Tomasz Kizny

The shadow of a chopper flickers across the green forest-tundra, cut through with rivers. As far as you can see there is no human settling. Suddenly, a regular line appears like a lash, cutting across the landscape and ending in a blue haze on the horizon. The pilot of the chopper turns around and shouts through the noise of the engines: Vot ona – stalinka. [Here it is – stalinka.]

Dead Road, stalinka, transpolarka – these are the customary names of the unfinished Chum railroad, which ran between Chum (now called Seida), Salekhard, and Igarka, bulit from 1947 to 1953 by around 70 thousand prisoners, including Poles. A route of 1,300 kilometres on the edge of the Arctic Circle was to be the first part of the Transpolar Mainline, running from the coasts of the Sea of Okhotsk and to Chukotka. Stalin intended it to be a duplicate of the Northern Sea Route, with the same military and economic importance. However, given the scale, field conditions, and gigantic costs, the project was irrational. Construction was very difficult: during the summer, the melting ice cap flooded the railway embankment, the tracks deformed, and the bridges collapsed. The 700 kilometres of the route that were finished by 1953 required continuous repairs. The absurdity of transpolarka continued until Stalin’s death. Two weeks after his funeral, the USSR authorities ordered an immediate shutdown of the construction. Trains, building materials, and around 100 forced-labour camps were abandoned in forest-tundra.

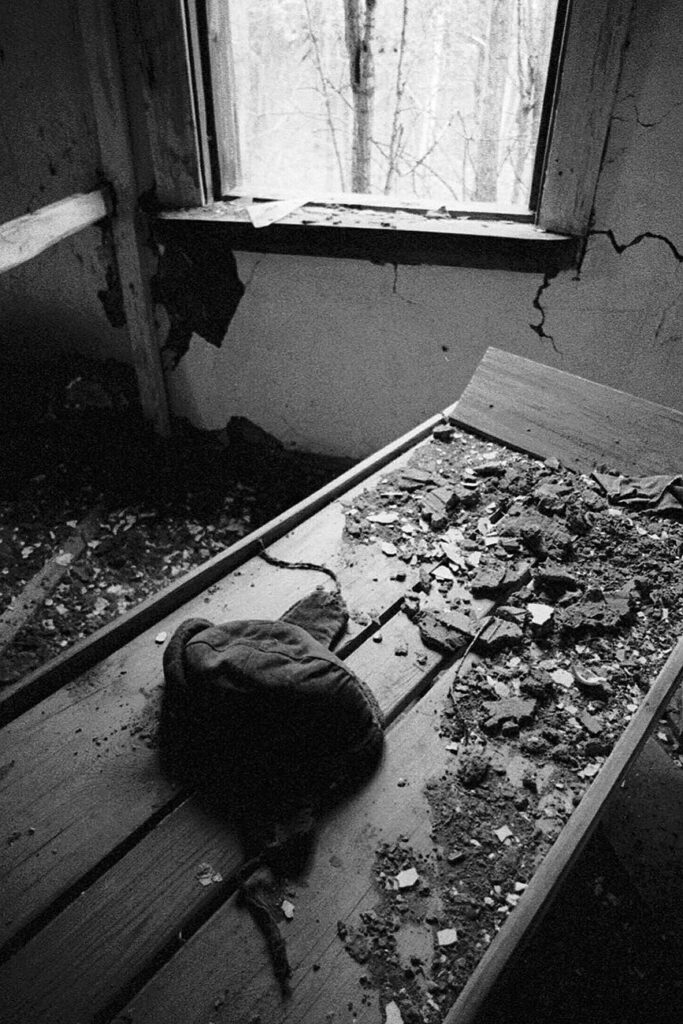

The chopper dropped off our expedition of three people on the transpolarka in the summer of 1990. We are fought our way through the overgrown route of Dead Road. Once in a while, the railway embankment disappeared into the mud; we crossed collapsed bridges; like surreal ghosts, we saw rusted railway engines standing on the tracks in a green thicket. Every 8 or 10 kilometres, we found the remains of the forced-labour camps for groups of about 500 prisoners: the dark interiors of the barracks, bunk beds along the walls, a freestanding stove in the middle, abandoned prisoners’ gloves, felt valenki shoes, warm caps. Silence, just the sound of tweeting birds outside. There is no feeling of terror – just the awareness that the human tragedies described by Solzhenitsyn, Herling-Grudziński and Shalamov took place.

Nature is consuming the camps, as if trying to wipe away the traces of human madness. Wild greenery is pushing into the cracks of the barracks – birches and cedars are overgrowing the watchtowers. Fallen posts with rusted barbed wire are rotting in the grass. The camp cemeteries are basically impossible to find in the thicket of greenery.

The Dead Road is often presented as an allegory of Soviet communism: a road that leads to nowhere, built despite common sense, paid for with the lives of millions of victims .

After two weeks we got to Jermakov, an abandoned neighbourhood on the bank of the river Yenisei, also built by prisoners – the main base of the eastern part of the stroyka [building site]. Its only citizen is a fisherman, Borys Chochuyev. He lives there alone as an involuntary “curator” of this museum of terror and the absurd, which starts at the door of his house and continues hundreds of kilometres of Siberian wilderness. On a set day, a helicopter will take us to Igarka, and we will go back there in spring 1991.

Tomasz Kizny is a photographer and journalist, author (with Dominique Roynette) of a photo album entitled: Gulag, Warszawa 2015.