Małgorzata Król

One may ask how it even became possible for a mother of six orphaned by their father children to join Szymon Konarski’s conspiracy? It is hard to believe that, burdened with the responsibility of a large family, she could (wanted to?) devote herself to conspiratorial activities, knowing the consequences, risking the happiness and safety of her own and her loved ones. She became involved with the association probably not anticipating that she would soon become known as Konarski’s main collaborator, who would also be a special prisoner after her arrest.

In prison and on the Siberian trail

Why did she become so useful? Probably because of the independence of action. Devoid of her husband’s support and confronted with the need to take on male responsibilities (such as administering estates), she was, in part, prepared for the difficult conspiratorial work. Considered a woman gifted with an extraordinary sense of intelligence and great strength of character, Felińska was swiftly introduced to the organisation’s work. She organised and ran an ‘office’ and helped facilitate exchanges of correspondence with the émigrés. Following the directive of the General Assembly of the Association of the Polish People that women should form separate circles, she received permission from Konarski to establish them in Volhynia and Podolia. The female members were to copy proclamations and programme papers, act as liaison workers and teachers.

The move to the city of Kremenets helped with the more intensive activities. On her arrival, she rented a storied tenement house where Konarski could visit her without any problems. One of the meetings (May 1838) resulted in a demand for an intensified propaganda campaign, which was linked to the need for a printing press. The Koszary farmstead, located near Lisów, was chosen as the site for its operations. Felińska’s sons (Alojzy and Zygmunt) were to become the typesetters’ assistants.

The trouble, a result of his involvement in clandestine structures, began in July 1838 with a seemingly insignificant incident. One night, a casket containing money and documents was stolen from Felinska’s house. The loss was agonising, as it deprived the family of the means to support themselves for a few months, and the lack of documents brought complications to business. Having called the police, Felińska wrote to the renters asking them to send financial support. A few days later, the house was surrounded by the local gendarmes, who appeared in the courtyard. Although Felińska was assured that the purpose of the unusual visit was to investigate the theft that had taken place, she did not believe it. A search was carried out and the occupants of the house were left under guard. Eleven days passed [Pam. Z. P., 38] pending orders from Zhytomir. Finally, the courier who arrived announced that Felińska was to be taken immediately to Vilnius, where the Commission of Inquiry would decide on her case further. She set off, leaving her paralysed grandmother and six children in Kremenets. ‘I would hesitate in vain to describe the tearful scene that took place at the parting good-bye. The despair of the children, who burst into tears and clung to the arms, legs and clothes of their mother, who was violently dragged away and was half-dead with pain, was so overwhelming that the executors of the cruel verdict themselves could not keep from being moved’. [Z. S. Feliński, Paulina. Córka Ewy Felińskiej (Paulina. Ewa Felińska’s Daughter), Lviv 1885, p. 100; further in the text – P, 100].

Instead, the children were led to believe that their mother’s imprisonment was the result of a misunderstanding and that she would soon return. But as the weeks passed without bringing the expected return, hope waned. In this situation, the eldest daughter, Paulina, whose only support was her mother’s letters, started to look after the family.

Various accounts of Felińska’s attitude during the interrogations, often mutually exclusive, have survived. Until recently, the most common line was that she revealed most of the members of the conspiracy in the very first days. Felińska was considered to have discredited her acquaintances through recklessness, and although she withdrew from some of her testimony, every lead that was pointed out was checked anyway, and she harmed many. Can this ‘dark side of Felińska’s biography’ be explained? It now appears that, thanks to the findings of, among others, Wiktoria Śliwowska, the allegation of Felińska’s naivety during the investigation is untenable.

In 1987, Stanisław Makowski, on the grounds of excerpts from the police–court files of the trial in Kyiv, found in the Kyiv State Central Historical Archive, attempted to argue that Felińska, who was actively involved in the union, ‘[…] was a very bad diplomat and through sheer recklessness betrayed’, and that it was to Felińska that Salomea Bécu also ‘owed’ her arrest. At present, a more plausible view is that Bécu was compromised by Paulina Wilczopolska’s testimony of 29 September [/10 October] 1838, in which she stated that she had heard from Mrs Felińska that she belonged to a women’s association, resulting in a summons to appear before the Kyiv Commission of Inquiry for as many as seven of them (including Bécu).

As doubts proliferated, the Vilnius commission was forced to refer the matter to the Kyiv commission. In Kyiv, Felińska was imprisoned in a citadel, where she was placed in conditions unequally harsher than those she had experienced in Vilnius. There, during her interrogations, she learnt that the committee was in possession of information according to which a large group of women belonged to a secret organisation. She, however, maintained that such a union had not been formed and that the ladies named by the committee neither belonged to it, nor even heard of it.

Wiktoria Śliwowska, who had access to documents preserved in Kyiv’s archives, said that Felińska did not allow herself to be lulled by interrogators and did not answer questions as foolishly as rumours suggested, and that the investigative commissions probably wanted to discredit the woman.

On 13/25 February 1839, the trial was concluded. Felińska awaited her sentence in Kyiv prison almost peacefully. However, she was downright shocked when it was announced. Admittedly, rumours were already circulating at the beginning of March that the women would be sentenced to indefinite exile, but she refused to believe them.

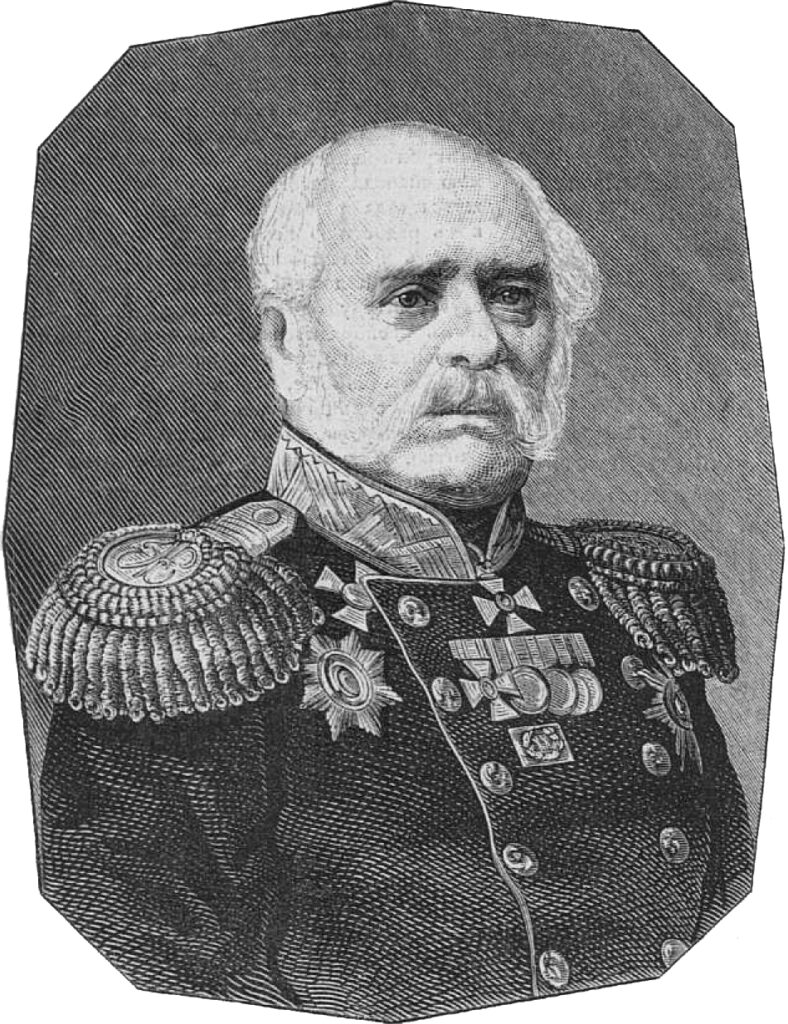

Dimitrii Bibikov [Kyiv governor-general – editor’s note] considered Felińska to be one of the most active participants in the conspiracy and called for her to be sent into exile with deprivation of state rights and confiscation of her property. The sentence was commuted by Tsar Nicholas I. Eventually, she was to be administratively exiled ‘for eternal residence’, without loss of state rights, to Berezovo [on the Ob River – editor’s note].

In mid-March, the children received a shocking letter from their mother: ‘[…] I am on board; I want to spend my last moments with you, my dear children. I cannot describe to you my grief at being separated from you, for this cannot be expressed in words. I will not write you words of comfort – may God send it to you. […] I am well, I’ve got everything I need, everything has been provided for me in a motherly way: money, things, food. For God! Please cherish your health, that’s one thing I ask of you; God will give the rest. I still don’t know where I am going, the order will be served on boarding. Keep well, stay calm, trust God… They’re rushing me’ [P., 129–130].

The need to find foster carers for the children was a matter of urgency, for according to the order of the governor-general Bibikov, the orphans were to be placed in government care, which resulted in their deportation to the depths of Russia and placement in government institutions [Pam. Z. P., 52]. So Pauline took the two youngest ones away first: Wiktusia to foster carers chosen by her mother, and Julka to a secondary school in Zhytomyr. As an elder, Szczęsny went to Kyiv ‘[…] to present himself to the governor-general, who welcomed him gladly, but urged him into military service by promising promotion and patronage. Szczęsny, however, did not deviate from his intention to complete the studies he had begun, presenting that he was still too young and that after completing his studies he could be more useful in any profession, and having mathematical abilities he would be happy to be an engineer’ [Pam. Z. P., 57].

Zosia stayed at Antonina Zubkowa’s family home, while Alojzy reported for duty at the office of the Zhytomyr governor [of the main court – editor’s note], which was supposed to enable him to be reunited with his mother, because ‘[…] whoever had served at least a year in the country received a double salary and a promotion, if they voluntarily moved to Siberia […]’ [Pam. Z. P., 57].

The orphaned children remained in the country and the mother had to face the nightmare of travelling to Siberia.

Felińska’s Siberia

When she arrived in Berezovo many months later, she realised that the place she had been sent to was ruled by extremes. The differences in civilisation and culture were shocking and infuriating. She did, however, speak with appreciation of an uncouth but less perverse northern civilisation. For if anger manifested itself more violently, revenge was often not necessary, and forgiveness was valued more highly than the defence of dignity. There was no exaltation, but a simple acceptance of the rights and duties imposed by the social hierarchy. The lower classes not only respected their position, but ensured that the barrier separating them from others was not crossed. She also had to admit that theft, common in Europe, was an extremely rare occurrence here. When it happened, it was clear that none of the locals had committed the wrongdoing, and it was the result of the activities of common criminals, of which there was no shortage among the exiles. Theft was thus the fruit of a ‘higher civilisation’.

However, the comparison was not always in favour of the nationals. There would have been behaviour that not only defied common sense, but put people’s health and lives at risk. She was stunned by the treatments the expectant mothers were subjected to. For although ‘the government sent […] midwives and doctors here, the people are so accustomed to certain superstitious practices that […] the doctor or midwife, though called, had to tolerate, or their advice was not listened to. Before going into labour, the distressed woman has to be watered with soap, gunpowder and various spices, in addition to enduring the jostling of her body in various directions, bending to the most uncomfortable positions, to the last strength of exhaustion’ [Wspom. I, 181–182].

Felińska endured her exile bravely. She found strength in knowing that she had to get through this time and get back to her children. The lack of touch with her family meant that the hope keeping her alive was waning. While waiting for news from home, she vowed that her children’s health would be the last prayer she would trouble God with. But when the first, long-awaited letter arrived, joy was mixed with trepidation, and the vow… was not honoured. Surprised by Paulina’s request for permission to come to Berezovo, she prayed again – now for prudence. Considering her daughter’s request became a battle between reason and heart. Finally, she felt that by not being able to help her children, she would not restrain their free action. She let Paulina make the decision herself, convinced that she would more easily come to terms with the obstacles standing in the way of her intention when they were independent of her mother’s opinion and will [Wspom. I, 145]. She praised Szczęsny’s decision to join the Corps of Engineers and put Julian in grammar school. She advised Alojzy against military service in Tobolsk [P., 146–147]. She wrote several separate letters to Paulina, trying (finally successfully) to influence her to change her decision to reject Adam Szemesz’s proposal.

She almost completely avoided descriptions of her Siberian everyday life, unless the recipient expected them. Enriched with a wealth of details of her life in Berezovo were letters to her youngest daughters, Wiktoria and Zofia. At times in them, one could read descriptions of Christmas celebrations, or the most trivial everyday events, the changing aura, and the Ostyak customs.

In Berezovo, she had moments of happiness too. The news of Paulina’s marriage to Adam Szemesz made her happy. She was upset that an event so significant in her daughter’s life had taken place without her attendance. Although she tried to hide her pain with the joy of the relationship concluding as she expected, she failed to do so. Emotions subtly creep into a letter to Antonina Zubkowa regarding Paulina’s upcoming trip: I am sending two pieces of fur lining (very popular here): one for Paulinka, and the other one for Zosia. ‘[…] For my Paulinka, I am also sending a picture with a blessing and a box showing a landscape I have made with my hair, as she so wanted to have something made by me. On top of that, I have sewn a cape made of baby reindeer fur. Oh my God! If someone had told me a few years ago that when Paulina would be getting married, I would make such a dowry for her, I would have never believed them’. [P., 235–236].

She made no secret of her delight at the love between her co-exile Józefa Rzążewska and dr Ignacy Wakuliński completed by a holy marriage entered into on 15/27 March 1841. [Wspom. I, 344]. However, the greatest joy of all was the news that she was allowed to leave Berezovo! This is what she wrote to her children: ‘Get down on your knees and thank God for his great mercy on us. At this moment, I received a document allowing me to leave Berezovo and go to Saratov. In three days’ time, God willing, I will be on my way and I will be constantly getting closer and closer to you, until I finally stop a few hundred miles away from you, in a warm and plentiful country. My head is so messed up that I am unable to write anything more” [P., 249].

Although a gruelling journey awaited her again, she was not terrified. For she knew that she would be getting closer to her loved ones. Leaving Berezovo was accompanied by joy and gratitude on the one hand, but fear on the other. Here she never felt like a stranger. The people she met, so simple, open and friendly, welcomed her warmly and included her in their community. She was apprehensive about whether she would find anything like them in Saratov.

And it was in Saratov that she first became fearful of the future. In Berezovo, she received an allowance from the government, which did not provide a decent life, but secured the essentials for a living. When she arrived in Saratov, she found out that the governor there had not received any instructions regarding the money owed to her. It was necessary to reclaim the support provided so far. Her request was granted and, despite her concerns, the reception by the locals was also very kind.

However, her life in Saratov was completely different to what she had wished for. On arriving here, she had intended to lead a secluded and quiet life, and almost immediately had to start an active social life. She found it irritating to have to attend meetings, which only her ill health relieved her from attending. So, not quite accepting the local customs, she was meticulous about ensuring that she had at least a modicum of privacy. Here she also noticed that there was something superstitious about her, that she was afraid of good fortune, a series of good moments, because these (she believed) could herald a solstice, the arrival of something that would severely hurt. She saw that she could cope in difficult situations, that she could then be brave and strong. But not at times of happiness. This was the case when the children visited. The joy of Szczęsny’s arrival was overshadowed by some invisible feeling of fear of the necessary departure. [Wspom. II, 229]. Waiting for the Szemeszs’ arrival was more a time of anxiety than of joy. She feared for her daughter’s health and was unable to control her anxiety [Wspom. II, 238].

A growing family and increasing financial needs forced her to take up gainful employment.

Felińska – the writer

As per her children’s wish, she took up writing. For this decision was accompanied by misgivings, she decided to prepare an article on the acceptance of which her literary future depended. She chose Tygodnik Petersburski (The St Petersburg Weekly) as the platform for her debut, whose editors and contributors at the time (Józef Przecławski, Michał Grabowski, Henryk Rzewuski, Ignacy Hołowiński and Ludwik Sztyrmer) she trusted. She didn’t have the courage to sign the text with her own name. She used a nickname and, as Wenerada Kokosz, adding a humorous ‘Letter to the Publisher’, sent her article on the issue of the progress of mankind [Wspom. II, 271–288]. She was afraid, because she believed that only young people, who bear an abundance of strength as yet undeveloped, could afford such extravagances. An old age [she was 50 years old at the time!] learnt ‘[…] the exact limit of its strength’ [Wspom. II, 289]. Her debut piece, entitled ‘Myśli o postępie ludzkości’ (‘Thoughts on the progress of mankind’), published in Tygodnik Petersburski in 1843, favourably received by Ludwik Sztyrmer, the author of a kind review, managed to convince her to commit her time to writing.

Work on her first novel Siostrzenica i ciotka (The Niece and the Aunt) was interrupted by a family tragedy. Six months after her arrival, her beloved Paulina died during childbirth, leaving a baby boy, who was named Paulin in his mother’s honour. It was a time of the greatest test in exile. So far, the hardships were made bearable by her deep faith in the fact that God, by afflicting her, was protecting her children. She trusted and prayed. But her prayer was not answered. Not only did she have to experience, but she also had to be present at the death of her dearest daughter.

It took her a long time to find peace again. There was no quick return to the writing that had been practised either. She tried and… regained her peace of mind: ‘[…] For I got up from the desk far happier and calmer than I had sat down. I have gained better health and good thoughts’ [Wspom. III, 59].

When the much-anticipated release came, she realised how many obstacles she had to overcome before reaching the country. She could not come to terms with the thought of leaving Paulina’s mortal remains forever. Paulinek was only six months old and needed a wet nurse. Taking the woman who had fulfilled this role so far from Saratov was impossible [Wspom. III, 136]. Finally, they wanted to return together. For this, they still needed the release of her son-in-law Adam Szemesz [he was exiled to Kherson in 1842 – editor’s note].

She also did not know where to go. But having accepted that the older children had found ‘[…] foster carers and guardians of such a kind that I would not be able to replace them; while I myself can still work and without the help of the estate be no burden to anyone […] [Wspom. III, 145], she decided to go to Lithuania, where she had loved ones and this place never ceased to be the ‘homeland of the soul’ [Wspom. III, 146]. The heart wanted to come here, reason suggested other solutions, and the children were also drawn to Volhynia.

The trip was delayed. Szemesz was not released. Finally, Ewa Felińska, leaving her son-in-law in exile, left Saratov on 17/29 May 1844 with Paulinek and Zosia.

Back in the country

On her return, she busied herself not only with her ruined estate, but also with her writing. Siostrzenica i ciotka, which had been prepared while still in Saratov, was submitted for the assessment of Michał Grabowski. His rather positive review motivated the author to prepare more: Pan deputat, Hersylia, Wigilia Nowego Roku and Pomyłka (Mr Benefit, Hersylia, New Year’s Eve and Mistake).

The first scripts failed to find a publisher soon enough and were published not without problems. The story of the publishing woes of Ewa Felińska’s books is told in the preserved correspondence between the author, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski and Adam Zawadzki. The letters reveal the reasons why Felińska’s novels had to wait five years for publication, even though they had already been published in 1844. Siostrzenica i ciotka and Pan deputat were prepared for publication. It is difficult to say from whom Felińska learnt the truth about the poor value of her novel prototypes. Nevertheless, perhaps prompted by the publishers’ criticisms, perhaps by her own but more careful reading, she found it necessary to rewrite them.

The case is quite different when considering her memoir works. After returning from exile, having settled in Voiutyn, Felińska made the acquaintance of her neighbour and later friend and master Józef Ignacy Kraszewski. As early as 1845, she sent him some fragments of her Siberian Memoirs. When the writer’s letter arrived, reporting on the extremely positive impression the sent text had made on him, she could not hide her satisfaction. The print edition confirmed Kraszewski’s premonitions. Financial negotiations around a separate edition of the Memoirs had been underway since January 1850. The edition circulated rapidly and, as expected, was received enthusiastically. So there was nothing left to do but to meet readers’ expectations and think about a reissue.

At the same time, she began work on Pamiętniki z życia (Diaries of a Lifetime), which was also soon to be published. She did not abandon work on her novels either. But these did not bring publicity or satisfactory income. They did not enjoy readerly acclaim and fared poorly both in confrontation with the circulating readership achievements of their predecessors (e.g. Maria Wirtemberska, Elżbieta Jaraczewska) and even worse in juxtaposition with the burgeoning romantic moral novelism.

The question can be posed: why, having suffered so much adversity, criticising her talent, did she not give up and continued writing and publishing her works? The answer is prosaic – out of poverty. After her happy return from exile, she found a shelter in Voiutyn, but ‘[…] the estate where my husband and I lived most of the time came out of administration destroyed, burnt down, encumbered […]. In the midst of utter ruins, I barely found a place to shelter my head from the rain, and here […] I endured the hardest misery of my life for a year and a half’ [a letter to Julia Starorypińska, née Raciborowska].

Who knows whether poverty did not also become one of the causes of Felińska’s premature death? After her return to Voiutyn, it was precisely because of poverty that she severely declined in health: ‘I struggled with my illness for a fortnight. Loss of appetite, sadness, the unspeakable tightness brought me down so much that life became a burden. She eventually developed severe biliary fever with an attack to the brain’ [P., 287].

After that, she never fully recovered. She slimmed down and her strength waned. In one of her last letters to her children, she wrote most frankly about her poverty and her premonition of her imminent death: ‘And here is poverty! I have already sold two cows to meet our more urgent needs. I only have every faith in God that as long as he keeps me in this world, he will also remember my needs; and perhaps the moment is not far off when all needs will cease’ [P., 314–315].

Just before her death, she finished the second series of her Memoirs. When she typeset it, she confessed: ‘[…] It was with great shyness that I released the continuation of my Memoirs to the world and sent them back to Mr Zawadzki. I would far prefer them to lie in a file, left to their future fate, but much he does that must, and where must, there the will of man must yield with humility. […] An old age must give birth to infirm children alone, so they had better not be born’.

The first reason she wrote was life’s necessity. The second one was her commitment to Konarski’s ideas, who in his programme assigned women the role of maintaining nationality, obliging them to make beneficial use of their talents, including literary talents. By the end of her life, Felińska had ambitious plans in this area too, of which she wrote to Zawadzki: ‘[…] I am thinking of starting to work on the subject of raising Polish virgins. I would therefore ask you, if it is possible, to send me the catalogue of educational writings found in the bookshop, so that I know exactly what our writing is rich in and what it lacks’.

So she had both plans and dreams, which death no longer made it possible to fulfil. On 20 December 1859 / 1 January 1860, she died in Voiutyn surrounded by her children.

Dr hab. Małgorzata Król lectures at the Catholic University of Lublin

The article is based on the book: M. Cwenk [M. Król], Felińska, Lublin 2012.

Mid-titles by the editorial team.

Translated by Małgorzata Giełzakowska