Wiesław Caban, Lidia Michalska-Bracha

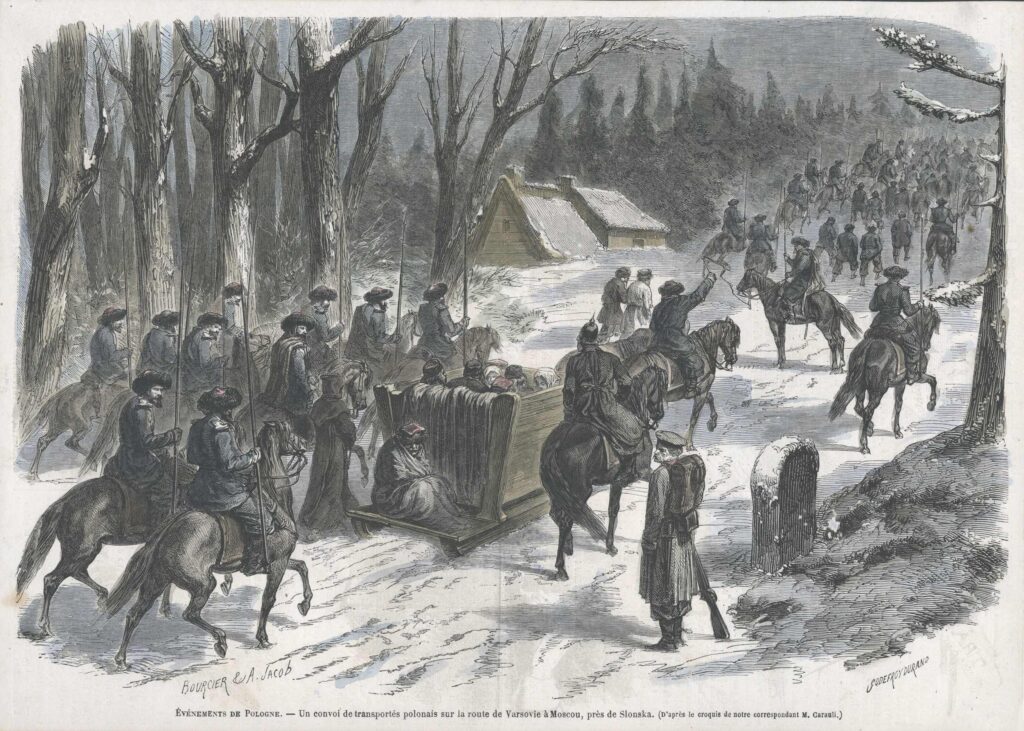

The article describes the conditions of women’s travel and stay in Siberia using the example of Maria Morzycka, who, being a mother of four children, voluntarily went into exile with her husband, who was sentenced by the tsarist authorities for taking part in the January Uprising.

The entire article in Polish here: https://swiatsybiru.pl/pl/marii-obuchowskiej-morzyckiej-podroz-do-syberyjskiej-arkadii/