Tomasz Kizny

From the window of the plane from Moscow to Magadan, Kolyma appears as numerous mountain ranges spreading across the horizon. The first explorer who arrived there was the Polish geologist Jan Czerski, who was sent to Siberia for participation in the January Uprising. By the end of the 1920s, in mountains named after him, gold was found. Thus began the tragedy of Kolyma, the largest Gulag in terms of its forced labour and industrial activity. It operated across an area of 3 million square kilometres, i.e., over 10% of the whole area of the USSR (according to data from 1951). Located thousands of kilometres away from inhabitated land, with temperatures reaching -50°C, Kolyma was the Gulag’s most terrifying place. In 1931–1953 over 800,000 people passed through Kolyma’s forced-labour camps, of which at least 120 thousand died (A.I. Kokurin, J.N. Morukow, red. Stalinskije strojki GUŁAGA 1930–1953, series Rossija XX w. Dokumienty,, Moscow 2005, p. 537).

In the centre of Magadan, I come across a socle with a bust of Eduard Bierzin, the founder of the forced-labour camps complex in Kolyma. The bust is not a relic of the times of Stalin as it was erected in 1988. The hotel is on a street named after him, and from the windows one can see the Mask of Sorrow on the hill – a monument to the victims of Kolyma. At the same place and time, a monument to criminal and a monument to his victims were built – a blunt example of post-Soviet moral schizophrenia. It is pointless though to look for a street named after Varlam Shalamov, the author of Kolyma Tales, one of the most important literary testimonies of the Gulag.

I follow Shalamov’s route 500 kilometres north, to the Dzhelgala valley, where the writer was close to death in forced-labour camp, which he described in a short story called The Green Prosecutor. With the help of the foreman of a still-working gold-bearing outcrop, I found the remains of the old camp with difficulty – the rotting timber of barracks which collapsed a long time ago. It is autumn, there are formations of geese flying away on the sky – silence around.

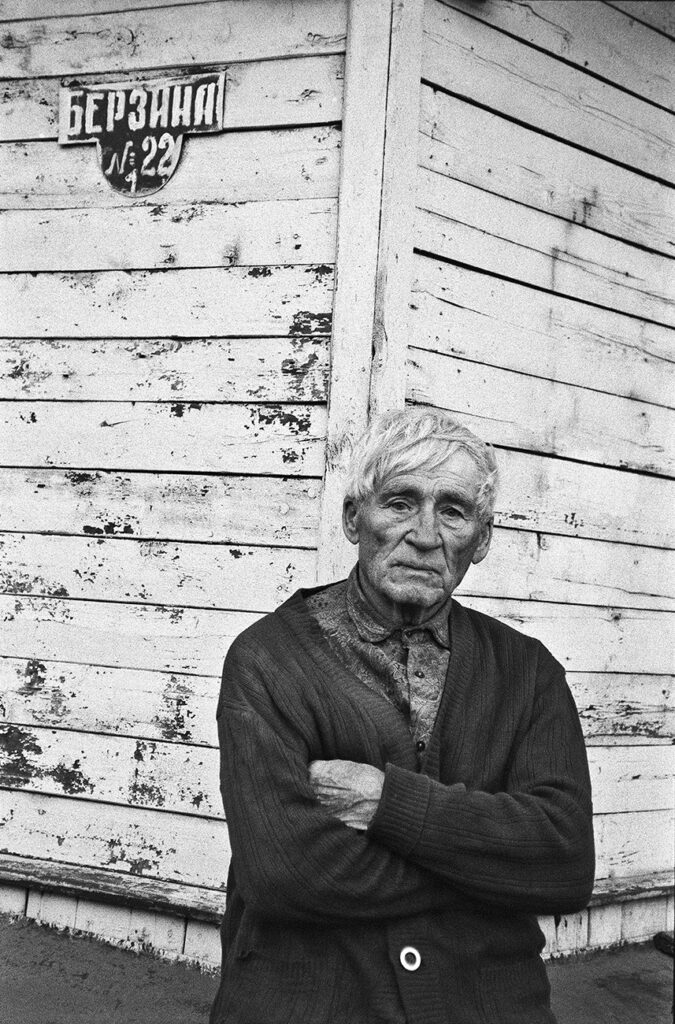

In the nearby Yagodnoye settlement, I visited Władysław Chrystuk, a soldier of Kedyw (a unit of the Polish Underground Home Army) who was arrested by NKVD in 1944 in Lida. During the repatriation of Poles in 1956, he did not receive permission to leave and stayed in Kolyma forever. He worked as a carpenter and lived at 22 Eduard Bierzin Street.

The tin and uranium ore mines in the mountains of Butugychag in Ust’-Omchug region are one of the few places where the remains of the Kolyma forced-labour camps can still be found. The mining area consisted of 6 main camps, many smaller camps, 20 galleries and a uranium enrichment workshop, where unaware prisoners were exposed to radiation. I took a few pictures and quickly left this place. After a long and strenuous walk, I reached the ruins of Sopka forced-labour camp, high in the mountains. “The mortality rate in this camp was the highest. If a friend hadn’t helped transfer me to work in the camp in lower Butugychag, I wouldn’t have survived” – recalled Valery Ladieyshchikov, a prisoner of Butugychag in 1945–1954 (“Magadanskaja Prawda”, [“The Magadnian Truth”, 5–6 November 1991).

The house of the commandant, Maleey, was standing above the camp. Only ruins and a children’s swing on the verge of a terrace remained. It is sunny, and the vast mountain landscape is breathtaking. I imagine a child on the swing and those beyond, emaciated, dying alone in this big, unmoved mountains. As I walk down the valley, I recall the lyrics of a song from labour camps:

[Called a wonderful planet

Oh Kolyma, be cursed

You must go insane here

There is no way back]

Tomasz Kizny is a photographer and journalist, author (in collaboration with Dominique Roynette) of a photo album entitled Gulag, Warsaw 2015

Translated by: Agnieszka Glińska