Interview with Prof. dr hab. Karol Olejnik

In the autumn of 1943, the hastily formed 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Infantry Division suffered its bloody baptism of fire at Lenino. Most of the soldiers who had joined its ranks only a few months prior ended up in the Soviet Union as victims of deportations and labour camps. Fighting under the command of General Zygmunt Berling against the Germans was a chance for them to regain freedom, but they could not have known that the forming army was only a tool in Stalin’s plans regarding post-war Poland. Dr Popławski discusses the circumstances behind the formation of Berling’s Army and the Sybirak elements of this story with Prof. dr hab. Karol Olejnik the eminent historian and researcher of the Polish army.

Piotr Popławski: In 1942, Anders’ Army was evacuated from the Soviet Union. It had been formed on the basis of an agreement between the Polish Government in Exile and the Soviet side. What political forces decided to form more Polish troops in the ‘inhuman land’ in 1943 and why?

Prof. dr hab. Karol Olejnik: Addressing this question requires presentation of a number of both military and political issues. Well, after General Anders’ Army left the Soviet Union for Iran, relations between Moscow and the Polish Government in London changed rapidly. By Soviet propaganda, the Polish Government was formally accused of violating the July/August 1941 agreement, which provided for the participation of the Polish army in the fighting against the Germans alongside the Red Army. In doing so, Moscow ignored the fact that Stalin’s approval of the evacuation of Polish forces to Iran was the result of the efforts of the Brits but instead responded with a series of far-reaching political and administrative decisions. Above all, despite strenuous efforts by the Polish side to further recruit people within the USSR who could join the troops that came under the command of the Western Allies, these requests were rejected. At the same time, the Soviet authorities dissolved all conscription commissions and recruitment centres of the Polish army. Further developments of events must be viewed in the context of developments on the Soviet–German front, which affected Moscow’s political decisions, also regarding the Polish issue.

An analysis of the wartime events leads to the proposition that at the turn of 1942 and 1943, and later in the summer of 1943, the situation on the Soviet–German front distinctly clarified. A few events contributed to this: stopping the Germans near Moscow (December 1941), winning the Battle of Stalingrad (early 1943), and a little later – winning the great Battle of Kursk (summer 1943). Historiography generally accepts that at that time Germany’s offensive powers on the Eastern Front were finally exhausted, and the Soviet side was able to go on the offensive. In the context of political events, all it meant was that Stalin gained the opportunity to factor in favourable developments after further successes by his army, which, advancing westwards, would enter Polish territory. There can be no doubt that the Leninist dream of bringing far-reaching revolutionary social change to the entire European continent (or at least to its central part) had never been forgotten in Moscow. Its hopes were now (having previously defeated Germany) taking shape. That said, the Polish issue came to the fore in multiple contexts.

Moscow had to weigh up both the question of the borders with Poland and the future political shape of our state. After all, the annexation of the eastern territories of the Republic had taken place as a result of the treaties with Hitler, but Moscow did not intend to give them up. What is also worth pointing out is the historical ramifications of past relations between Moscow and Warsaw hanging over all of this. There was, therefore, the problem of the extent to which the future authorities in post-war Poland would be subservient to the expectations of the eastern neighbour. The Polish Government in London could not guarantee anything. As it would soon become clear, Stalin was prepared to do a lot in order to achieve the state of affairs he wanted. The aggravation of relations between the Polish authorities in London and Moscow after the departure of General Anders’ troops did not serve as an excuse for a final severance of relations. After all, both sides formally remained in the camp of the Allies fighting the Germans. It did not become a reality until April 1943 with the revelation of the graves of Katyn, but steps to resolve the issue had already been taken by Stalin.

As a result of the war with Germany, it was not only those Poles deported to the Soviet Union by the governmental authorities for political reasons, but also supporters of the reality that prevailed there. Although the old communists (former activists of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP)) were killed off by the Stalinist purge of the 1930s, in addition to the survivors of this group, there were a few supporters who had escaped from the Nazi occupation. The exiles, civilian and military refugees, together with those taken prisoners by the Red Army after the aggression of 17 September, formed a huge pool of people from which it was possible to select both those already convinced to cooperate and the opportunists willing to do so. The remaining vast majority had one goal in mind: to get out of this ‘paradise’. Stalin’s intention was to create a dependent Poland after the war, but with a semblance of political independence, whose authorities would have a reasonably credible social remit for their activities. And the best way to do so was by creating Polish armed forces from scratch which, after entering the homeland alongside the Red Army, could guarantee the pursuit of Moscow’s goals. With this end in view, it was essential to rely on people from both military and political circles and to entrust them with the completion of the aforementioned tasks. At this point of our pondering, two names appear. The military side was represented by Lieutenant Colonel Zygmunt Berling, while the civilian side was to be carried out by Wanda Wasilewska.

She was the daughter of one of Piłsudski’s closest associates, a pre-war left-wing activist and, at the time of events under discussion here, a staunch communist. Last but not least, she was a member of the All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party. Serving at the front as a Red Army colonel, she had already put forward ideas for a centre to deal with Polish affairs in the Soviet Union and work towards mutual rapprochement. She also advocated the need for Poles to serve in the Red Army, which could not be approved by Moscow due to the already mentioned Allied conditions. However, when the army commanded by General Anders left the USSR, things took a different turn. Wasilewska was called to Moscow, where she worked with Alfred Lamp to refine her plans. As for Lieutenant Colonel Berling, he was the commander of one of the formation centres of General Anders’ Polish Army in the Soviet territories, but he never went to Iran. It remains beyond our consideration whether he did so purely of his own volition or whether it was the result of previous collaboration with the Soviet secret services. The fact was, however, that in the new situation, he was summoned to Moscow, where he drafted a memorandum outlining a plan to create a new Polish army, independent of the Polish Government in London. The Polish people who were in the Soviet Union at that time were expected to serve in it.

Both Wasilewska’s initiative and Berling’s memorandum gained in importance at the beginning of 1943, when there was another friction in relations between Moscow and the Polish Government in London. At that time, the Soviet authorities notified the Polish side that the Poles living in the territories annexed to the USSR in 1939 had become Soviet citizens. This was blatantly contrary to international law and meant that the Polish authorities would lose all control over thousands of their citizens, who could be subjected to Moscow’s numerous legal and administrative decisions, including the obligation to serve in the Red Army. Moreover, this decision meant legitimisation of the change of the Polish–Soviet border. When the Republic’s government opposed these moves and demanded a response from the Western Allies, Stalin saw this as another hostile act and decided to take up the proposals articulated by Wasilewska and Berling.

At the beginning of February 1943, following a conversation with Stalin, Wanda Wasilewska was granted permission to set up an organisation in the USSR known as the Union of Polish Patriots (ZPP – Związek Patriotów Polskich), which was intended to bring together Poles of different political views within its ranks. The purpose of this organisation was to rebuild the Polish state in good allied relations with the USSR after the end of the war. A few days later, Lieutenant Colonel Berling was told by Stalin that he would agree to the formation of the Polish Army, with the understanding, however, that the implementation of this plan was to take place after Moscow broke off contact with the Polish Government. Soon, the Soviet authorities also embarked on so-called ‘passportisation’, which involved invalidating all documents held by Poles on the USSR territory and issued by the Polish authorities. Since the Polish government’s disapproval on this issue did not receive the support of the Western Allies, Stalin took it as proof that the West would not interfere in the Polish–Soviet relations. At the turn of March/April 1943, the Wasilewska/Berling duo had already officially asked Stalin to create a Polish military unit, making the suggestion that its cadre (due to the lack of sufficient numbers of their own) should be the Red Army officers of Polish origin. Waiting for official decisions from the Soviet authorities received an unexpected and tragic boost in mid-April. Indeed, the Germans made an annoucement about the discovery of mass graves of Polish oficers at Katyn. Despite a very even-handed international response from the Polish authorities, Moscow broke off diplomatic relations with the Polish government on 25 April. Polish affairs, including the question of creating armed forces fighting alongside the Red Army, were henceforth solely in Stalin’s hands.

Thus, the formation of yet another (after the Anders’ Army) Polish armed force in the Soviet Union was formally the result of the initiative of a group of Polish communist activists, but in fact, the realisation of Stalin’s far-reaching intentions. The situation on the battlefronts against Germany at the time fully justified plans for the political shape of Europe after the end of hostilities. For Poland to become an amenable neighbour of the Soviet Union to Moscow, Stalin needed both pre-established and subordinated political structures (which the ZPP was to guarantee) and military structures. These were indisputable advantages in the hands of the Soviet dictator in future talks with Western partners about the future of Poland.

With the Polish territories under German occupation at the time, soldiers for the new formation could only be recruited from the Soviet Union. Do we have an estimate of the capacity for mobilisation among the Polish population in the Stalin state?

It seems impossible to give an exact answer. Referring to the total number of Poles in the Soviet territory misses the point, because it would mean including inhabitants of territories seized after 17 September 1939, refugees from lands occupied by the Germans, as well as prisoners of war. There is no accurate data, and estimates have significant discrepancies. However, for the sake of considering the military aspect, we can use the calculations made by General Anders’ staff. They showed that there were enough Poles in the Soviet territories to form an army of around 100,000 soldiers. If we assume that more than 70,000 soldiers left with Anders for Iran, this does not mean that the mobilisation capacity of the forces that Lieutenant Colonel Berling was to form shrank to the remaining 30,000. They were far greater but, as Berling put it in his letter to the Soviet authorities: ‘Due to organisational challenges, it is not feasible to call up these men immediately to the Polish Army. However, in the first instance, it is possible to form one division and its reserve unit’. We should certainly emphasise that the ‘organisational challenges’ put politely by the letter’s author were not only the enormous distances and the lack of a sufficient circulation of information, but also the reluctance of local administrative factors to dispose of their free (often well-qualified) labour force. It was also the hostility towards Poles in general, which was perpetuated by the propaganda after the departure of General Anders’ troops, and finally the extreme physical exhaustion of many exiles or prisoners of labour camps, which made it impossible to take the risk of reaching the places where the army was being formed.

What proportion of the first formed forces were deportees and forced-labourers in the ‘inhuman land’? What were their roles in the forces? Was it anticipated that all positions in the emerging army would be manned by them?

I have not come across a percentage breakdown of these forced labourers and deportees in any of the available literature. But even if there was one, it would bring nothing to the discussion. They were Poles who had been forced out of their lives into this unforgiving land, and who all the same wanted to get out of their predicament.

Why did people who had suffered various forms of Soviet terror decide to join forces under the command of Zygmunt Berling? Was it a free-will process? How was the physical and moral state of Berling’s Army affected by the earlier forced stay of its Polish soldiers in labour camps or exile? How did they deal with the fact that some of the officer cadre was assigned from the Red Army?

There is a present theme in the source literature, in the memoirs in particular, which most generally goes: ‘we failed to join Anders’. And this is profoundly true. For the reasons we have already mentioned (problems with circulating information, vast distances, obstacles from the Soviet authorities, etc.), many of our fellow countrymen fit for military service did not manage to reach the area of the formation of Polish troops. They despaired all the more at the thought of months (years? Perhaps the rest of their lives?) they would endure in the very conditions the Soviets had put them through. No amount of writing is ever able to convey the most imaginative expressions of misery, hunger, cold, the horror of the environment, the hatred of the Soviet authorities, the iniquity of officials, the gratuitous vindictiveness of ordinary Soviet citizens towards the newcomers from distant Polsha (Poland). Altogether, all this added up to the immense suffering of our compatriots. Therefore, what might have been the reaction of these people to the news that here was (once again) a HOPE to get out of this hell? Could there have been any moral or political doubts at the time? That, after all, this is an army organised by people with views that are unequivocally foreign to me, that they are acting with the approval of the man who headed this goddamn machine of oppression? You’ve got to be kidding me!

Political reckoning was made by a small group of people centred around Wanda Wasilewska and Berling. For those who by various means, at the cost of incredible hardship, cunning and bribery, wanted to take advantage of a new opportunity at any cost, nothing was important except one thing: TO MAKE IT. The rest or following days were unimportant. What was going to happen next? Who knew? It was bound to be better than in the current debasement. To make it and become a human being again with the qualities of being truly human. To be around fellow compatriots, to speak your mother tongue, to sing familiar songs, to pray in Polish at evening assemblies, to reminisce and long together for your distant homeland. And what’s more and equally important – to wear a Polish uniform and beat the enemy. The lyrics of a soldier song perfectly reflect this hope: ‘Yesterday a rag, today a coat / Squeeze your belt, it’s time to go!’ That’s right – GO, GET OUT of this hell. So what that there was confrontation with Soviet officers upon arrival where the army was formed? First of all, they wore Polish uniforms. However poor their Polish was, they tried to speak it the best they could (some of them claimed to be Polish). And since our officers were not there (they had left for Iran with Anders), they had no choice but accept the situation. In addition, for those who were more or less familiar with the army (the non-commissioned officers of the pre-war army in particular), a path to rapid promotion was opening up, which was also of great importance.

The Polish troops were deployed at Lenino in a hurry and despite shortcomings in training. Was it a political decision?

In the above-quoted excerpt from Lieutenant Colonel Berling’s letter (dated 8 April 1943), the following comment was made: ‘The deadline of organising the division must be set today, and work must begin immediately in order to overcome the initial difficulties in time and achieve operational readiness before winter’. Thus, even at the stage of preliminary activities, a sense of haste is evident, which used to be linked both to the plans of Polish activists seeking support from Stalin and to the expectations of the latter. The assumption is that the Soviet dictator wanted to have an argument in hand to predetermine his influence on the future shape of post-war Poland during the forthcoming negotiations with the Western leaders. (Such a conference had already been agreed at the time. It took place in Tehran in November/December 1943.) What this argument was supposed to be was the participation of Polish troops alongside the Red Army in the fight against the Germans. On the other hand, Wasilewska and the ZPP activists who supported her gained legitimacy for their participation in the post-war authorities in Warsaw through backing the Polish formations fighting at the front.

The final decision to create the Tadeusz Kościuszko Polish Infantry Division was made on 7 May 1943, and it culminated (in the spring of the following year) in the formation of the 1st Polish Army in the Soviet territory. The forming-up location was set at Seltsy on the Oka River. From the outset, haste and the resulting difficulties hindered organisational processes. Above all, there were material and personnel difficulties: lack of good accommodation, lack of uniforms or means of transport, disrupted means of communication and food problems. It is worth reiterating that the full-time infantry division needed more than 800 officers. (There were less than 200 by mid-July.) The situation was slightly better in terms of the non-commissioned officers: more than 3,000 were required, while 1,350 arrived.In these circumstances, it was necessary to cover the shortage of officers with Soviets, some of whom actually had some connection with Polishness (children or grandchildren of Tsarist deportees). In fact, most of them were Russians, who treated their posting to a Polish division almost as a punishment. Very quickly, the brotherhood of soldiers ascribed them the name of ‘performing the duties of a Pole’ (POP).

The mention of July just now is justified by the fact that the training of the 1st Infantry Division began midway through that month. The preparation programme for operations stipulated that the division should achieve a sufficient degree of operational readiness within three months. This deadline, based on Soviet regulations, was by design aimed at conscripted young men, reasonably physically fit and therefore able to withstand the hardships of training. Meanwhile, in the case of the 1st Polish Division, as it was being formed, the manpower was not only varied in age, but also in rather poor condition. If we add to this the problems caused by the lack of proficiency in Polish among some of the Soviet officers entrusted with training, then these three months proved to be a period far too short for the division to be fully combat-ready. Thus, if the 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Division was caught in the heat of battle despite a glaring inability to meet the basic requirement of adequate combat training (particularly in tactics and gunfire training), it was for political reasons. Namely, pressure from both Stalin and the Polish communists grouped around Wanda Wasilewska.

At this point, it seems necessary to say a few words about Lieutenant Colonel Berling, a professional officer with combat experience. He knew the condition of the Polish troops’ training perfectly well, but he also realised that refusing to take part in combat was out of the question. To make matters worse, on 1 September, Berling and Wasilewska sent a letter to Stalin requesting him to send the Polish division to the front, which, needless to say, the Soviet dictator approved. On 22 September 1943, the 1st Infantry Division set off for Smolensk. Based on Berling’s own account, the Poles were intended to be exploited during the battle for this city, which required special skills in the conditions of fighting in high-density buildings. After he expressed his opinion that ‘the Poles were able to capture Smolensk from the west many times, so they can also do it from the east’, the decision was changed. Apparently, such historical connotations were not desirable at this point, and the 1st Infantry Division was made subordinate to the Soviet 33rd Army operating in an auxiliary line.

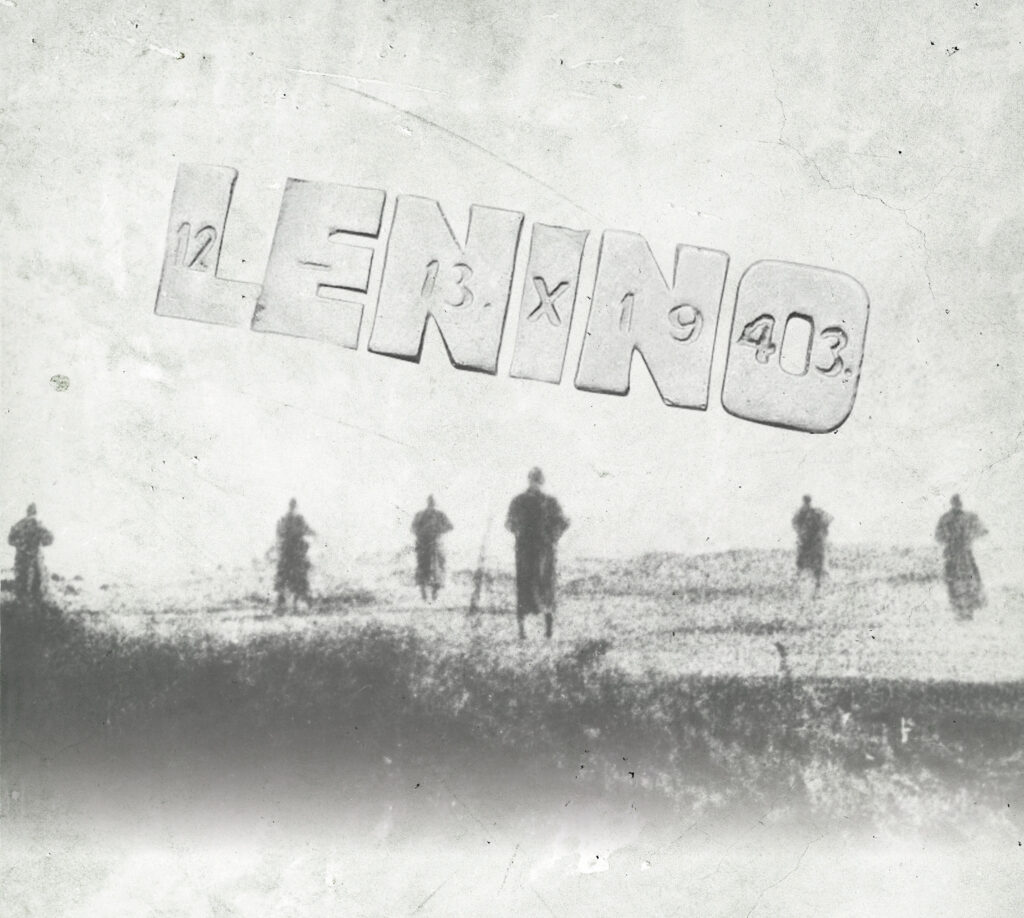

Let’s take a closer look at the Battle of Lenino that took place on 12 and 13 October 1943. What was its course and significance for the situation on the Eastern Front at the time? What accounted for the defeat and the considerable casualties suffered by the Polish army?

The 33rd Army was to break through the German defences (the 39th Panzer Corps was the enemy) and go out to the Dnieper River to capture a crossing on that river. The 1st Infantry Division was to attack in the first echelon in a 2-kilometre-wide section. With the Soviet divisions on its flanks (the 42nd and the 290th Divisions), its task was to break through the first German positions (it was the 337th Infantry Division well armed with heavy weapons and supported by both armoured weapons and the air force) and enable the 5th Mechanised Corps, located behind the aforementioned divisions, to join the combat. However, even during the preparation stage, a series of wrong decisions were made. The 33rd Army commander, lacking adequate intelligence, assumed that the Germans had been defeated and would surrender under firm offensive force. The Soviet divisions in positions on the flanks of the 1st Polish Infantry Division had too few man for the task at hand. Then to make matters worse, the Poles were to carry out the attack in the harsh terrain of the 500-metre-wide swampy valley of the Mereya River. Finally, the assault on enemy positions was to be preceded by a 100-minute Soviet artillery barrage which, as the attacking infantry advanced, was to be moved deeper into enemy territory. Getting ahead of events, we should mention that this element of the plan was not fully implemented either. Previous studies of the battle discussed here have overlooked another important detail that played a role in the course of events. According to Soviet sources, several hours before the attack, 25 soldiers of the 1st Infantry Division crossed over to the enemy side and informed the Germans of the planned attack, as well as of the Poles’ presence. As a result, on the eve of the battle, the German side played The National Anthem of Poland through megaphones and called on the Polish soldiers to come over to their side. As a matter of fact, the Katyn massacre featured in this text as well.

The Polish troops began the battle at dawn on 12 October with an attack by the 1st Infantry Regiment on the front flank of the enemy defence to carry out reconnaissance. But under heavy German defence fire, the attack failed. In this situation, the attackers entrenched themselves and waited for the main assault. Supposedly, it was preceded by the aforementioned artillery barrage. However, it ceased after 40 minutes, which the 33rd Army commander later explained as information about the enemy’s alleged withdrawal from the defence positions! However, the result was tragic for the attackers, as the Germans were not overpowered and were able to make full use of all their means of combat. Despite the change in the execution of artillery preparation, the Soviet commander reiterated the order for the Polish division to assault with its entire forces.

In the first echelon, the 1st and the 2nd Infantry Regiments took the field. The assault in the extended line was staggering. The soldiers marched as if on a drill: even, upright, as if despising death. The first line of enemy trenches was captured, but from then on, tragedy began. The Poles’ dynamic assault left both flanks deprived of cover as neighbouring Soviet divisions fell behind, unable to break through enemy defences. The result was that the German troops’ fire was directed at the Poles from both flanks as well. The Polish divisions captured two villages: Polzukhi and, a little later, Trigubovo (these were the enemy’s most important points of resistance in this section of the battle) and penetrated the German positions to a depth of 3–4 kilometres. But under heavy fire from the counter-attacking Germans supported by air attacks, they had to lag and after a while began to retreat. At this point, there was a clash of forces between the retreating and the attacking Polish units of the second echelon, which had just crossed the Mereya River. Confusion between offensives and retreaters ensued, with losses mounting. The German aerial superiority dominated the battlefield. The Polish infantry fought a fierce battle with the enemy infantry, who sought to regain the lost first line of their resistance. To make matters worse, the swampy river valley prevented our infantry from receiving support from the 1st Tank Regiment. The machines were bogging down in the mud, proving that no proper reconnaissance had been carried out before the battle. Towards the evening, the troops of the first echelon made another attempt to attack, but without making any field gains. Fighting also continued on the night of 12/13 October. It was then possible to move a dozen tanks across the river to support the attack by Polish units. The troops of the first echelon received ammunition and the 2nd Infantry Division managed to capture Polzukhi again for a short period of time. However, they had to retreat under a barrage of machine-gun fire and air attacks. We should mention that Soviet aircraft did not take part in the battle at all. Before noon on 13 October, the Polish division across the entire width of the captured area had to go on the defensive, suffering huge losses in the process. The Soviet units fighting on the flanks of the 1st Infantry Division, despite a clear order from the 33rd Army commander to continue the assault, failed to break through the German defences. In his memoirs (published in Poland at the beginning of the 1990s), General Berling even blames the Soviet divisions for deliberate inaction and calls the commander of the 33rd Army a ‘fool’ or a ‘criminal’. Eventually, on the night of 13/14 October, the Kościuszko troops were loosened up and retreated to the second echelon of the 33rd Army.

In the battle, which, for propaganda reasons, used to be called the Battle of Lenino, losses reached almost 3,000 men: killed in action, wounded and captured or missing. (It was actually the Battle of Mereya or the Battle of Polzukhi, but that would have not had the same overtone as the official name.) It accounted for almost 24% of the 1st Division’s personnel and was the result of the combination of political and military reasons. The former concerned the decision to send the Kościuszko soldiers to the front despite inadequate training. This assault on the German positions in the extended line – as in an drill – was not the result of recklessness but of a lack of habit in moving under enemy fire. As an indication of the political significance of the fighting at Lenino, it is important to note that almost immediately after the battle, a footage report was made, which Stalin later presented to the Western Allies at the Tehran Conference. A whole range of purely military errors were at play. After all, how to treat reducing artillery preparation from 100 to 40 minutes? How to treat the 33rd Soviet Army commander’s order that on the evening of the eve of the battle, the 1st Infantry Division should conduct reconnaissance by combat, thus eliminating the element of surprise? How to treat the lack of reconnaissance of the assault area and the failure to prepare the appropriate means to enable the tanks to cross the swampy valley? How to treat the fact that the Soviet officer in command of the 1st Infantry Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Derks, completely drunk, slept through an assault by his soldiers in a barn and later escaped responsibility by hiding in the headquarters of the 33rd Army? There were shortages of ammunition supplies for the offensive (experienced particularly by the 1st Infantry Regiment), a catastrophic shortage of food for the soldiers remaining in captured positions, poor command resources resulting in loss of contact with the battlefield. Last but not least, there is the more general – but how true – argument: the 1st Infantry Division suffered losses because that is how the Red Army fought. The number of casualties was unimportant. The Soviet high command never used to reckon with this fact, according to the popular adage: ‘We have a lot of people’.

Any losses at Lenino had to be replenished. Besides, Berling’s Army was growing. The ability to recruit soldiers from among the exiles and labour camps was running out, and people from the pre-war Polish lands occupied by the Red Army began to be called up for service. Nevertheless, was there any Sybirak ‘ethos’ in the oldest units of Berling’s Army (the 1st Infantry Division, the 1st Panzer Brigade)? Did the Sybiraks try to stick together?

A precise answer to this question does not seem possible. I am not aware of any specific research. No doubt, those who ‘marched from Lenino’ may have had a sense of community. They must have had a reason to be proud in some way: that they had been fighting from the beginning, etc. In this question, I can sense a trace of memories about ‘The First Cadre Company’. (It was the legionaries that used to sing: ‘And when the uprising happily ends / The First Cadre become the guards’.) However, the scale of events discussed here was different. It was so different from the bunch of soldiers gathered around a charismatic military leader. There, it was the elite of the intelligentsia who fought. Here, it was mostly simple people for whom making it to Poland was the limit of their political imagination. There was no military leader here. Even though Berling dreamt of being one, watchful ‘comrades’ led by indomitable Wanda made sure that the dream ended there. In this regard, one can cite, for example, the criticism of General Berling’s order issued on the eve of the battle. The order referred to the role soldiers would play in Poland in the future. It received a harsh reaction on the pages on the ZPP’s periodical ‘Wolna Polska’ (‘Free Poland’). It was considered distant from communist idealism. In the process, Berling was reproached for, in a way, reaffirming his commitment to the ethos of the ‘legionary clique’ with his order.

Did the Sybiraks stick together? Most probably, as long as it was possible to do so amidst a multi-thousand-strong war machine. They probably did whilst having a drink or two, at their get-together, with fond memories lingering over them like a sleepy nightmare. It probably also took place with promotions. Provided it was possible in the light of the growing presence of the menacing Military Information (as the war continued and the army entered the Polish territory).

Let’s talk more about the way the memory of the Battle of Lenino was treated in the period of ‘people’s’ Poland. Was there time for any information about the participation of Sybiraks in the fighting in the myth of the ‘victorious’ military act of Berling’s Army?

Yes, there was. Memories of someone having had a ‘special experience’ in this otherwise beautiful land (Siberia, that is) are evident in the literature. Let’s not forget though that for the considerable part of the ‘people’s’ Poland’s period, there was a kind of ‘cloak of secrecy’ over the fate of these many thousands of people. Well, yes, they did come to the 1st Division (from exile, mines, camps, etc.). But how they got there was not exactly the matter of discussion. This was sort of understood, but not particularly something to dwell on. In fact, there are several key stages in this regard. Before and after 1956, during the early times of Gomułka and towards the end, when he was geriatric but still watchful. During the times of Gierek? Yes, it was allowed to talk and write about it but in such a way as not to ‘harm alliances’, i.e. indicating that it was a ‘bygone period of errors and distortions’.

Bearing in mind the aforementioned moral dilemmas of the Sybiraks joining Berling’s Army, how should their decision be judged today, in retrospect? In the Sybir Memorial Museum’s permanent exposition, their war effort is presented in a manner comparable to the Anders Army soldiers. Professor, how do you view such a move?

There should be a huge sign on display commemorating the efforts of those who came with the Red Army: THEY WERE POLISH. From Volhynia and Podolia, from Polesia and Vilnius Region, Lviv and Stanisławów, and from many hundreds of towns, villages and small hamlets. They were all POLISH with Polish hearts and ‘Dąbrowski Mazurka’ in their souls. They revered the crowned eagle as a talisman and, whenever they could, they put this symbol of the lost fatherland on their cornet caps instead of the unfortunate kurica (as they derisively called the eagle invented by Wasilewska and Broniewska based on a design from the sarcophagus in the Płock cathedral). In their cantonments, ‘We Are the First Brigade’ was an ever-present song (especially during this first period of army formation in the Soviet land). They felt an unspoken satisfaction when they saw the Virtuti Militari ribbon for 1920 on the general’s uniform. General Sikorski’s death made them cry. General Berling knew their hostile towards the Soviet reality moods perfectly well. As he confessed in his memoirs, he would walk around the camp in Seltsy to eavesdrop on conversations. I find it profoundly unfair that their efforts and blood shed are diminished. Were they to blame for the reality that was established post-1945? To put it somewhat grandiloquently, they were tossed about by the winds of history like so many before them, like those who warred on San Domingo, those who went to Moscow in the ‘year of war’ and fought in the interests of Napoleon, who treated them so meanly afterwards. And weren’t Anders’ soldiers who were even denied participation in the victory parade treated meanly? History must be recorded without sentiment, weighing up judgements and considering all aspects of the historical process. History should teach historical thinking, without the emotional factor, with the national interest as the highest value in the first place. Sadly, this is something our average fellow countrymen have a lot of trouble with. Not for nothing, history was commonly called pulherrima eruditionis pars (the most beautiful part of knowledge). However, it is only the case if we observe all the rules necessary when conducting research.

To conclude with a question about the future: 80 years after the Battle of Lenino, can we say that historians have exhausted and closed the subject? What else remains to be discovered by future generations of researchers?

In my view, the answer is yes, although new questions can always be raised. If the 1st Division and later the Polish Army in the Soviets had not been formed, would Poland not have been what it was post-1945? What role did the cherished in your establishment Sybiraks actually play in the new post-war reality? And straight away another question, this time to all kinds of historical doctrinaires: can they imagine the fate of these people if they had not been given the chance to return to Poland? Of the in-depth issues, one can recall the questions raised earlier about the errors at the Battle of Lenino: what were their causes? Surely, there is going to be a researcher who will be tempted to write new Berling’s biography. But there is one condition behind these (and many other) questions: full access to Russian archives.

A shorter version of this interview was published in the 3rd issue of ‘Zesłaniec’ in September 2023, entitled ‘They were given a chance to return to Poland’.

Translated by Małgorzata Giełzakowska