility for the camp. Clothing for the children and teenagers was not an issue. Their clothes mainly came from New Zealanders’ donations and army resources. Their distribution was handled by an organisation founded by Janet Fraser, the New Zealand Prime Minister’s wife, thanks in large part to Maria Wodzicka, who was representing the Polish Red Cross. Wodzicka looked after giving clothes to those in need, among other things. Because of her efforts, the camp also received a piano and six radios.

In New Zealand

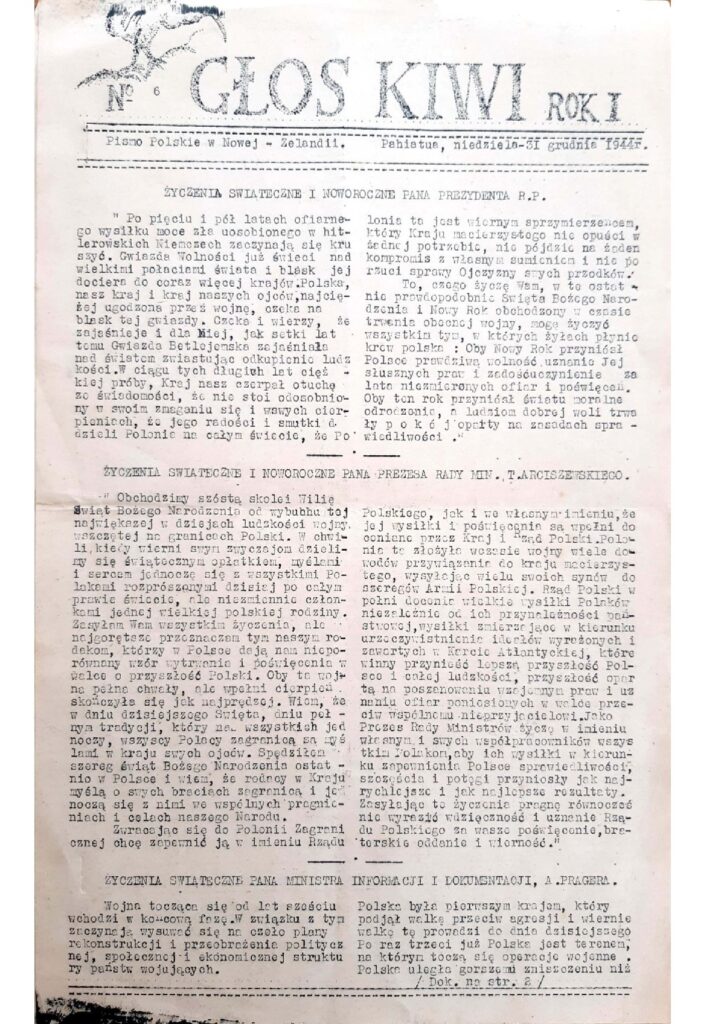

Relations between the camp residents and New Zealand society developed very positively. The New Zealand press (Auckland Star, The Weekly News, Women’s Weekly, Marist Messenger, Observer) published pieces concerning camp matters as well as those of wider Poland. In the camp itself, the magazine Głos Kiwi (Kiwi Voice), also devoted to camp affairs and the situation in Poland, was published in Polish. In early 1945, the children from Pahiatua staged a nativity play (Jasełka) for people in the town and neighbouring farms. The Polish youth choir led by Maria Jadwiga Żerebecka put on numerous performances for the New Zealanders. The camp management reached out to families with Polish heritage who had been living in New Zealand for several generations. Most of them no longer knew the language of their ancestors but were very proud of their Polish roots. In May 1945, residents of Inglewood – mainly Poles – invited 74 children to their homes for the holidays. Another 200 children also went to spend their holidays with New Zealand families. Similar initiatives were organised in the following years. The children remembered this for years to come.

The Pahiatua camp frequently received guests, including, on more than one occasion, Prime Minister Fraser and other dignitaries of state. In January 1945, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Wellington, Metropolitan of New Zealand, Thomas O’Shea, came for a pastoral visit. The visit of Archbishop [Giovanni] Panico, the Apostolic Delegate to Australia and New Zealand, was an important event for the Polish community. In January 1947, he visited the Wellington boarding house of Pahiatua students run by Monika Alexandrowicz, an Ursuline sister.

Preserving Polish Identity

A kindergarten, two elementary schools (one for girls, the other for boys), and a general secondary school were established in Pahiatua. Tailoring courses were also organised for the older girls. The basis for the school system were the provisions of the Polish Act of 11 March 1932 on the Education System. Pre-war curricula were enforced in all schools, with the addition of English. Experienced staff (e.g., school inspector Józef Holana, headmistress of the secondary school Halina Ziąk, headmistress of the elementary school Krystyna Skwarko, Jadwiga Tietze) taught the classes. The children and teenagers were already being educated on board the ship on their way over to New Zealand. Many of the teachers had worked in Polish schools and educational institutions back in the Soviet Union, as well as in the Junak schools organised by the Polish Army in the USSR, or in the educational institutions in Isfahan and other Iranian cities.

Because many children had little memory of their homeland, and the older ones had been subjected to various forms of communist indoctrination in the Soviet Union, teachers made an effort to prevent their denationalisation and to educate everyone in the spirit of deep patriotism. Reverend Michał Wilniewczyc, who had arrived along with the refugees, and who also taught religion in secondary school, was especially committed to this cause. In the homilies he delivered during Mass, and in discussions with adults in the camp, he expressed his view that Polish children should be shielded from the influence of New Zealand society and prepared to return to their free homeland. Most of the teachers, as well as the government delegate, Jan Śledziński, shared this view. However, because of the post-war changes to Poland’s borders, its new political situation, and the rise of Soviet influence on the country, the vast majority of teachers, other adults, and students from the eastern territories of the Republic of Poland had nowhere to return to. This being the case, the educational goals changed. Their new premise was to prepare young people for self-sufficient life in New Zealand until the conditions for returning to an independent Poland were met. This was the official position taken by the Polish government in London. For this reason, youths were provided job-specific training through craft workshops and courses, and the oldest boys and girls went to work in various companies, industrial plants, or farms. After the Polish secondary school was dissolved, a significant number of young people continued their education in private Catholic secondary schools, scattered all over New Zealand. This education was largely at the expense of the Church. The clergy, traditionally associated with the Irish Church, appreciated the deep religiousness of the Polish children and youth.

They Stayed on the Green Islands

The number of Polish children in Pahiatua naturally decreased each year. Beginning in May 1946, camp residents gradually began to move into boarding houses outside the estate. The first, for boys only, was in the Island Bay district of Wellington. A year later, the girls-only boarding house “Ngaroma” was opened there as well. These boarding houses were usually run by Ursulines. In March 1949, the Pahiatua camp was shut down. The youngest 42 boys who were left moved into a boarding house in Hawera in May that same year. The boarding house residents attended New Zealand schools, and some older boys and girls went to work. Preserving their Polish identity became a challenge again. The entire Polish community in New Zealand, supported by the leading figures of the Polish community in London (Edward Raczyński, Władysław Folkierski), made a great effort to reach young people by various means to teach them the Polish language, history, and culture. Polish boarding houses, especially girls’ ones, became vibrant centres of Polishness. Professor Kazimierz Wodzicki and Reverend Leon Broel-Plater, who was a new priest for Poles in New Zealand and the former chaplain of President Władysław Raczkiewicz, were particularly renowned for promulgating the national character of education. During his ten-year stay in New Zealand, the Reverend visited all the Polish communities, even the small ones, especially those connected with Pahiatua.

Another very important issue for all Polish children rescued from the “inhuman land” concerned the propaganda-based demands repeated by the government in Warsaw that the children be returned to their homeland. These demands, however, were met with staunch resistance. By 12 May 1950, only 49 children who were brought up in the camp and a dozen or so accompanying adults had gone back to Poland permanently. 17 children went to various Western countries. The other camp children started families and settled in New Zealand. The girls went on to work in offices, hospitals, factories, clothing mills, and in sales. The boys preferred well-paid work in factories, the automotive industry, communications, and crafts. A dozen or so took up farming. Some completed their higher education and even earned academic degrees. Several ended up working in New Zealand’s central offices or diplomacy. After Poland gained full sovereignty, they visited their former homeland, which they had always carried in their hearts, many times. They passed on their love for Poland to their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Folklore, traditions, and Christmas and Easter dinners are an intrinsic part of the Polish holiday celebrations in New Zealand. Until recently, the Pahiatua children’s community was the backbone of the Polish community in New Zealand. As of today, less than 200 Pahiatua children still live on the green islands.

All illustrations and photographs above come from Author’s collection.

Witold Chmielewski is a professor at Academia Ignatianum in Cracow

Article translated from Polish by Monika Lutostanski